“Farr off the empyreal Heaven…

With opal towers and battlements adorned

Of living sapphire.”

John Milton, Paradise Lost

One of my more memorable substitute teachers in elementary school wore a giant opal ring on her forefinger. She was a tall matronly woman with white pixie-cut hair, and she wore a pungent rose-scented perfume that hung thick in the air as she paced the aisles between our desks. I am sure she was a lovely person, undeserving of my spite, but I have never forgotten the peculiar smell of her perfume or the sinking disappointment I would feel when I saw her, knowing my beloved fifth-grade teacher, Miss Hastings, was gone that day.

I’ve been strangely skeptical of opals ever since. And apparently, I haven’t been alone. The early Greeks believed opals held magical and prophetic powers. In medieval folklore, they signaled evil and bad luck. Some even thought they were harbingers of the Black Plague. A popular legend held that carrying an opal would confer occult powers like invisibility. In 1631, Ben Jonson wrote of, “no med’cine, Sir, to goe invisible…Nor an Opal Wrapt in a Bay-leafe, i’ my left fist, To charme their eyes with.”

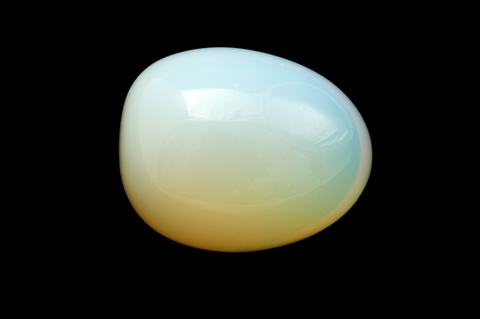

Why did this precious gemstone inspire such darkness? It may have something to do with the opal’s unique composition. While other precious gems are admired for their brilliance and clarity, most opals are dense and opaque, almost milky white. And unlike diamonds — renowned for their unparalleled strength — opals lack form, having no patterned arrangement of atoms. They contain, as one source describes, a “disordered structure.” The opal’s famous “play of light” depends on this flaw, producing color through refracted light that bounces randomly off these irregular spheres inside the stone. As a result, they are surprisingly fragile and imperfect, possessing few of the qualities conventionally associated with beauty, like strength or symmetry.

During that same fifth-grade year of elementary school, I discovered opals, with their flaws and imperfections, were my birthstone. My best friend Susan was born in May, and the emerald is her trademark. In ancient Rome, the green of the emerald was the color of Venus, the goddess of beauty and love. Fitting, since Susan was the most beautiful girl I knew. She looked like a china doll with porcelain skin, jet black hair, and blue eyes as round as saucers. When Barbizon modeling came to our elementary school, they scouted Susan. They wanted an emerald, not an opal. Years later, when all my closest high school friends were nominated to homecoming court without me, I blamed the opal once again. Since then, it has been present for every rebuff, every bewildering breakup, and every insult. The opal looms even now during stolen hours spent studying my reflection, imagining a profile without an all too distinctive Roman nose (a family heirloom). Like those medievalists, I blame the opal’s curse, still.

In the mythology of my youth, the opal was evidence of my mediocrity, feeding my inner critic with the notion that I, too, was inherently flawed and would never quite measure up. I always assumed middle-age would bring an end to such nonsense, but that ten-year old voice still denies me the joy of self-acceptance, telling me that I’ll never arrive. It reminds me that I’m certainly not a writer, or a runner, a good mother, or even a real scholar. The voice convinces me that I’m an interloper in a world of ideals, and I find myself, on the eve of my fortieth birthday, asking the same question I posed in fifth-grade. Will I ever feel good enough?

God answers me with the image of the opal, mysterious and inscrutable.

In her spiritual autobiography, When the Heart Waits, Sue Monk Kidd describes the “opaqueness of midlife” as a time filled with many more questions than answers. In my season of midlife, I feel as if I’m peeking through a cracked door into a dimly lit corridor or peering into the density of an opal. I have unanswered prayers, and I live without things I once thought impossible to lose. God holds my feet to the fire, and I wonder if my childhood fears might just be real: that I have lost so much — things far worse than homecoming votes — because I am not good enough to have them.

