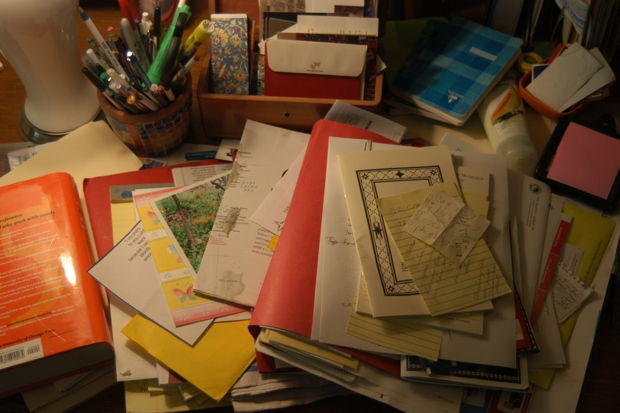

The Tuesday after graduation, dust and detritus littering the top of my desk blotted out a mahogany shine that is neither cheap nor real. I know it’s not genuine because each nick exposes tan pressed wood. Stacked absentmindedly over more months than I care to admit or can even remember, the layers can be itemized as follows: Paraclete Press book catalogs; careful drawings by my children; several handouts, some with diagrammed sentences, one with a paragraph written entirely in words with Old English roots; a Columbia article on Saint Benedict; an e-mail from my husband with Emperor Sigismund’s reported reply to a cardinal who corrected his Latin grammar:

“Ego sum rex Romanus et super grammaticam,” or “I am the king of the Romans, and am superior to rules of grammar,” which — as I tell my students — they are not; two Medieval Academy newsletters; a forty-two page author questionnaire for Shambhala Press; a crumpled Reader’s Digest folded back to the jokes page; letters and cards from friends and students; a slender paperback on humility; a Newsweek article about Facebook; several full manila file folders for future conferences; conference presentations; a book of Martin Luther King, Jr., quotations; refereed articles-in-progress; a colleague’s gift of Bath & Body’s vanilla bean hand lotion in a metallic-green tube; sticky notes with addresses scrawled on them during phone conversations; a stray bright penny; some outdated business cards; a book manuscript four inches thick; printed e-mails highlighted in yellow; neon-pink-and-green rubber bands; an endangered-species 88% extreme dark chocolate bar from a student (and on the wrapper the midnight face and haunting yellow eyes of a leopard); black Expo dry erase markers; a gorgeous blue bowl hand-thrown by a talented colleague and filled with coins for the Coke machine; and a half-used book of stamps.

As with any archeological tell, my cluttered desk revealed my life. First of all, the desk itself is not exactly authentic, the way my job — some call it my “career” — is not synonymous with my self. Don’t get me wrong. I love what I do and hope to dialogue with my students in ways that help them (and me) eternally. I also hope that who I am informs what I do with integrity. But if you could measure my soul against my “college English teacher” role, it would be a little like comparing long-lasting mahogany to O’Sullivan furniture, for no matter how hard I try to be Christ-like, whatever I do is tainted with ego and mistakes. Also, my identity is not synonymous with my résumé, and if I did not teach, I would still be me. As a stay-at-home mom for several years, I experienced this truth, logging countless playground hours sitting in sand with a plastic bucket and hovering near slides.

I love etymologies, and meditating on the word career should reassure me that my teaching-and-writing gig is a “road,” a via through this life (from the Latin carrāria). But my job — I mean, my “career” — has much more in common with the French word, carrière, for “racecourse.” I can’t drink enough strong hazelnut coffee to keep up. Balance is always elusive.

Staring on that gorgeous May morning at the papers and etcetera blocking the wide expanse of my desk, I saw that these bits of clutter represented my life: E-mails from my kind British husband who often thinks of me when he reads something and who even sometimes goes in search of linguistic news that will interest me (surely a miracle after eighteen years of marriage to a hot-headed Cuban-American); a simple sketch in blue pen of a pickup truck, drawn by my first-grade son who is in love with anything that has wheels, and a caricature of me as a funny-looking, bespectacled mouse holding a book, drawn with a number two pencil by my sixth-grade daughter — both offerings of pure love that connect me throughout the day with the two people my heart follows 24/7; lots of stuff to do with teaching; surprising, encouraging gifts from colleagues and students; stuff to do with professional development; and stuff to do with publishing.

