I began my college teaching career at the tender age of 24. Freshly graduated from Baylor University, where I completed both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English, I accepted a tenure-track position at a small Baptist school in an equally small West Texas town.

Being in a room filled with students who were only a few years younger than I was both exhilarating and intimidating, and I spent countless hours researching prior to each class. Night after night, I would stare at the tiny screen of my newly acquired Apple computer (which, by the way, was deeper than it was tall or wide), creating lecture notes from the multiple library books I had checked out on that week’s authors. I aimed for five full pages (single spaced, small font) for each and every class. Although I wasn’t particularly comfortable using the lecture as a teaching method, and I never made it through my entire presentation during the fifty-five minute class, it didn’t matter; I was driven by a near-compulsion to make absolutely certain that I entered each class meeting with significantly more information than I would need.

Though my efforts were motivated by a dedication to teaching my students well, I now realize that the habit of over-preparing was how I remedied my own version of imposter syndrome. Despite my strong academic performance in undergraduate and graduate school, despite the fact that this university had demonstrated confidence in my abilities by offering me a tenure-track position, despite the fact that I’d been one of the first in my cohort to receive such an offer, I sometimes sensed a strangely irrational fear of being exposed as less-than-intelligent or somehow intellectually inferior. Those feelings — understandably intensified by my being a young woman at the beginning of her career — are common in academia, especially amongst women.

After a few semesters, I abandoned the lecture-note quota and became more adept at facilitating discussions — a strategy more closely aligned with my strengths and personality. I remained vigilant about preparing thoroughly for each class session, but as I continued to gain experience, the fears of being “found out” as unqualified to teach in higher education subsided, and I grew more comfortable in my role.

Upon transitioning from a Christian school to my current post as a faculty member at a state community college, I began to sense what I now recognize as a different strain of imposter syndrome. This time my worries were rooted in something much more real: the awareness that my religious convictions, if known, could very well lead to my colleagues’ or students’ labeling me as intellectually inferior. My knowledge of this possibility created more of a subtle anxiety than a pronounced, identifiable fear. But that unease has undoubtedly influenced my interactions on campus, and I’d never quite found words to articulate these feelings—until I encountered Nicholas Kristof’s recent pieces in the New York Times.

A Rhodes Scholar and Harvard graduate, Kristof acknowledges in “A Confession of Liberal Intolerance” that institutions of higher education — the “bedrock of progressive values” with which Kristof aligns himself — have in the past few decades increasingly welcomed all types of diversity except for the religious and ideological kind. Acknowledging the hypocrisy of such a double standard, Kristof calls out progressives for their “liberal arrogance” and invites them to “be true to their own values.” Not surprisingly, Kristof received quite a bit of negative commentary from his readership, and in a follow-up piece, “The Liberal Blind Spot,” he gives an unequivocating response: “Frankly, the torrent of scorn for conservative closed-mindedness confirmed my view that we on the left can be pretty closed-minded ourselves.” He challenges his fellow progressives — especially those in higher education — to “tackle our own liberal blind spot” by more proactively including political conservatives and evangelical Christians as university faculty members.

Kristof’s blunt call for progressives — his comrades — to examine their own shortcomings appeals to me for a few reasons, one of which is the fact that his frustration lies not with those on the opposite end of the ideological spectrum, but with his own “people” — progressives. I too am bothered when I observe conservatives, especially those who claim Christianity, speaking disparagingly about — or to — individuals or groups who don’t share their convictions or political views. Like Kristof, I have found myself longing to challenge my Christian friends to “be true to [our] own values” of loving our neighbor as ourselves — even when that neighbor holds to liberal political views. When Christ-followers participate in any public discourse, it strikes me as crucial that we absolutely avoid unkind, denigrating language of any kind. When the rhetoric used by evangelical Christians ceases to be redemptive and drifts into the kind of hostile condescension for which we have earned so much criticism, I want to distance myself as far from it as I possibly can. Although Kristof isn’t separating himself from progressives — nor should he — I admire his willingness to confront them with such bold accusations.

I also found myself grateful for Kristof’s words: grateful that the call for progressives to practice their tolerance more equitably was coming from within the liberal camp, rather than from without. My sense is that the same words written by a political conservative of any stripe, but especially a conservative Christian, would only reinforce the progressive bias Kristof describes. Indeed, if Kristof is correct in claiming that liberals tend to view evangelical Christians as intellectually inferior, then it’s not likely we will be the ones who convince them to reconsider their double standard; we certainly can’t accuse someone of “liberal arrogance” and expect him or her to listen. But because of the credibility Kristof has already earned with progressives — largely because of his own identification as a liberal — he can do just that. His readers’ strong response is evidence that they heard him loud and clear, that he hit a nerve, that they are weighing his observations.

Kristof’s ideas also resonate for me because he so aptly characterizes something I’ve felt — but not quite been able to name — during my own work in public higher education: the often subtle duplicity of liberal tolerance. Thanks to a college that actively cultivates both diversity and collegiality, I can’t say I have experienced personal discrimination as a result of my Christian faith. Indeed, in my direct interaction with colleagues and students, I have only rarely encountered the kind of vitriol expressed by some of Kristof’s readers.

