We introduced ourselves around the table at an InterVarsity faculty lunch. When I described my work with grad and faculty women, one of the men, new to the group, lit up. In a few words Nick Balster expressed his concern for grad and postdoc women in the sciences trying to complete their programs once they had children. He described the modifications he had made to his teaching lab so that women in his research group could remain active and engaged once their children were born. I was intrigued.

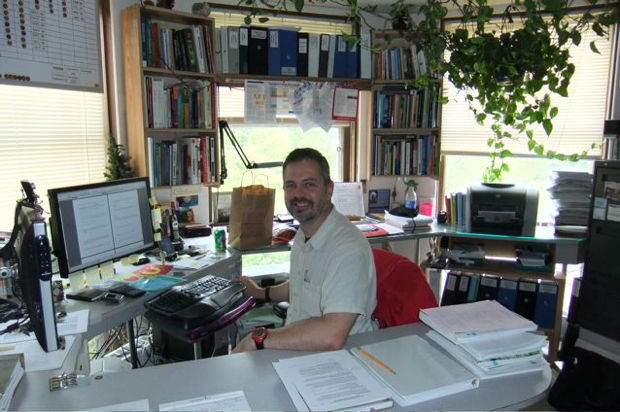

As he was in the final days of his tenure review process, it was several weeks before we could talk again. A soil scientist, Balster is based in historic King Hall, a stone and brick structure overlooking Lake Mendota. I navigated through hallways and up flights of stairs, then down a half stairway to reach his third floor office. Filled with an academic’s requisite books, papers, and electronics, the office still manages to convey a sense of quiet and peace with its stone-encased bay window looking out through a mature canopy onto the lake. The office surfaces were full but neatly kept and I was greeted by Balster’s warm smile and handshake.

Balster came to UW-Madison in 2000 after completing his PhD at the University of Idaho. Before completing his degree, Nick had supported his wife through her own doctorate, into faculty positions, and then as she went through her own tenure process at UW-Madison. So besides a personal conviction to help women and minorities succeed in the sciences, he had observed very closely the challenges a woman (his wife) faced as a graduate student and faculty member.

Balster came to UW-Madison in 2000 after completing his PhD at the University of Idaho. Before completing his degree, Nick had supported his wife through her own doctorate, into faculty positions, and then as she went through her own tenure process at UW-Madison. So besides a personal conviction to help women and minorities succeed in the sciences, he had observed very closely the challenges a woman (his wife) faced as a graduate student and faculty member.

Even so, it was not until Balster was setting up his own lab and his first grad students, almost all women, began to have children, that he became fully aware of what it would take from the professorial side to support these women through their graduate work. He explains, “I had these women, all fairly young, all married, and one already with two kids. I just kind of took them on, naively, even though in my own life my wife and I have been trying to balance work and family all these years — and it hasn’t been easy.”

The first hint that things were going to be different was when his first PhD student had a baby and had to go off her grant. “That’s when the light went on for me,” Balster said, wondering if all of the work she’d put into research and into her own degree would be lost. “I realized I would have to make some changes to support her and the other women working on their research in my lab. I began to really understand what that would mean. I would have to redo my lab. I would have to rethink how we did things like, for example, field work.”

Balster began investigating what was in place at the university to support women graduate students so they could stay in their programs even as they, in their prime child-bearing years, began families. His search brought him to many helpful websites within the university — websites for women scientists, websites for support groups, links to daycares. He joined the board of the UW System Women and Science Program designed “to attract and retain more women and minority students in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) by promoting systematic changes in the ways that science and science education are regarded and carried out within the University of Wisconsin System, the Wisconsin community and beyond.” But what he didn’t find was any hardcore policy or set of procedures.

“This is when I started raising these issues,” he said. “We can’t expect women grad students to go along, have a baby, and be here again the next week to continue their research. I’ve always been pro-family. It not only has to do with my ethics, but with my beliefs and what I think is important in life. I have personally found that if you have a healthy family life, and you’re promoting that in the workplace, work is going to turn out better for everyone and be more fulfilling. So basically, I tried to find resources even though they were very small — $500 here and there — to help these students. But still, there was no policy.”

Researching how a policy might be put in place, Balster realized it was going to take a long, long time for changes to be institutionalized. “By the time I would have a policy in place for my own grad students, their kids would be in high school,” he said. “That’s when I decided to set up conditions in my lab to be as friendly to the mothers as they could be — within my sphere of influence — so the students can still be connected and engaged in their work without sacrificing family. Even if they’re here while breastfeeding, they are still engaged in the research setting. If we can make it possible for them to come in for a lab meeting, we can keep the learning curve from being too steep when they fully engage in their research again.”

