“[A]s we progress in this way of life and in faith, we shall run on the path of God’s commandments, our hearts overflowing with the inexpressible delight of love.”

—Prologue, The Rule of Benedict

The low, dull roar of an industrial fan in concert with the higher-pitched hum of the wet-dry vac in my office drew my heart’s easily preoccupied ear to God’s ever underlying, eloquent silence and had me contemplating the power of water.

Stopping in puddles in front of my open office door, I saw, thankfully, that my books weren’t wet, only my floor. And I was grateful for the help of facilities staff who’d arrived before I could; Bob was there and also Joey, suctioning up the water that had darkened my carpet from sky to navy blue. A pipe in the classroom beside my office had frozen like so many others during the first polar vortex that painfully gripped the unprepared South. The result was a burst pipe and, as we welcomed the thawing process, water spilling into the classroom below.

The water bursting from the pipe had taken out several ceiling tiles, then flooded that second-floor classroom, spilled out through the door, and streamed into the hallway and down the stairs, creating a little lake in the landing between the first and second floors, but only after coursing into my locked office on its way down.

And now I saw that everything on the left-hand side had been moved, except the thank-goodness-still-dry-on-the-shelves books, as if a colossal hand had tilted the room until filing cabinets, tables, trash can, framed pictures, shiny Sutton Hoo helmet replica (from eBay for twenty-seven bucks), and piles of student work had slid over into a careful jumble on the right. But I knew that actually it was the hard work of Bob and Joey, who did me a kindness by shifting everything over so that no more damage could be done.

I stood there, thanking them both, cherishing my books more than ever, thinking how they were gathered over decades, and realizing I couldn’t have possibly replaced them: a ten-pound American Heritage Dictionary and a stout Webster’s Third New International, treasured linguistic tomes, a shelf of Ann Ulanov’s wise works, my library of medieval women mystics, books friends have written, scribbled-in grad school textbooks, Bibles, books by C. S. Lewis, Rilke, Simone Weil, Maya Angelou, Mary Oliver, Lucille Clifton, Emily Dickinson, Carol Ann Duffy (who all feel like friends), plus a dog-eared devotional by Oswald Chambers that was given to me in college. I reflected on the truth that had the ruptured pipe ruined them all, the only volumes that would have survived would have been the ones I’ve given away over the years.

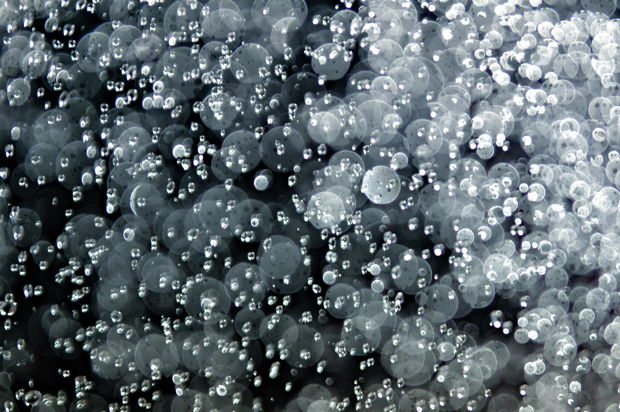

I began considering all that has been written through the centuries using water as a powerful spiritual symbol.

I thought first about the verse in the Old Testament, Amos 5:24, comparing right action to the strength of a great river, an image forever married in our minds with Martin Luther King’s arresting “I Have a Dream” speech,” in which he declaimed racism’s “unspeakable horrors” that “stripped [children] of their self-hood,” and then powerfully declared their dignity by asserting that “we will not be satisfied until ‘justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.’”

And I thought how Christ compares our friendship with him to an unending, inmost-thirst-quenching spring: “[T]hose who drink of the water I will give them will never be thirsty. The water I will give will become in them a spring of water gushing up to eternal life” (John 4:14).

I thought how in God’s blessing on Israel, Isaiah compares the outpouring of the Holy Spirit on God’s followers to life-making rain on parched ground and rivers running througharid earth: “Do not fear, . . . [f]or I will pour water on the thirsty land, and streams on the dry ground; I will pour my spirit on your descendants, and my blessing on your offspring” (44:3).

Hildegard names this divine, animating strength viriditas, repurposing the Latin word for “greenness” for the Holy Spirit’s energy that can “curl clouds, whirl winds, / send rain on rocks, sing in creeks, / and turn the lush earth green.” (pp 18, 37) She sees the Holy Spirit flowing through the universe, charging it with God’s vitality, goodness, love, beauty, and renewal.

Hildegard would’ve agreed with ancient Chinese philosopher Mencius, who described water’s intense persistence as “such that it does not move on until all the hollows in its course have been filled.”(p. 149) I was likewise mindful, in my cold, muddy shoes, that Christ’s loving friendship never falters. He’s ever present to help with each life lesson, frightening situation, daily task, and unknown future.

And I thanked God for moving, like water, through small openings — finding the tiniest of crevices in the walls of ignorance, grief, weakness, and the many different kinds of pain that barricade our hearts — and for offering us his companionship there. I thanked him, too, for the everyday kindnesses and small blessings that possess enormous significance for our souls — like friends who help with flood floors and for the joy of dry books.