The Word

by Jerusha Matsen Neal

“But Mary treasured up all these things, pondering them in her heart.” Luke 2:19

(Actress sits on a stool, delightedly reading a large book. The book is filled with ribbons, threads and scraps of cloth that serve as bookmarks. She is dressed in simple, non-descript, modern clothing — a turtleneck and slacks, or the like. She is wearing a blue, decorative scarf around her neck, styled in a current fashion. On a table beside her are stacks of books of every kind: science, philosophy, theology, fiction, etc., as well as a cup of tea.)

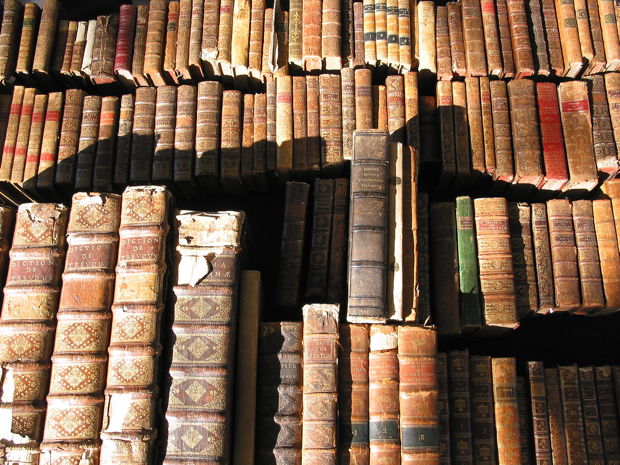

Oh, this is where it gets good . . . (reading aloud — a bit tongue-in-cheek) ‘For it is no true wisdom that you offer your disciples, but only its semblance; for by writing to them . . . without teaching them, you will make them seem to know much, while for the most part they know nothing; and as men filled, not with wisdom, but with the conceit of wisdom, they will be (with emphasis) a burden to their fellows.’ (addresses audience) A bit overharsh, don’t you think? Plato’s Phaedrus . . . (holds up book) discussing the invention of writing — and its danger for humankind. Such cheek. Dismissing all book lovers as a ‘burden to our fellows.’ Perhaps he protests too much — since he is writing his critique of writing in a book! (laughs — pleased with herself) This is why they made me the Divine Keeper of Manuscripts — I’m a regular bookhound. Nobody loves this library more than me. (looking around with genuine delight) You didn’t know the afterlife had a library, did you? I won’t waste my time explaining the metaphysics of it all. Suffice it to say — we have a veritable treasury up here. Our God has always loved the efforts and arts of His creation.

I shouldn’t give Plato such a hard time. He had a love for the “living word” of a really good teacher — as do I. Which raises the question, why would I spend my eternity with books when I could be gazing on the incomparable face of the Word made Flesh? To be fair, I don’t spend all my time here… and “spending time” is a phrase that doesn’t even make sense when there is an infinite amount of time to be had. But the real reason I’m drawn to these stacks of paper and ink is that I’ve always found the Living Word that I love to be tucked into ordinary, material things — like text on a page. These words aren’t dead, as Plato claims; they work on me, making space in my heart for whispers of a Spirit bigger than the words themselves.

It is one of the great joys of heaven that one can pursue the calling for which one was born. I never learned to read on earth, but as George Eliot put it, “It is never too late to be what one might have been.” I think the Church always knew it of me — that I was an undercover scholar… though they never used those words exactly. The medieval painters were constantly painting me with books — even when I was riding the back of a donkey! And now here I sit — glorying in the goodness of God — who lifts up the lowly to know the joys of learning, scholarship… and the written word. Plato took it for granted.

Some say written words make us “forgetful.” Sacrificing true memory for ink-splotched reminders. That’s happened to some, I know. But I can tell you, I’ve been reading for nearly 2000 years, and my memory is fine.

In fact, a good book — or a passage of sweet Scripture — can make the memory live. I remember the light from a star bright enough to make you forget it was shining on the night of a new moon. I remember the smell of animals and campfire smoke. The calluses on my husband’s hand. It remember it was cold. One side of the stable — if you could call it that — was open to the sky. But I wasn’t cold. I suppose it’s hard to get cold in the middle of labor.

(She rouses herself from her memory and picks up her cup of tea; with a smile) This is another great joy of heaven. They allow tea in the library.

You know, there are all sorts of myths about my pregnancy — that I never had a moment’s discomfort. That’s not true. I had morning sickness with the best of them. That’s how I knew I hadn’t dreamt the whole thing up for the first month. But I did have an easy labor. One might even say, a peaceful labor. I don’t mean to disappoint. Mothers almost always wish for those epic labor stories to trade with other woman down the road. You can’t really share “My-labor-was-remarkably-simple” stories. That sort of thing you keep to yourself. But I think, perhaps, when you’ve risked a great deal to carry the Word . . . when you’ve fought to find space to bear the Word, and you’ve endured . . . when the time finally comes to birth the Word . . . you find you have everything you need.

When I look at words on a page, I see the negative imprint of a starry sky. Black stars on a white midnight. It reminds me of that night when I looked up through that gaping hole in the stable wall and watched the heavens dance. The whole world seemed to be vibrating before my eyes. Maybe it was the flicker of the fire outside the door — but I don’t think so. It seemed to me, that night, that every scrap of matter was throbbing with joy — pulsing with sound. It seemed the stars themselves were singing.

