She looked at me from across the table and asked, “Have you ever felt as an artist that you really weren’t accepted by the church or the world?” She hesitated. “I mean . . . like both kind of suspect you and you don’t really fit in either world?” I looked over at this young art student and was reminded of my own journey since graduate school to find answers to similar questions.

Where do I fit, both as a Christian and as an artist? How do these two fit together?

When I became a Christian in college, I sat in my studio and wondered at the value of making art in a world that is dying both spiritually and physically. I wanted to invest my life in the things that had meaning. What mattered about that framed image on the wall? It’s a question many artists struggle with inside and outside the church and one we don’t often get help answering from either the broader culture or the church.

On one hand we live in a world that idolizes the “creative” into super-stardom, while at the same time routinely dismissing the ones who don’t make it to center stage. Few of us are able to make a living by art alone and hence are often left questioning our pursuit. At the same time the church looks at art with suspicion and often distaste. Much of what it sees is judged as perverse. Even the best of it is questioned as to its necessity. The church seems to only have room for art in its liturgical form, appropriate for the sanctuary and even then, only in small decorative doses.

So over the years I have challenged God to give me some sense of meaning and affirmation of this “calling”...or…to release me from it. When I look back, I realize I didn’t particularly like this no-man’s land I was living in.

In 1987, while working on a Master’s in Fine Arts, that prayer took me to South Africa. I spent the summer just hanging out. Maybe “hanging out” in a military state locked down in apartheid doesn’t conjure up visions of artistic revelation. For me, though, I was going to the most politically charged place at that time, seeking a different culture from mine and asking God to make sense of the world and my life. Here I am, God. I was more than willing to lay art aside for a feeling of clarity of purpose and meaning.

I spent that summer visiting various ministries and service agencies and asking God if he had anything for me here. I ended up at an orphanage for abused children who had been removed from their homes because of poverty and violence. I had no small epiphany there. At one point the headmistress took me aside and suggested that I might stay and work there with them. As much as that thought excited me, I had no clue what I could offer. I had no expertise in working with traumatized children. I wasn’t a counselor or even an art therapist. They had plenty of people for the laundry or food detail. I felt I was simply a maker of images. What could I possibly do that would be helpful?

She stopped me and said, “You can help children look at clouds and see something more than smoke. You can paint pictures that dream of days beyond fear. You can help children who have lost hope re-imagine it. I can find people to feed these children, but they need so much more than food.”

A tiny light turned on for me. I began contemplating the relationship between hope and imagination. It seems easy in western culture, where we have so many choices, to believe that the arts and this creative thing inside us that fuels the arts is just another choice, another lifestyle. To some it feels elitist, to others superfluous, and to a few of us, we can’t seem to make it through our days without it. But it always feels like a choice and I was struggling with whether it was a worthy enough choice.

But here, where there seemed to be so few choices, here finally, I was beginning to see how essential creativity and the arts were to being human. When we question the value of the imagination and the art it produces and relegate it to a position of simply “wall decoration,” we miss something very essential about God. The God who is Creator has made us in his image to be creative. And it’s in this creativity that hope and faith are fed. This was the beginning of a new theological understanding of art for me.

I didn’t stay in South Africa. Instead I returned to school to finish my degree. In a strange way, that invitation to stay helped me find the reason to go back and to continue to think about what I was doing as an artist.

But Africa wasn’t done with me. It called me again in 2000 and provided another art lesson. Right across the border from South Africa, one of the wealthiest countries on the continent, lies Mozambique, one of the poorest. It is riddled with a history of civil war, natural disasters, and AIDS, leaving many widows and orphans. Still in search of my own direction, I found myself helping at an orphanage in Maputo.