Most of all, my piled high and overflowing desk reminded me how much I need prayer. I stared at its tilting mess and thought of the pandemonium that is my daily path. Then I remembered, with some relief, a book manuscript I had just finished on contemplative prayer, by an anonymous monk writing 600 years ago in England. For nearly a year, I translated his Middle English wisdom into Modern English, and during my time spent cloistered with Anonymous, his words settled deep into my type-A marrow:

So, when you feel drawn by grace to contemplative prayer and decide to do it, lift your heart to Him with a humble stirring of love. Focus on the God who made you and ransomed you and led you to this work. Think of nothing else. Even these thoughts are superfluous. . . . You only need a naked intent for God. When you long for Him, that’s enough. (_The Cloud of Unknowing,_ chapter 7)

A hopeless overachiever and self-doubter, I needed to hear that. You’d think I’d be further along the path-of-accepting-God’s-love at forty-seven, but it’s always been hard for me to just “be still and know God” because it’s not a course I can take and earn an A, nor is it a book proposal I can organize. My whole life depends on thinking. I’ve built a career out of trying to think well, working to create prose I hope intelligent, caring people will want to read. But, again, I heard this anonymous, spunky monk advising me:

We can know so many things. Through God’s grace, our minds can explore, understand, and reflect on creation and even on God’s own works, but we can’t think our way to God. That’s why I’m willing to abandon everything I know, to love the one thing I cannot think. God can be loved, but not thought. By love, He can be embraced and held, but not by thinking. . . . Let that joyful stirring of love make you resolute, and in its enthusiasm bravely step over meditation and reach up to penetrate the darkness above you. Then beat on that thick cloud of unknowing with the sharp arrow of longing, and never stop loving, no matter what comes your way. (_The Cloud of Unknowing,_ chapter 6)

All of a sudden, I couldn’t stand the chaos of my desk. I spent four hours cleaning and filing and filling two trash cans full of the unnecessary things. Then I dusted (or swiped at) my desktop with some brown napkins saved from a fast-food restaurant, as I sprayed on AirWash, an air freshener packaged in a bright yellow container that I mistook, with my glasses off, for Endust dusting-and-cleaning spray and kept wondering why it didn’t spread well onto the desktop area nor clean it much, but my desk smells like citrus now. Then with that laminated surface glistening as much as it could with air freshener for polish, I went for a walk.

On my way around the hill that is the Rome Shorter College campus, under a brilliant sun on a gorgeous seventy-something-degree day in Georgia when everything seemed as green as Hildegard’s notion of viriditas, I realized as I walked past towering oaks why my jumbled desk had bothered me so much. It represented my disordered, upside-down priorities. Its confusion was symbolic of my soul’s need for healing. The twentieth-century New York rabbi and author, Milton Steinberg, enjoyed telling the following story about the Hasidic Jew Levi Yitzhak (1740-1810), and his story has helped me understand the lesson of my cluttered desk:

[D]uring the solemn period between New Year and the Day of Atonement, he [Levi Yitzhak] stood at the door of his house, dull, lifeless, altogether out of tune with the season, lethargic under all calls to penitence. And as he stood so, a cobbler came by, looking for work. Spying the rabbi he called: “Have you nothing that needs mending?” “Have I nothing that needs mending?” Levi Yitzhak echoed reflectively. Then his heart contracted within him and he wept. He wept for his sins, for all those things in his soul and life that needed mending, the scuffed places, the split seams, the rundown edges, and the holes. (from Milton Steinberg, Yom Kippur sermon)

Thankfully, God’s mercy is more than equal to my soul-in-need-of-mending. My friend Lil Copan (an editor for Paraclete Press) sent me this reminder recently, a poem by Rabbi Yitzhak on God’s omnipresent and all-accepting love:

Where I wander — You!

Where I ponder — You again, always You!

You! You! You!

When I am gladdened — You!

When I am saddened — You!

Only You. You again, always You!

You! You! You!

You above! You below!

In every trend, at every end.

Only You. You again, always You!

You! You! You! (From David Adam’s The Open Gate: Celtic Prayers for Growing Spiritually)

Or, as the fourteenth-century mystic Julian of Norwich said in her usual reassuring manner to those of us with souls that need repairing:

Would you like to know your Lord’s meaning? Okay, then know it well. The Lord’s meaning is Love. Love is His only meaning. Who shows this to you? Love. What did He show you? Love. And why does He show it to you? For love. Stay in God’s love, then, and you’ll learn more about its unconditional, unending, joyful nature. And you’ll see for yourself, all manner of things will be well. (A Little Daily Wisdom by Carmen Acevedo Butcher, February 14, page 36.)

I was thankful to be reminded that God’s agape love can handle any number of messy desks, confused souls, and fractured communities. And so in gratitude I began to pray, not with grand or planned words, but in the way you talk with your best friend — honest, painful, raw, open, searching, and humble — holding nothing back.