Words on a page can do that, too. They can vibrate with song and open up before you like space. They are made of the same stars and dust that made up the Word I held to my breast that night. They’re matter and flesh, nothing more or less. Paper and ink, atoms and elements. If God could find space to dwell in me — why not them?

You know, scientists have studied those atoms and found that they are, in fact, mostly space. (She picks up another book and opens it, proving her point for herself — she knows this by heart, though, she doesn’t need to read it. Soon, she is talking directly to audience) There is in the midst of the seeming emptiness a tiny nucleus. But that nucleus is, in turn, also mostly space. Protons and neutrons spin like stars in its empty sky. But the proton, as well . . . mostly space. Filled with a few baubles and bits like gluons and nuons and quarks. But quarks are also mostly space . . . except — I think they’ve discovered this by now in your time . . . if not, count it a boon for your research — except inside the quark, they have found, at the base of it all, a tiny thread of vibrating energy. And of course, anything that vibrates makes sound.

And so the stars did sing that night — as did those stable walls — my very skin — and these dead words. We sing all of us, creatures of star and stable dust, or . . . more accurately, we are a song. Space and song together. How marvelous when the poet foreshadows science’s discovery, and when a woman like me, who spent so many years spinning thread from a drop spindle, finds that God is a spinner of threads, as well.

(After a pause, she looks down at the book she has been holding) I like to imagine all those threads vibrating together — in you and me — tying our stories into a harmony just out of range of the human ear. Not every thread vibrates with joy, I know (holding up a thread that is serving as bookmark in her book — it is the scarlet piece of yarn cut by the blocked academic in The Annunciation). Not every thread finds a way to amplify its song into the world (holds up a blue ribbon also serving as a bookmark — it is the blue ribbon that belonged to Jeremiah in The Call), at least not in a way in which anyone will ever be aware. But the threads sing all the same.

The threads of a life are precious, and so I save them. (closing her book with deliberate care) Books need bookmarks, after all. I may be the Mother of the Word . . . but I am also a mother of flesh . . . and a loyal friend to those who, like me, bear the Word. So, I pay attention. I collect yarn and ribbons, cloth and cuttings, the threads of human testimony, and I press them between the pages of these books of mine. Between these vibrating black stars of text. (As she speaks, she reveals a bundle of threads rolled in fabric that have been lying on the table among the books. She lifts them to view and places them as bookmarks in the books before her.) I see them. I catalog them. I run them through my fingers like I was spinning them myself. And I whisper over them, “You are not dead . . . just as these written words are not dead. You sing, and I hear the song.”

The world is merciless with matter and flesh. If any would know this, I would know. It pretends to honor it and primp it and coddle it and worship it — but finally, it disdains it. It scorns ordinary things and ordinary people and ordinary words and, all too often . . . extraordinary Ones. It cuts down threads with all the efficiency of a scythe and clears it away as if clutter — making space for the new, the more, the wondrous, the next. It takes a thread and mocks the song it sings, condemns the Word it bears. It takes the Word itself and stretches it upon a cross of fear and calculation. Or worse, it shrugs and turns away. It pronounces the Word dead . . . our song dead.

But by the grace of God, there is another thread . . . a thread that stretches from the highest heaven to the lowest cattle trough . . . to that very cross itself. And this thread, too, vibrates. Sounding forth a note of love from God’s own heart. And that pure note — with purer tone than all our tired cacophony — is the Word made flesh. The Word that is the Christ. And he will not be silenced.

He makes all sing again.

I see your faces . . . your beautiful, ordinary faces. And I know you are my daughters. You lovers of books. You keepers of threads. You bearers of the Word. I tell you a secret. The “space for God” for which you search… is waiting inside you. You were made with galaxies of space in every cell — because the Word — the Living Word — wanted to fill you. (And God knew the Word would need some room.)

The song you want to sing . . . the calling of your heart . . . the song that takes more power than you have, more skill than you possess . . . the song the world has overlooked or buried under mounds of hurt . . . silenced by a cruel cross or simply drowned in noise . . . the song you think you lost . . . That song is humming even now under your skin, in every thread of every cell. And the question comes — to all the words and scraps and flesh of all the world: will you let the Word that is Christ tune your song so that it sings in resonance with the Love of God? Will you let your song be the Word’s song?

If you dare it, it will not matter where the Word is born: a cattle trough, a book, a conversation over tea, a spiral journal filled with chicken scratch, a canvas that is never seen and canvases that are. No matter. The Word will come, and it will be enough. Enough to wake again your wonder for the world — this ordinary, broken, lovely, vibrating world. And you will find, when you have risked it all to carry that Word . . . when you have struggled to find space to bear that Word into the world and have endured . . . when time then comes to birth the Word — you will have everything you need. Space and Song and God who hears. God who speaks through you.

(She closes the book on her lap.)

It is at moments like this, I close my books. Such promise seems too great for human words to bear. They strain under the weight of glory. Plato may have missed the wonder of the written word . . . but he was right about, at least, one thing. There are moments only face-to-face encounters will suffice. Carrying the Word in your belly and holding the baby in your arms are very different things — as related, and yet as different as work from worship. (The following sentence is said with increasing rhythm, as her prose turns into poetry.) No human word has yet been penned that does not pale in beauty to the sound that rises when the threads of our lives sing like strings of praise around the throne of God. No angel harp compares. It is our call — our joy. Selah.

Requests for permission to perform The Word should be directed to Jerusha Matsen Neal through The Well.