At first I wasn’t sure what I was doing there. I knew I had come hoping to help as well as to discover something about God and myself. Mozambique was another attempt to go to the “ends of the earth.” But I didn’t really have a specific plan. Once there, I wasn’t sure what to do. The missionaries who ran the orphanage simply said that God had brought me there so they felt sure he would show me what he wanted me to do there. This all sounded a little vague to my western, task-oriented self and made me fairly uncomfortable.

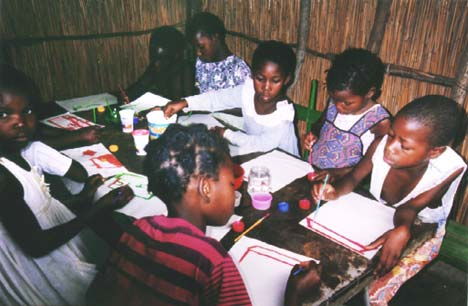

I decided to get into my comfort zone and sat outside my little compound with a pad of paper and pencil and began to draw. Within minutes I was surrounded by a host of tiny, wide-eyed tots chattering in words I couldn’t understand as they watched me work. I began handing out paper and colored pencils to excited little hands and we all drew together, laughing and admiring each other’s creations.

From that moment on, I was followed by a faithful and growing group of budding artists. I felt like a pied piper of sorts. In the mornings I would hear knocks on the lower half of my door, “Mama Rosa will you get up and draw with us today?” I called together impromptu art classes that always brought as many kids as the room would hold. Other times we would sit outside tearing colored paper, gluing, and painting. Our sessions ended with “exhibitions” as we showed each other our creations and took our bows.

Here I received another lesson about creativity and the arts. Here where everything had been stripped down to its basics, where the majority of every day was focused on getting food and water, where housing often meant mud huts with corrugated tin roofs, here where there was little time or energy for extras, here art was still in the mix. It was one of the essentials that remained when many other things fell away. It is essential to our humanity.

I used to believe art was a gift. That is how it was described to me both in the church and in school. It was something special given to certain talented people. I was taught from 1 Corinthians that just like some were given to prophecy, others to teaching, others were given to art. (Of course Scripture doesn’t include art within the specific list but it made sense to me that art would find its place on the list of “gifts” if every gift was listed.)

I don’t believe that anymore. I don’t think art is a gift. I think it is essential to the identity of God. We say all the time that God is creative but I don’t think we understand that creativity is essential to who he is. It’s the first thing God tells us about himself: “In the beginning God created…” Creativity is not optional, it’s a core part of who we are as human beings created in his image. You can take many things away from human beings and we will still find some wall to paint on, some stick to draw in the sand with, some way to tell our stories and relate our dreams.

I didn’t stay in Mozambique, either. I have come to see a different kind of poverty in the U.S. that compels me to continue exploring the arts here in this “end of the world.” I believe that as long as we keep seeing the arts as that added-on luxury of the elite and educated that we will remain confused and impoverished as to who our God is and who we are.

There is a growing and earnest discussion happening in the church today about the re-awakening of the arts. It’s an exciting moment. But I think we will miss the mark if all we do is allow a little more art into our church buildings or have a visual artist paint an illustration during the sermon time, although certainly the church needs to grow in appreciating and valuing creative expression within the sanctuary. And we will still have not understood the power of the arts by simply affirming those who are trying to function as artists in the community and marketplace, although certainly many (including me) would find it refreshing and life-giving to be encouraged and supported as we live out our calling in the larger community.

I believe a true reformation and awakening of the arts within the church depends on our understanding and acknowledging the place creativity has in our definition as human beings created in the image of God. We cannot limit our discussion to how to support artists in the church. We in the arts are only a casualty of a much greater disorder — the poverty of imagination and creativity overall. As we have shut down this understanding of God and ourselves, we have also shut down the voices in our midst who were meant to awaken it and build it up.

In many ways we have forgotten what we might have known as children. Creativity is part of our core created being. And it is through creativity expressed through art that we can begin to re-imagine hope for our time. Maybe this is the greatest value of art today, both inside and outside the church.