We moved out of his office, up the stairs and down the hallway into the teaching lab. Though filled with desks, books, sinks, and cupboards, the space is open and the desks are positioned so that within a quarter-turn, people can see each other. Eschewing the philosophy of isolated study carrels, Balster believes the lab is healthier and more productive when personal interaction occurs and community is reinforced.

In the far corner, partitioned off from the rest of the room, is what one student affectionately called the “lactation lounge.” An inviting retreat, it features furniture selected by students from Pier One — a brightly upholstered papasan chair and stool set, a matching rattan chair, and a rug softening the space and setting it apart from the more businesslike character of the lab. A small chest of drawers is topped with a desk lamp and a tiny toy truck, hinting at smaller visitors.

In the far corner, partitioned off from the rest of the room, is what one student affectionately called the “lactation lounge.” An inviting retreat, it features furniture selected by students from Pier One — a brightly upholstered papasan chair and stool set, a matching rattan chair, and a rug softening the space and setting it apart from the more businesslike character of the lab. A small chest of drawers is topped with a desk lamp and a tiny toy truck, hinting at smaller visitors.

This is a lounge, but not an escape. The partition divider is wallpapered with a map of Wisconsin soils and the electric breast pump and portable crib share space with soil science journals and a bulletin board posting university news. “It’s a nice place for people to come and sit.” Balster says, “Sometimes they just sit here and work on laptops with their child in the crib or sleeping in their arms.” And it doesn’t just benefit women; a male graduate student brings his baby in, too. Besides making it a welcoming space, Balster has taken care to remove all chemicals and other potential laboratory-related dangers from the room.

This works, in part, because much of the actual research work takes place literally “in the field.” “In the field it’s more we’ve just figured out how to make do,” Balster says. “My student who recently had her baby has been terrific about figuring out how to handle it. She’s had my portable crib out on sites. We’ve also had kids out in the field playing in the grass while we worked. They were close by where we could keep an eye on them. We’ve even had grandparents helping out, which I always welcome. Whatever gets the work done, but keeps the group focused. It really comes down to thinking and treating the group as a family. That is the choice I’ve made. I understand and respect that not everyone would agree with that choice. The core goal is to try to work as a family, balanced with the rigor of the research mentor relationship.”

We left the lab and stepped down the half flight into his office. Balster described more of his experience. Although his students seem to be thriving with the adjustments he has instituted, he is frustrated that students cannot count on this level of support throughout the university.

“I’ve never had anyone drop out of my program. Most of my colleagues have had students who have dropped out and I often wonder if it is because the students can’t balance work and home or if they have no one to talk to about how to manage the imbalances of family and graduate school. And further, if they drop out for a time due to family issues and then want to return, they often lose their funding. We’ve got to change these things no matter how seldom they occur to retain women and minorities in academia.

“I’ve had many graduate students in my office telling me things they are scared to tell their major professors who they think just focus on their productivity in the lab and would view family concerns as a weakness. I’m on a committee of a young woman graduate student right now who is pregnant and terrified to tell her major professor. She knew what I was doing in my lab through word of mouth, and so was willing to approach me. I sent her a bunch of resources I knew about on campus. But I had to be frank with her that there is no set policy. There is language that sort of looks like policy, but no procedure that says you have a baby and then this and this and this happens automatically with your graduate program and funding.”

Balster recognizes his mentoring approach has its own challenges. “I’m not saying my model for mentoring graduate students is easy,” he acknowledges. “It’s not. Some days it seems like we’re always talking about schedules. And it’s not only about childcare, it’s families wanting to take vacations or visit extended family, families going through issues in their marriage, families with kids in trouble, families with home or car issues. Do I say to them that I don’t care about what’s going on, just get that publication done, or do I say, how can I help you, so that I can mentor scientists in managing the imbalance between family and work? What resources can I help you with? The way I view it, when there are problems at home, they are not focusing on work anyway, even if they are at their desks. When they’re here, I want their focus to be on work without big worries about home. The more little ways I can help them find a balance, the more they can do their work productively when they’re here. Because at the end of the day I’ve got to be sure that we’re producing, but that I am also building healthy, well-rounded people.

“You can look at it like I’m going to have a lab where students are producing and producing and I’m getting a lot of publications and recognition out of it. Or you can make the choice to say, I may not have a lab that produces like crazy, but I am going to build whole people who can contribute in a healthy way to society.

“I want to let women know that they can have careers in science, while maintaining healthy families. I believe this world, and science, will be better because of it.”

We shook hands and I thanked him for his time and for his work. Realizing the specific modifications Balster has made to his lab may not be viable or necessary for every discipline, I believe his philosophy of support for women in the sciences deserves to be considered by any faculty member. I left the office grateful for his presence on the University of Wisconsin campus, faithfully doing science while faithfully building whole persons.

I am pleased to report that Nick Balster was promoted to Associate Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in July, 2010.