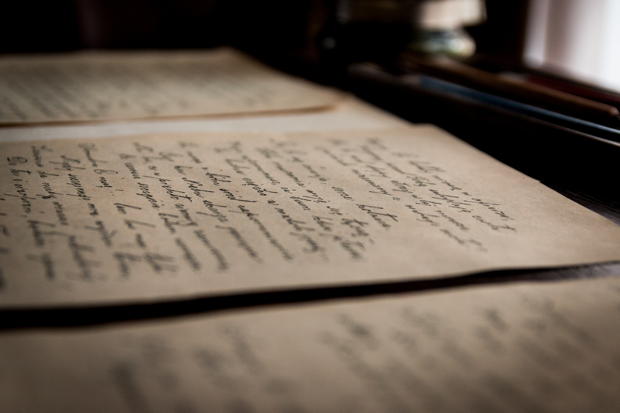

"Luke, I must thank you for your helpful letter. Euphemos and I wonder, however, whether you might be somewhat uncomfortable in your association with Christians. Their reputation throughout the empire is suspect. ... Please excuse our frankness of speech; you are clearly worthy of being treated as a friend, and so we speak boldly on this matter."

- Antipas to Luke, from Letter Collection 4, "They Proclaim a Different Lord"

To supplement the textbook, I assign a piece of historical fiction for the introductory course in New Testament at Wheaton College (IL). Of the several great options available, I have so far used Bruce Longenecker’s The Lost Letters of Pergamum: A Story from the New Testament World. Longenecker’s book takes the form of imagined correspondence between Antipas, a retired Greco-Roman nobleman, and Christians, including Luke the Evangelist. Students almost universally love the book and find that it deepens their understanding of culturally distant aspects of “the New Testament world.” Each semester, I ask students which of the many unfamiliar practices, values, institutions, and so forth stand out to them. And I’ve noticed a telling shift in students’ answers to that question.

Last academic year, my undergrads proved particularly interested in the book’s portrayal of gladiatorial contests and their complex cultural functions in the Greco-Roman world.

Fast forward to this fall, after ... well, everything that happened since last fall — a politically divisive election accompanied by deepening polarization, (white) America’s overdue and faltering reckoning with racial injustice, the persistence of the Covid-19 pandemic and its myriad effects, and more. When I recently asked my students what they were noticing, the gladiators as such only got a few mentions. Instead, numerous students were struck by the curious fact that the letter-writers disagree about various matters (including the merits of gladiatorial contests) and yet address each other politely and continue to engage in respectful dialogue. Without having resolved all of their differences, the letter-writers even develop a sort of friendship.

The shift in what my students reported noticing was probably due in part to my framing of the question this time around: One of the prompts to which they could respond asked specifically about the form of the letters, and I suppose one could see the thoughtful back-and-forth between correspondents as part of the letters’ “form.” But I had assumed students would answer that question (as some did) by making observations about how sender and addressee are named or about other literary aspects of the letters. It had not occurred to me that they might find civil dialogue itself to be a salient feature of the letters’ cultural strangeness.

To be sure, students did not object to the imagined ancient letter-writers’ startling practice of respectful disagreement. Indeed, they found it refreshing. But the fact that students registered such communicative practice as odd, together with the almost wistful way in which they pointed out this unfamiliar way of relating to others, was sobering.

It reminded me that the past several years — marked by increasing polarization, the prevalence of echo chambers, and a growing tendency simply to write off human beings who hold this or that problematic position — form a large portion of these young people’s (semi-)adult understanding of what is “normal.” So much so, apparently, that disagreeing and staying in conversation, or even just disagreeing but still being polite, feels foreign to them.

Lord, have mercy.

I always hope my classes will foster thinking that is at once critical and charitable, marked by both integrity and empathy. But I am realizing that nurturing these skills and dispositions may need to become a more prominent pedagogical goal than it has been in semesters past. I am realizing, too, that I need to make a more concerted effort in my own life to practice dialoguing across differences. The past several years may have had a disproportionately distortive effect on young people’s perceptions of normal communication, but we have all been swimming in these choppy cultural waters.

What about you? In the various roles and relationships in which we find ourselves — as professors or other professionals, as parents or adult friends of families, as members of churches and other communities, as participants in social media conversations — how might each of us help ourselves and others to (re)learn the art of reasoned disagreement that does not end a conversation, or even prevent a friendship?