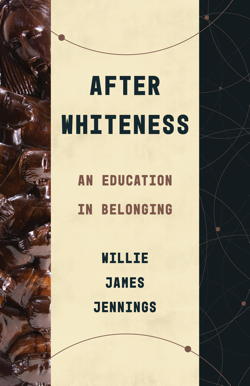

America is in the middle of a racial reckoning. The deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor just over a year ago seemed to awaken the white church to the seriousness of the problem in a way that the long litany of previous injustices in recent years did not. Like many other white Americans, I felt acutely the inadequacy of my own understanding of the ways in which systemic racism operates today. This drew me to read Dr. Willie James Jennings’ After Whiteness: An Education in Belonging. Jennings is associate professor of systematic theology and Africana studies at Yale University Divinity School. He is best known for his award-winning book, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race (2010).

Jennings pulls back the curtain on the subtle but powerful ways that an idea he calls whiteness operates in theological education, which is my career path as well. As Jennings explains it, whiteness is not race or ethnicity, but a way of seeing the world.

Jennings pulls back the curtain on the subtle but powerful ways that an idea he calls whiteness operates in theological education, which is my career path as well. As Jennings explains it, whiteness is not race or ethnicity, but a way of seeing the world.

I ordered Jennings’ book on the recommendation of multiple friends, expecting a treatise with diagnosis of the problem and recommendations for a way forward. Instead, I found it to be personal, poetic, and suggestive rather than prescriptive. At times I strained to see what he was showing me as though looking through a glass darkly – not because his claims were unconvincing, but because the poetic cadence of his reflections danced at the edges on purpose. He explains his use of both poetry and story: "I am engaging in a kind of institutional gnosticism, revealing the hidden meaning in the words, actions, counteractions, and conversations that constitute theological academic life" (25).

Reading Jennings’ work invited me to see academia through different eyes and to imagine a different way of being in the world as a white woman with advanced degrees in biblical studies. As I build a career in theological education, I am realizing how much more learning I have to do. Jennings identifies theological education as the powerful force responsible for shaping western education as a whole. If the western educational project needs a course correction, so does theological education. No matter what your educational context, I commend this book to you, not because I am an expert in the subject, but as one who has been invited into a new way of seeing and belonging.

Let’s explore Jennings’ idea of whiteness. He talks about whiteness not as a person’s skin color, but as a way of being:

It is a way of organizing life with ideas and forming a persona that distorts identity and strangles the possibility of a dense life together. In this regard, my use of the term ‘whiteness’ does not refer to people of European descent but to a way of being in the world and seeing the world that forms cognitive and affective structures able to seduce people into its habitation and its meaning making. (9)

As he sees it, whiteness is a mindset or worldview that prizes autonomy over community and elevates masculinity as the ideal. It’s important to understand that whiteness is not primarily about skin color or gender, but about how we imagine the ideal human. Jennings suggests that the way to reform whiteness is to cultivate belonging. He offers an alternative vision: “The cultivation of belonging should be the goal of all education—not just any kind of belonging, but a profoundly creaturely belonging that performs the returning of the creature to the creator” which in turn fuels our “life together with God” (11). Imagine if our central aim as educators was not simply to transfer knowledge but also to cultivate belonging as we seek to grow in our understanding of God together! Our classrooms would be not just transactional but formational.

With stories drawn from his years of experience as an Academic Dean, Jennings describes the chasm that often separates people of color from fellow students or professors. In order to bridge that chasm, our institutions must reckon with the way our imaginations have been formed by whiteness, leading us to perpetuate colonial ideals. Jennings invites us to envision a different way, a way of belonging to each other, not as purveyors of information but as fellow sojourners.

Schools often make efforts to diversify, but having more people of color on faculty or staff or in the classroom does not automatically resolve the ways that our institutions reward whiteness. For those who are white, like me, it can be difficult to see how institutions that welcome people of color still marginalize them. Without work on our part, we don’t see or feel everything that is seen and felt by our neighbors of color. It takes more than attention, but also deep, trusting relationships. The problem goes much deeper than the makeup of faculties or student bodies, to the ways we are educated and the way our institutions are designed. Jennings calls us to a new way of seeing and feeling with one another that leads us to a new way of education.

This is where Jennings’ reflections are especially helpful. With poetry, personal vignettes, and insightful reflections, Jennings uncovers how whiteness winds its way through the hearts of teachers and students alike, down marble hallways of the administration, through faculty meetings, and into the classroom. At the center of the modern educational project is a stubborn idolatry: the formation of students in our own image — students who read what we read and who write like we write, who have met the same qualifications in the same ways we have. By failing to acknowledge that we still have much to learn, we limit our students’ exposure to other voices. More specifically, Jennings says that the central vision of theological education in North America is to master a certain body of information — information that was produced by white men for white men. He says,

In recent years much has been written about institutions, especially educational institutions and their importance. But those conversations for the most part have been terribly shortsighted, because they have imagined institutions without reckoning with their deep embeddedness in cultivating white self-sufficient masculinity and binding ideas of efficiency and effectiveness to the performance of that persona. (18)

Even when a hiring committee or admissions committee sets out to diversify the faces of the institution, the gravitational pull of this unacknowledged vision forcefully perpetuates ideals that may exclude certain strengths and skills. Everyone, regardless of their racial identity, can be shaped by whiteness.

Reader, as women in the academy, we enter stage left, responding to many of the pressures to perform and conform to the ideal that Jennings identifies. Our dress, our cadence, our style of relating and decision making, our seasons of motherhood and other forms of caregiving, our desire for integration and collaboration rather than isolation and competition — these often feel alien. As those who can often relate to the subtle ways that an institution and its players can fail to create spaces where we can flourish, we are positioned to be allies to others who linger at the edges. White women, like me, might especially act as allies to women of color, who are doubly suspect to colonial ways of thinking. Any of us is well-positioned to make a difference, if we are willing to recognize our power and learn to wield it for the sake of others, at times by giving it up. Jennings has prompted me to undertake the more difficult work of reimagining my own role in education as a professor. I must examine the ways that I am inclined to reserve space at the table for people who look like me and do things my way.

Jennings’ alternative vision is grounded in belonging. He says, “We should work toward a design that aims at an attention that forms deeper habits of attending to one another and to the world around us” (59). That attention to one another can help us with the important work ahead of us.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay.