Ebola. The headlines began with updates on the spread of the virus in Liberia, Sierre Leone, and Guinea, then the report of an American doctor and nurse falling ill and their arrival on US soil, Liberia has now declared a state of emergency. Kenya has issued travel bans. The virus has traveled to Nigeria. The World Health Organization has declared Ebola an international health emergency. This weekend, residents of the Liberian capital’s largest slum raided a quarantine center for patients and took infected items.

So what do I do with Ebola?

Ebola in Gabon

In 1994 my husband and I moved to Gabon to do student ministry through InterVarsity. Gabon is a small African country, about the size of Colorado, with the Atlantic Ocean as its western border. The population then was around a million, smaller than Philadelphia, Dallas, or San Diego.

In 1994 people fell ill and died deep in rain forest gold-mining camps, far from the capital city of Libreville, where we lived. It wasn’t identified as Ebola until later, and I doubt that it made it into the American news cycle of the time. This was before laptops, when I was getting information on Gabon from books and new friends instead of Google searches and newsfeeds.

The next outbreak occurred in 1996 when hunters came across a dead chimpanzee in the forest. In a place where bush meat is prized, this was a lucky find. Many helped to butcher and prepare the meat; they fell ill with Ebola as well. But still, the outbreak occurred far from our home in the capital, Libreville. It became common knowledge that dead primates in the forest were potentially dangerous. There was no cause for alarm.

The 1997 outbreak hit closer to home. The first death was a hunter in a logging camp. The outbreak was contained until a Libreville doctor contracted the virus and got on a plane to South Africa for treatment. There, he infected a nurse who fell ill and died. The international community paid attention this time. Gabon made the news cycle.

The situation worsened as three people in Libreville fell ill and died after attending a family funeral in a village. This was more serious and hit closer to home. Before this outbreak I had explained to my concerned mom that the virus was far off, in distant villages, that I had no contact with dead primates or the bodies of the victims. I explained that we were in no danger; there was no cause for concern. Now Ebola was in my city. This was different, harder to explain away.

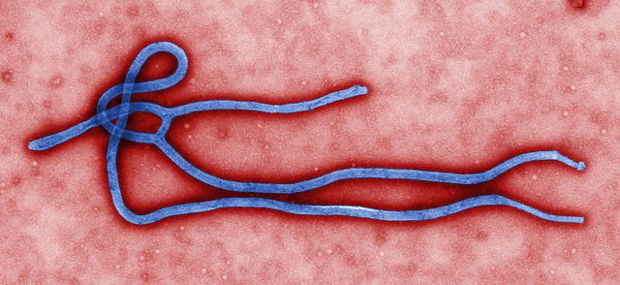

There were meetings within the expatriate community at the time. There were explanations of the means of transmission, with reassurances that this was not an airborne virus. People in the know explained that Ebola wasn’t something you were likely to catch, like a cold. But I think everyone, Gabonese or expat, was a little uptight in those months. We shook hands at church a little less, worried more when we heard a cough in the crowded vans that served as taxibuses. We regarded the sick with suspicion.

We adopted our son in 1999. I didn’t worry about Ebola, and explained again to concerned family that our baby was safe, that we weren’t taking unnecessary risks by living in a place where Ebola seemed to lay dormant. Fears in the city faded as time passed. Colds and flus returned to their commonplace status, no longer cause for alarm.

The last time Ebola hit Gabon was in October of 2001, as our son toddled around our apartment and we prepared for a year’s sabbatical in the US. Again, a hunter in a forest camp fell ill and died. There was close contact, too close, and others in his community fell ill. An infected dead chimpanzee was found in the forest. By the time we were in the US, sending off documentation for our next adoption, the outbreak had run its course.

My American Backyard

So, what do I do with Ebola? I see fear when I check #ebolaoutbreak on Twitter. I see it veiled behind the headlines. It seems we move from compassion and concern to fear all too quickly. We worry about our safety more than we pray for those face to face with peril.

I’m humbled by African health workers who put themselves in harm’s way to serve the sick and dying. Many are poorly prepared and ill-equipped to deal with this virus. I pray that more help and resources from the international community will lessen the burden on workers who are caring for more patients than they can handle.

I know that the early church grew partly because of how they cared for the sick and dying. In The Rise of Christianity: How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Movement Became the Dominant Religious Force in the Western World in a Few Centuries, Rodney Stark explains that the love and care early Christians showed for others contributed to the dramatic rise of Christian. When plagues struck, early Christians stayed in cities to care for the sick and dying.

But the reality of how the Ebola virus spreads and the need for limiting contact with the sick make caring for them particularly challenging. Isolation is necessary even as they need care. I cannot imagine the suffering that the sick and their family and friends are enduring. There can be no holding of hands, no good-bye embrace. Funeral traditions cannot be followed as bodies must be disposed of, away from any possibility of physical contact. Grieving a sudden death is a long process. These added realities will add to the emotional and spiritual trauma that communities are going through.

So what do I do with Ebola? I will follow the news and stay aware of any ways that I can help practically with organizations serving Ebola victims and their communities. I pray that the outbreak will be contained. I pray for the efforts of the international community as resources and personnel are sent. I pray for the safety of the health care workers, that protective measures would be effective as they care for the sick and dying. And I pray for those affected, for their communities. Even after the virus burns itself out, there will be deep scars. We, the church, will need to be there, present, walking alongside survivors in the aftermath.