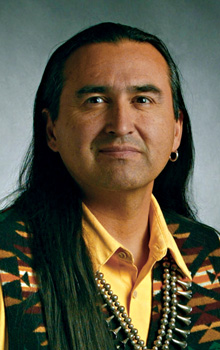

The American Church has a great friend in Dr. Richard Twiss.

Published posthumously, Rescuing the Gospel from the Cowboys could be summed up in the title of the first chapter: "The Creator's Presence Among Native People." Simply, this is what Dr. Twiss begs the American church — and the global church — to recognize: that the God of Israel and Jesus has been, is, and will be working in every human community, creating, saving, speaking, and drawing up out of those communities by the Spirit a love for the Creator and Creator's Son. Our job is to see this and celebrate it.

The problem is, this has not been America's track record. In the first third of his book, Twiss builds a foundation of stories and research, beginning with God's presence with and revelation to Native Americans before the arrival of European traders and missionaries, and ending with the current Native Protestant Christian, and her place in the nation, academy, and church. He builds a history of the Native Church as one in which receiving Christ has meant rejecting tribal identities and practices. To become a branch on the vine of Christ, Indigenous peoples have been historically forced, then forcefully encouraged, to hack away their roots.

Over time, then, even in those who wish to follow Jesus, there remains a deep distrust of one's home culture, which is then replaced by what the White church is offering or insisting upon. Cultural treasures like knowledge traditions, Indigenous music, and languages become lost under complex centuries of subjugation, abuse, and countless other indignities which cannot be disentangled from a Euro-American church and “mission.” This is especially so when this church continues to insist that Native members behave, look, sing, and worship in particular (i.e. White) ways. Life and worship that appear clearly Protestant, Evangelical, and Caucasian are then billed as the "clean" or neutral starting point for worship of God, safe and free from complex Native, "pagan" cultural expressions.

But Twiss reminds us, the White American Evangelical community does not offer a safe cultural clean slate at all. Besides a "clean" or even purely "Christian" culture being impossible, it is theologically erroneous and historically, insidiously forgetful. If First Nations Christian communities must each examine their cultural practices carefully for "other gods," why do American Christians with European heritages not assume they must do this as well? What about being conservative and Anglo makes one exempt from the discernment of "other gods" in one's White, Evangelical cultural expressions of faith and worship? They are there, certainly. And, Twiss exhorts, this forgetfulness and pride masked as humble Evangelical fervor, is one of those gods.

Twiss's book is extremely helpful because it takes this trajectory of Native American interface with Christian Europeans, which has been horrifying and disastrous in countless ways, and presses it into the present, into human stories, and into an excellent question: How do we think about the future of Native communities in light of the love of Jesus, whose name ill-meaning and well-meaning oppressors alike have claimed? Or, as a section heading from Chapter 1 asks, "What happened to the good news?", and what might the Holy Spirit be doing with it today?

In one of the strongest chapters, Twiss imagines a scene in a sweat lodge ceremony, in which several Native Christian men, from different tribes and with different levels of comfort about what they're doing in the lodge, discuss their experience. Much of Twiss's research comes from stories and personal experiences, but it is a complex matter to simply share others' stories, especially stories and experiences of Native peoples, in the form of a body of academic research. So this chapter, in which each character stands as a creative representation of friends Twiss has known and stories he has heard, holds the center of the book in two ways. First, it puts living history, innovation-in-process, and hope for the future into contemporary, detailed, real-life scenarios. We get to watch the realities Twiss describes play out in the bodies and voices of men from various tribes and ecclesial backgrounds, and the result is a spirited, funny, and deeply stirring dialogue about conversion and Native practice. This chapter also moves the rest of the book toward a more thorough examination of what innovative theology and methodology might look like, by offering these stories of experiment and conversion as examples of what has already been happening in Native communities. It's also just fun to read, full of humor and playfulness — crucial parts of any good theological process!

The rest of the book reviews much of the previous material, but with a practical eye for the future of the Church. Though Twiss does not (and will not, as a gesture of respect) describe in great detail practices he celebrates and envisions being more boldly employed in Native Christian communities, he does name examples: sweat lodges; naming ceremonies, Native marriage and rite-of-passage customs, regalia, long hair on men, dances, powwows, Indian songs in Indian languages, ceremonial drums and pipes, and worship with sage, sweetgrass, and eagle feathers. These are all practices that present Native Christians still largely hesitate to embrace as Christ-honoring. On the surface, this might be due to a fear of returning to "pagan" spirits, conjuring powers which are not of God. But held against the experience of the friends Twiss has described, who witness to being profoundly liberated — explicitly, liberated by Jesus — into Native practices, and finding themselves dignified, matured, and pressed deeper into the love of God by these practices, the protest that all wholly Native practices are "demonic" falls short.

Twiss sees here instead the fear of being a self, being a fully inculturated people — this fear being a fallout of European and Euro-American mission, subjugation, and Protestant Evangelical assimilation of Native peoples in the name of Christ. And what lies ahead of the Native Church, Twiss argues, is the creative task of renewal in worship and theology to discover a "positive syncretism" — a way of rethinking the blending of Christian beliefs with Indigenous practices that requires boldness, love, and careful, communal discernment. This exciting, crucial, breathtaking work is not just for the benefit of Native Christians, but for Native communities as a whole. For the Native Church to embrace its identity fully and freely is to release a flow of power and healing into wider communities, to share Christ holistically, by celebrating and offering to the Creator and Creator's purposes the beauty and dignity of an entire people.

Twiss appeals for repentance, justice, and the reimagining of fully liberated Native Christian identities. But he also knows our salvation will not be complete without one another. Twiss is not an exclusivist. He points out repeatedly that a strong Native American community will strengthen Native communities around the world, and that a healthy Indigenous church means a healthy global church. But he also leaves the door wide open for hope in relations between Native and non-Native worshippers of Jesus. Put bluntly, can White people participate in Native renewal? Yes! But not as leaders, only as invited participants. Native communities must have sole responsibility for holding their practices and beliefs up to the light of the Gospel, as an offering, "fragrant and pleasing." Every human community must do this for themselves. The new mission is a gesture of hospitality between Native communities and non-Native Christians, and then it is a gesture of welcome and joy, a gesture that says, not "Come and save us," but Come and see!

As Twiss puts it on the last page:

We must embrace our history...Weep with us and sing with us. The pain will be so deep its only consolation is in our Creator. The great sin against our dignity is answered by a love that brings arrogant violence to its knees. This is the message of the blood of Jesus that speaks better things than that of Abel.

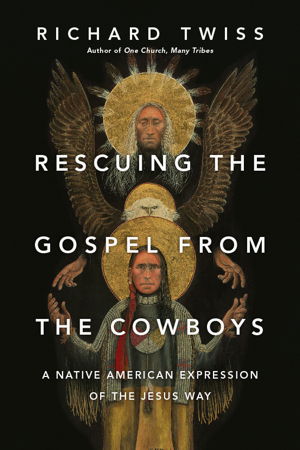

There are sharp words here for the American Church, but in a spirit that is both prophetic and inviting. I have no doubt its release will stimulate the conversation and prayer it calls for. And the cover image, Lakota Trinity, is itself worth the price of the book.