I read the email on my phone in a coffee shop. I sat there with my hand on my forehead to hide my face, my tears dripping onto the table, hoping no one I knew would recognize me.

“I regret to inform you” began the email, like so many emails graduate students receive. My latest application for funding had been declined.

In the documents that accompanied the email, I discovered I came within a hair’s breadth of receiving the award. This was the second time I had applied for the grant, and I’d come nearly as close the year before. The review materials were filled with positive comments, ranking me in the top five of 126 applicants for the grant. And still no money, and no line item on future CVs.

In the week that followed, I went through fieldwork in a daze, my soul reeling as I soaked in the message that yet another committee of “the powers that be” had deemed my research not worth paying for. In that week I felt the temptation creeping up every morning to stay in bed a little longer, to take shortcuts on this research that I was now paying for fully out of pocket. I found snarky sarcastic comments leaking out of my mouth about the review committee’s ineptitude or about my worthlessness as someone now working for no pay.

Rejections are intrinsic to the graduate student experience: funding proposals, job applications, awards, schools. We watch weeks of preparation time, hopes, plans, and thousands of dollars slip through our fingers. How we deal with these rejections will shape our academic careers. We can let them get the best of us, embittering us or becoming an excuse to give less than our best efforts to our research. Or we can use rejections as an excuse to refine our priorities and reexamine what it means to exist in the competitive world of academia. In choosing the latter, I learned two things.

They may control your purse strings but they don’t control you

Having my proposal turned down meant I was not locked into the words I had typed on a grant proposal seven months earlier. I was literally freed (within the bounds of my advisor’s approval) to reconsider what I wanted from my remaining half year of fieldwork. More importantly, this offered a deeper reminder that we should never be fully controlled by the committees that evaluate our work’s merit or the money that supports it. We work for a higher purpose, and those committees and moneys are there to help steer us toward that purpose, not to become the purpose.

For many graduate students, lack of funding means waiting months or years for a chance to proceed. I was fortunate to have a husband with an income allowing me to continue. Even for those whose graduate work grinds to a halt, time waiting can mean opportunities to try other work or pursue classes you wouldn’t otherwise make time for.

Whether funded or unfunded, we had better believe in the research to which we devote these years of our lives. That research had better be something of a gift that is valuable to the world. It had better speak truth to the best of our ability. It had better emerge from the heart of who we are and what we are created to be. Our research had better be of a quality that will — at least sometimes — earn recognition and funding. But not always. Our job is to keep going with the same excellence, whichever the case may be.

Not winning everything is a gift of guidance

In high school I auditioned for two musicals. Both times my auditions were disastrous renditions of what a body can accomplish when trying to produce song while panicking: a mix of croaking, skipped verses, and barely audible murmuring. I got the tiniest parts possible in the musicals. I knew I could sing, I knew I could act, I loved theater, but I was incapable of demonstrating this in that moment to that audition committee.

For years after the results of those auditions were posted on the high school office window, I was haunted by a sense of loss. I felt a similar loss four years later as I completed a piano major in university. I watched peers pass up my piano skills, playing Rachmaninoff concertos and Chopin Polonaises at speeds my fingers could never accomplish.

That rejection opened up space in my life to become someone else — to live in places without pianos and study economics and anthropology. Not every rejection signals a need to choose another path, but some will. As hard as it is to come face to face with limitations, those very limitations free us for new pursuits. God knows precisely the abilities and opportunities you need, and also those you don’t need.

Which prize are you competing for?

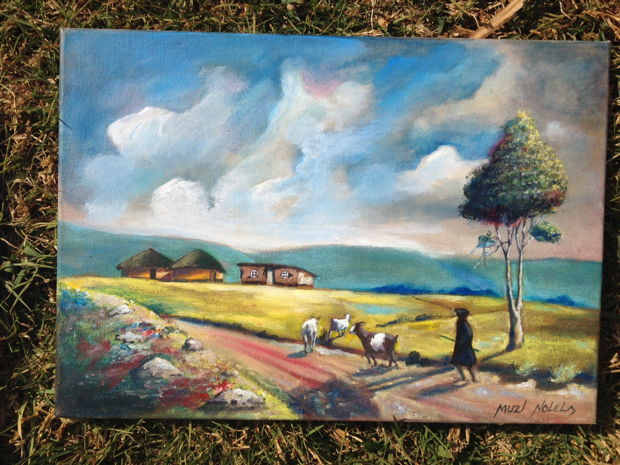

I also can see now that those committees’ opinions of my musical abilities were not the only opinions that mattered. Years later, working alongside coffee harvesters in a Nicaraguan mountain, Nicaraguans begged me to sing the U.S. National Anthem and Christmas carols again and again, propelling us through long work days. More recently in my dissertation fieldwork, my musical background has offered a connection point for long conversations about township life with hip hop artists. Not becoming a professional singer didn’t mean God didn’t have a use for the music I could create.

image courtesy of Radio Free Babylon

Losing a couple of competitions can remind us which competition really matters. As Paul writes, “Run in such a way as to get the prize. Everyone who competes in the games goes into strict training. They do it to get a crown that will not last; but we do it to get a crown that will last forever” (1 Cor. 9:24b-25). A grant award on a CV looks good for a decade or two. The prize that your research and all of your life competes for will last for eternity.