Last Sunday I was sitting in our worship service when my kids began fighting. Again. At that moment, my intense desire was to have complete control, not over myself, but over my children. I wanted the power to force them to obey, to listen, to sit still. My concern was not really about their character or their spiritual development, but about my own performance and pride.

In his new book, Strong and Weak: Embracing a Life of Love, Risk, and True Flourishing, Andy Crouch names my temptation towards authority without vulnerability: exploitation. I may think that it’d be easier to have authority over my children without the risk of embarrassment, but that way does not lead to flourishing — theirs or mine.

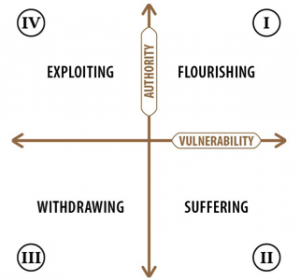

The premise of Crouch’s book is simple: despite our temptation to view strength and weakness as mutually exclusive, we need both in order to flourish. To put it more strongly, Crouch argues that “[m]uch of the dysfunction of our lives comes from oscillating along the lines of false choice, never seeing that there might be another way” (18). Instead of viewing strength and weakness, or authority and vulnerability, along a horizontal spectrum, Crouch plots them on an X-Y axis, forming a two-by-two chart with four quadrants. Each quadrant represents a different combination of authority and vulnerability, and Crouch spends the first half of this short book describing the experiences found in each quadrant: flourishing, suffering, withdrawing, and exploiting.

- Flourishing happens when humans experience authority (“capacity for meaningful action”) and vulnerability (“exposure to meaningful risk”). To be flourishing is to be living the abundant life that humans, as God’s image-bearers, were made for.

- Without authority, vulnerability leads to suffering. Because individuals cannot act to change the circumstances that make them vulnerable, suffering is their story.

- When individuals or communities lack both authority and vulnerability, they exist in the quadrant of withdrawing. Here is the space of apathy and safety, without suffering but also without joy.

- And finally, the one I mentioned before: authority without vulnerability, or exploitation. A person in this quadrant doesn’t experience risk but instead controls others, and the lopsided power of the one leads to the suffering of those underneath.

In the second half of the book, Crouch reminds us that growth is not as simple as just moving “up and to the right.” Flourishing doesn’t always look like equal amounts of vulnerability and authority. In fact, our own individual authority and vulnerability is related to that of the community we serve. He claims that leadership requires hidden vulnerability: to the crowd, leaders seem to have more authority and less vulnerability than they really have. His story of a CEO keeping the company’s precarious position to himself instead of unloading on the employees is a helpful, concrete example of what this hidden vulnerability looks like and why it’s necessary. Crouch maintains that hiding individual vulnerability as a leader is a way of loving a community who lacks the authority to act even if the risks were known.

But there are times when exposing one’s vulnerability benefits the community in a unique way. I think about Santa Ono, President of the University of Cincinnati and InterVarsity board member, who recently revealed his prior suicide attempts. He describes feeling a burden lifted when he went public, but he did not reveal his pain for his own benefit — he did it to help students currently suffering and to reduce the stigma surrounding mental illness:

“I wouldn’t have spoken about this earlier in my life. The reason I can do so now is that I’m speaking from a position of strength. I have demonstrated that not only am I fully functioning, but I can really thrive in my current position. If anyone can speak about struggles, it should be someone like myself who is coming from a position of strength.”

Ono’s admission of past suffering serves others in a way that announcing a current suicide risk would not. His acknowledgment of vulnerability is a way to promote flourishing among those who are yet suffering.

As I consider how to grow as a leader in both authority and vulnerability, it seems messy. How much vulnerability we show to others and for what purpose isn’t something that fits neatly in the two-by-two chart. Yet, Crouch reminds us that Jesus is our example of flourishing in both strength and weakness and that it is Jesus who enables us to act meaningfully and to embrace risk. I appreciate this framework about flourishing — the four quadrants are easy to understand and are persuasive tools for thinking about strength and weakness. And the nuances of how we combine authority and vulnerability, discussed in the second half of the book, have given me questions to consider, points to ponder, and prayers to pursue. This Sunday as I worship with my kids, I want to accept the vulnerability that comes with not knowing how they will behave. And I’m praying for flourishing — that my desire would be to meet God, not to measure up to others’ expectations.