However, I have observed instances where individuals at my college have articulated their belief that political conservatives and evangelical Christians are intellectually inferior. When that has occurred, I have chosen to ignore such comments, largely because I don’t wish to participate in unnecessary conflict — especially with people whose scholarly work I admire. My choice to avoid controversy in the workplace, however, hasn’t eliminated the sting of encountering such attitudes.

Kristof’s article prompted me to recognize that my side-stepping such conflict is influenced, at least in part, by the fear that speaking up might result in my being thought of poorly, or subjected to unwanted treatment by my colleagues and students. Even as I’ve prepared this article, I’ve been especially mindful — perhaps even a bit anxious — about the potential consequences that could come from drawing attention to my Christianity. In the end, those concerns haven’t stopped me from adding to the conversation with this piece, but I have certainly felt the need to be especially careful in what I say and how I say it.

The reason for my caution is illustrated in the response to Kristof’s articles, including this reader’s observation that “I think we in academia are right to say that the Right, or ‘conservatives,’ have no place in rigorous intellectual departments…." (Robert Brooke, May 31, 2016). As this and other comments so vividly illustrate, the very flaw for which conservatives are often (and justifiably) criticized — an arrogant, condescending, sometimes-hostile attitude towards those who hold diverse views — is also present in those who claim to be progressive. If I confront those attitudes directly, I am opening myself to the possibility of receiving at least disdain if not utter vitriol. Although I realize Christ himself warned his followers that we would encounter such disapproval, I have always feared that my progressive friends’ criticism of my own faith might be justified. What if, in a moment of confrontation, I found myself ill-equipped, either intellectually or emotionally, to respond in a way that would do anything other than increase contempt for me and—more importantly—for Christianity? Because of these concerns, I have been hesitant to speak out about my beliefs when interacting with colleagues.

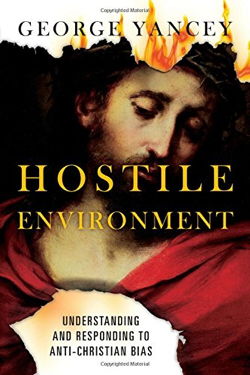

Kristof supports his observations with various studies, including work by sociology professor George Yancey who discusses this topic extensively in his 2015 book, Hostile Environment: Understanding and Responding to Anti-Christian Bias. Yancey explores the reasons behind the phenomenon of “Christianophobia” and also offers guidance for believers who find themselves facing the kind of antagonism Kristof describes — guidance that I found encouraging as well as practically helpful.

Kristof supports his observations with various studies, including work by sociology professor George Yancey who discusses this topic extensively in his 2015 book, Hostile Environment: Understanding and Responding to Anti-Christian Bias. Yancey explores the reasons behind the phenomenon of “Christianophobia” and also offers guidance for believers who find themselves facing the kind of antagonism Kristof describes — guidance that I found encouraging as well as practically helpful.

Pointing out that many individuals with an anti-Christian bias are “less likely to have Christians in their social networks than they are to socialize with people who share their social and political attitudes” (123), Yancey encourages believers to avoid shying away from conversations and friendship with those hostile to Christianity. Instead, he notes that “interpersonal contact can be an important antidote for negative misconceptions and stereotypes” (124). Rather than attempting to persuade people of our faith or making every conversation a debate, our relationships should be characterized by an “attitude of trying to understand” one another (125).

In broader contexts, Yancey insists that believers must “participate in public debate” and do so in “a way that helps us maintain our Christian values...and positively influence” those “who have a prominent place in the public square” (130). He goes on to acknowledge the need for Christians to point out discrimination, even if that means “using strong terms when they are relevant” (125). Yet Yancey urges us be accurate in our description of the unfair treatment and avoid exaggeration (150).

On a personal level, Yancey’s words were both affirming and convicting: affirming because they validated my ability to effectively engage with colleagues who may be hostile to Christianity, and convicting by reminding me that I have shied away from doing just that — largely out of fear that my doing so would have negative consequences. Although I do work at maintaining good relationships with all of my colleagues, I see now that fear has led me to be reticent about cultivating deeper friendships on campus — the kind of friendships safe for substantive conversations, authentic expression, and the mutual exchange of personal convictions, even if those convictions are contradictory. Such relationships require much more time, effort, and energy. They are more complicated and feel far more risky. Yet, as Yancey so convincingly writes, such friendships also offer those hostile to Christianity an example of a Christian — and Christian faith — from a less abstract and more personal vantage point.

My prediction is that I’ll continue to ponder Kristof’s and Yancey’s work the rest of the summer and especially as I return to my college campus soon. I hope to be newly equipped to fulfill my responsibilities as a faculty member in higher education, not as one who anxiously fears being “found out” as an imposter, but as one who is willing to live — and at times talk about — my convictions with steady confidence and humility.