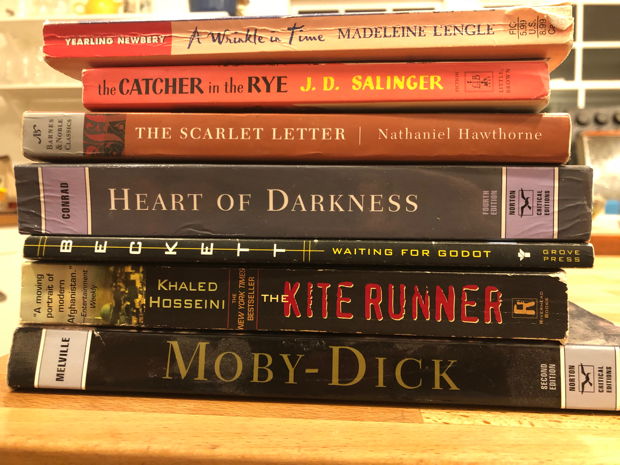

Staring at a computer screen, I played with a phrase for my department’s brochure. I tried “challenging our students’ faith” but worried that parents may misread it as as an intention for students to lose faith. I remembered a nephew at sixteen being given a reading list one summer by his English teacher: all contemporary novels of characters who questioned and left their belief systems. In the end, I settled on “deepening our students’ faith” in hope that the faith of the students in the department grows into a long-term trust in God.

As chair of the English department, I have heard parents’ concerns: fears that the literature required may be “dark” or “anti-Christian” — ultimately fears that their children will stumble in their belief. On a few occasions, my colleagues and I have felt attacked for readings we’ve assigned or texts we’ve published, despite our personal devotion to God’s Word, both Christ and scripture.

An outside organization reported a couple of years ago that the two primary characteristics which distinguished my university’s identity to its members were safe and caring. It’s not hard to conclude that parents send their young adults to be protected from what they’re afraid will erode their children’s faith.

Many of the students who attend my institution enroll in worldview training while in high school. I’m not opposed to these trainings. A goal of our institution is the development of a biblical worldview. But some students seem to leave these earlier educational opportunities with a focus on only criticizing other views, never pointing out what makes common ground. And this approach is a weak spot in their faith. It is based on fear and an assumption that a well-crafted worldview (a mental structure) will be the best protection from loss of faith.

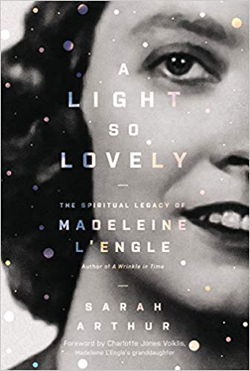

I found the themes of fearful believers and care for college students echoed in A Light So Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy of Madeleine L’Engle. The author Sarah Arthur describes L’Engle, who penned a A Wrinkle in Time, as an apologist. L’Engle drew the “skeptic” and “nominal believer” to Christ, and she confronted conservative Christian college students with a complex God. The goal of both types of apology is a deepened faith. And in particular, the second type of apology is a share of my vocation as a professor at a Christian university.

I found the themes of fearful believers and care for college students echoed in A Light So Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy of Madeleine L’Engle. The author Sarah Arthur describes L’Engle, who penned a A Wrinkle in Time, as an apologist. L’Engle drew the “skeptic” and “nominal believer” to Christ, and she confronted conservative Christian college students with a complex God. The goal of both types of apology is a deepened faith. And in particular, the second type of apology is a share of my vocation as a professor at a Christian university.

The first evangelical college L’Engle, an Episcopalian, visited was Wheaton — and she loved it. She said, “Here at Wheaton, I’m able to be openly a Christian among Christians.” However, as Arthur explains, she was vilified by other Christians who instead of seeing her characters’ reliance on Christian faith (leading to many rejections by major publishers), schemed to ban her books for their so-called “New Ageism.” They called Mrs Whatsit, Mrs Who, and Mrs Which “witches,” although L’Engle labeled them “guardian angels.” These parents who sought to censor L’Engle’s books, although often ill-informed, may have had the same objective as my students’ parents: they wanted to protect young people from the loss of Christian belief.

Two days before classes began, I sat with another colleague in front of an auditorium of first-year students. I made concrete applications for engaging with differing viewpoints in the classroom. “Look for what you have in common first,” I advised, “before you critique.” I tell them I know some of them feel they have to be on the defense. I don’t say it, but that I worry that they’ve been taught to approach material deemed questionable with suspicion only — to never give it a chance to speak to them although its creators were also created in the image of God. I wonder if my counterparts in secular institutions say similar things to students who write off texts viewed as religious.

L’Engle, Arthur informs us, responded to her detractors with a warning in her renowned speech “Do I Dare to Disturb the Universe?”: “We find what we are looking for. If we are looking for life and love and openness and growth, we are likely to find them. If we are looking for witchcraft and evil, we will likely find them, and we may get taken over by them.”

I’m afraid for the students who only critique, find only the bad. I fear that they will have small and pinched spirits which cannot participate in the experience of David in Psalm 18:19: “He brought me out into a spacious place; he rescued me because he delighted in me” (NIV). Although rooted in their mind, their faith’s roots haven’t plunged deeply, with an ache, into their hearts. David exulted in a spacious place after he experienced a hard or uncomfortable place. We need both for faith.

The first descriptor of my institution’s identity was safe, but the second was caring. If we as faculty really care about our students, we will sometimes take them to what Sarah Arthur calls “the hard” or “uncomfortable places,” not only to prepare them for the discomfort they will meet in the world after college but so that their faith will be deepened. Although my department’s faculty avoid engaging with texts regarded controversial in our lower-level courses, our students will encounter some in their upper-level courses.

Christian university students cannot trust only their minds, despite their careful articulation of a worldview. As people living in a world affected by sin, they may have acquired tacit beliefs of which they are not even aware. At the first-year orientation event, I shared, “If something you read makes you angry or uncomfortable, pray about it.” I urged: “Don’t just assume you’re right. There may be more going on than you realize.”

I offered a story of recognizing a racist notion of which I was unconscious upon my first reading of Beloved by Toni Morrison. Realizing that about myself was painful but transformative. My understanding of identity became more complex, and God himself appeared more complex when I contemplated his writing of ethnic diversity into the Gospel’s ongoing story.

As Arthur mulls in regards to L’Engle’s life: “It’s that the uncomfortable places, the troubling questions about faith and Scripture and life and humanity, are exactly where we need to drill down. Focus there, where it bothers you. Dig where it disturbs you, and see what God is doing. Because if God isn’t at work in the hard places—in spite of God’s own people, not just because of them—then why bother with any of it?”

In my colleagues’ and my class discussions and assignments, we provide “on-ramps” and theological “landing pads” for the uncomfortable texts revealing the social realities of God’s beautiful but disappointing creation: humanity. But between the launching and descent, if students stay where they feel safe with a text — if they don’t engage with why they’re uncomfortable — their faith may eventually collapse. No matter how carefully articulated their worldview, they may face a path that leads not into Jesus, but into a nothingness.

“Do I trust the Holy Spirit?” asks Arthur. As apologists, we beg our students to ask the same.