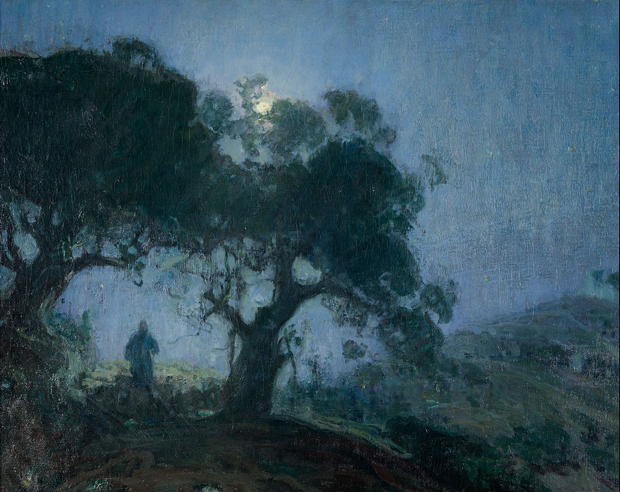

The Good Shepherd by Henry Ossawa Tanner (1902-1903)

I walk a fine line between feeling quite certain of myself and wondering if I’m too much to take in, or if I’m asking too much of the people I’m in deep relationship with. Out of sheer vulnerability here, I wonder if I’m seen as having too many opinions or too much strength of thought. If I’m too loud, too demanding, too silly, too emotional, too… fill in the blank. To balance my strength and my tenderness in leadership and relationship is a real exercise in self-reflection, surrender, and ultimately trust in the one who created all this in one person.

I suspect I’m not alone here.

Many women, in varied circumstances, have had to learn how to both blend in and stand out at the same time. We have come to fear that if we are too much of one thing and not the right blend of another, we will not be heard or utilized to our fullest extent, or we will be dismissed for someone that appears better on the surface. There are so many reasons for this: being in male-dominated professions (particularly academic circles), having to advocate for ourselves, or perhaps being associated with domineering behaviors, like being overbearing or intimidating, when really we’re just exercising leadership. No matter how we learned these patterns, we find ourselves asking questions like, “How do I be myself and still find success in this realm of work?”; “How do I assert my voice without coming off as domineering?”; “What does it look like to be faculty or a leader that invites or commands respect without losing the more tender or softer parts of my personality?”

When we experience this over and over again, we may even start to wonder if it applies to our relationship with God. We might even start asking, “What if I’m too much, even for God?” Sometimes I wonder if my cultural experiences as a female leader have seeped into my relationship with God, allowing them to inform more of my communication with and perceptions of God than He has.

Recently I was introduced to a series of paintings that struck a chord as I reflected about all this. Henry Ossawa Tanner’s first painting on God as our Good Shepherd was done in 1902-1903. It features cool, calm, inviting colors and shadows, leaving one feeling a sense of peace around the gift of God as our Good Shepherd, caring for us in the green, abundant fields. Another similar depiction was completed in 1914, but it is the painting he completed in 1930 that most captures my attention. It features the Good Shepherd precariously guiding his sheep along a high, ridge-line trail next to a great canyon in the mountain of Morocco. It’s arid, featuring browns and dark tones, with light colors used to highlight the gravity of this mountain trek. You see the Good Shepherd and a cluster of sheep barely making it along the side of this mountain, seemingly careful with every step.

When I encountered this painting, I was struck by the reminder that God, our Good Shepherd, goes to the highest cliffs, the lowest valleys, and the scariest of circumstances to find us and care for us. How could I be “too much” of anything for a God like this? The circumstances of Henry Ossawa Tanner’s life may have compelled his heart to shift from the Good Shepherd in the cool, calm grass, to this view of the Good Shepherd hunting us down in the most arid and complicated of places.

Henry Ossawa Tanner is a man, but he may have known a thing or two about being “too much.” He found himself in a position of being too much of one thing, and not any of the thing he needed for success in his early career. He was a man of color in a time rife with racism and persecution in the United States and in the art circles he needed to break into to find success. The son of a father who was an African Methodist Episcopal bishop and a mother who escaped slavery via the underground railroad, Tanner was born in the free state of Pennsylvania. Though raised in a free state, Tanner was not well received by the art community despite studying under some of the best art teachers as the first African American student at the Pennsylvania Academy of the fine arts. This led him to Paris where he became known for his depictions of Biblical stories and finally accepted in The Salon in 1896. I wonder if these paintings invite the idea that if perhaps a man like Tanner, feeling so unwelcome in every other area of life, having experienced the faithfulness of God was now able to see God’s presence and help in every circumstance.

My view of myself grows insecure and uncertain when I forget the magnitude of my belonging to God. What might it be like to take this view of God in the Moroccan mountains with me when I enter difficult meetings, hard conversations with colleagues, or even in challenging moments with my infant son. Could it be that if I found my security first in this gracious and lavish God, that I might never actually be “too much” or “not enough” for those around me? I think so.

How can we shift our mindsets and operate with this kind of groundedness in the Lord? First, we can remember to stop and pray, calling our attention to the help of a God eager to be present with us. This could look as simple as Anne Lamott's framework of prayer, “Help, Thanks, Wow,” with which she entitled a whole book on prayer. Next, we might start to pay attention to when we’re feeling defensive or insecure, noting that it might be an opportunity for us to turn these emotions around and exercise courage, bravery, and assert our voices. This might not be easy but if we can try one action in response to a negative emotion, our heart might follow our feet, so to speak. And finally, it would serve us well to find other women who feel similarly, gather them around, share together regularly, and pray for one another. You might even have to meet over video chat, but the affirmation and validation that comes from a community of like-minded friends and colleagues goes a long way.

God is a big God, our Good Shepherd who created us exactly as we are meant to be. May we all take note of His love and stand secure in every calling and circumstance we find ourselves.