The book tells the life stories of eight Christians whose lives span over two centuries (from 1707 to 1957): Selina Hastings, Olaudah Equiano, Hannah More, William Wilberforce, Oswald and Biddy Chambers, G. K. Chesterton, and my hero Sayers. All British, they had — Baer argues — over time a massive impact on their culture; as “historian and pilgrim,” he says, he’s “intrigued by the impact of believing people on their neighbors, their nation, and their world” (163). Those influences ranged from the creation of a denomination and a seminary (Hastings) to the education of the poor (More) to a political fight against slavery (Wilberforce) to influential writings promoting Christianity and fighting social evils (Equiano, Sayers, Chesterton, and the Chambers). Baer highlights throughout that it often took them years both to accept Christ’s claim on their lives and then to figure out what it was Christ was calling them to do: “For each of them there were paths taken or experiences undergone or setbacks suffered that could have led to defeat. But these developments bestowed a concentration of courage in the application of their calling to their times — even in the face of blistering criticism — that I, frankly, envy” (165).

I had heard of all of these people before — with the exception of Biddy Chambers (and folks, you need to have heard of Biddy Chambers, because without her none of us would have heard of Oswald Chambers.) I was in fact intimately familiar with the life stories of Chesterton and Sayers. But Baer’s book newly introduced me to the whole life stories of the rest, and reminded me of how crucial Chesterton’s fight against eugenics and Sayers’ emphasis on work with excellence were to who they were as people and as Christians.

Readers of The Well will be particularly interested in the strong women whose stories Baer tells. Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, influenced by the Methodist message, eventually financed or founded over sixty chapels, founded Trevecca College to train her ministers, and — after a crisis with the Church of England in the 1770s — found herself in charge of her own denomination. George Whitefield once remarked that “for a day or two she has five clergymen under her roof, which makes her ladyship look like a good archbishop, with his chaplains around him.” Hannah More wrote influential plays, as well as tracts geared towards the lower-class market, urging moral reform and cautioning against violent revolution. She also educated poor children through a network of sixteen Sunday schools (in the 18th century Sunday schools taught secular subjects to lower-class kids on the one day of the week they had free from work.)

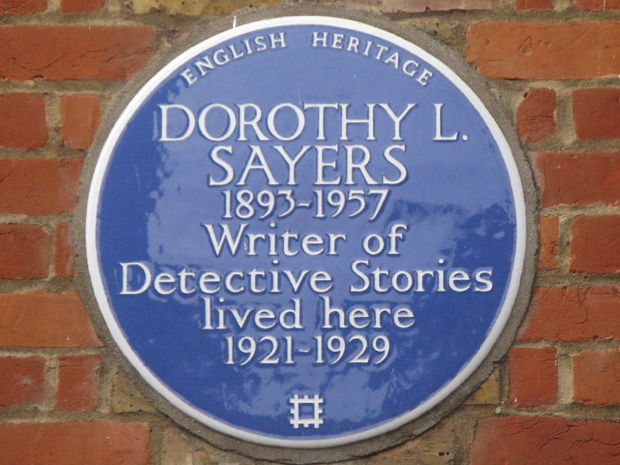

Biddy Chambers, after spending eight years ministering with her husband first to British workers at a Bible Training College and then to soldiers in Egypt, found herself a widow at thirty-three and devoted the rest of her life to transforming the scattered notes of her husband’s lectures into tracts and books that touched millions. (Do you have an underlined copy of My Utmost for His Highest with starred sentences and comments in the margins from graduate school? Yeah, me too. Thank Biddy.) And Sayers, despite the unhappiness of her personal journey, became not only a best-selling mystery author and playwright but one of Britain’s most famous — and wittiest — 20th century lay theologians. (Go read “The Dogma is the Drama” right now, and come back here afterwards.)

I could wish that Baer had not spent quite so long hunting for singular conversion experiences in everyone’s lives: not all of his subjects came to faith in a moment, but their faith was deep and life-abiding all the same. But the book is well worth reading, and even studying in a group; it comes equipped with ready-made discussion questions guaranteed to spark thought. Baer also offers his blog as a place to learn more about and discuss the book.

We may not be called to change culture in the same ways as his subjects (and I question his statement [51], common in evangelical circles, that societal evils can only be combatted by beginning with individual transformation), but we are all called to do it: to speak out against evil and injustice, to seek to bless the lives of those we come in contact with, and to do our work with excellence — even if our work is writing mystery novels. Sayers herself commented in one of those very mystery novels, “We shall know what things are of overmastering importance when they have overmastered us.” This was true of all the Christians whose story Baer tells. His book may help you think about what — or Who — has overmastered you.

See also the review of this book at The Emerging Scholars Network.