Unable to see any answers, I listen.

Scripture tells us that, “He is our God; and we are the people of his pasture, and the sheep of his hand. Today, if we will hear his voice.” Hearing is the sensation most vital to a relationship with God, but this kind of hearing is not bound by material reality. As Sarah Young describes in her book Jesus Calling, this hearing involves, “tuning in to an ultimate reality. [God] is far more Real than the world you can see, hear, and touch.” There, beyond the limits of sensory perception, God’s voice is loudest.

In my doubt, God speaks silently and says that the solution lies not in any visible proof of perfection but in the very lack and need that prompt my anxiety: in the tension-filled gap between question and answer, knowing and doubting, that often characterizes both adolescence and midlife. From there, He says, the answers will come. And so, with youthful pretense and illusion long since stripped away, I dwell in the stark yet fertile space between want and gain, forced to wait and confront my deepest doubts. In them, God has much to teach me about living with what Oswald Chambers called “gracious uncertainty.”

I am a weak and deeply flawed vessel, and I desire beauty instinctively because it holds the promise of restoration, healing, and wholeness: a momentary reprieve from a broken world. What is beauty if not a glimpse of something good, otherworldly, and eternal? But, this earthly promise of beauty proves most unreliable, nothing more than a chimera or a temporary fix, and pursuing it has left me chasing my own tail. The only way out is to look elsewhere — beyond self and world — towards lasting truth and healing.

The Romantic poet John Keats believed the way to such truth was through poetry and the careful cultivation of what he called “negative capability,” or one’s ability to “stand in uncertainties, mysteries, and doubts without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” He believed in the value of “half knowledge” as a way of approaching beauty and, ultimately, eternal truth, for according to the poet, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.”

Given the fact that his short life was marked by overwhelming grief, I can only think that the “beauty” Keats describes is not the conventional kind but rather that same brand of negative beauty I see in the opal. I suspect that is why Keats chose the nightingale as a symbol of the poet — an outcast who sings despite a reality of darkness, for the poet receives prophetic and poetic insight through, and not despite, his pain. “But here there is no light,” Keats writes in Ode to a Nightingale, “save what from heaven is with the breezes blown/Through verdurous glooms and winding mossy ways.”

Ironically, such darkness can draw us closer to the light of a God not bound by contraries. In Psalm 139, David cries out to God: “Even the darkness will not be dark to you; the night will shine like the day, for darkness is as light to you.” His light shines brighter in darkness; in folds of doubt, his presence is more palpable and real. When we submit to the shadows in life, we experience a quickening of his spirit, for we can see most clearly at times when, like Keats’ poet, we are shrouded in night. What else but this divine notion of darkness as light could explain the curious case of the opal?

I am learning to value my birthstone’s unusual beauty as a reminder of the power that resides in the surrender and of the truths that lie beyond reason. I remember that opals are far more rare than diamonds and unlike any other opaque gem contain spots of shimmery color: pied speckles of pinks, greens, oranges, yellows, and purples. And I recall riding a pontoon boat on Lake Huron one twilight evening two summers ago when the sky exploded in opal, the color of vespers, capturing that moment between day and night when time sits still in iridescence.

Under the opal sky that night, I thought about the seventeenth-century poet John Milton and how he wrote his epic, Paradise Lost, after losing his sight at age 44. The story goes that he would wake each morning with those lines of blank verse fully formed in his head, composed in his dreams and suspended there in that sacred space beyond the senses until he could recite them to his daughters. His masterpiece was completed nearly ten years before it was published in 1667, the year after the Great Plague and the Great Fire of London, standing as a stone monument of hope in the midst of unthinkable horror and loss.

But I also remembered that this astonishing achievement came only after a period of agonizing stasis. Like the long-suffering Keats, Milton found solace in something akin to negative capability, writing in the sonnet “On His Blindness”:

“God doth not need

Either man’s work or his own gifts: who best

Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best. His state

Is kingly; thousands at his bidding speed

And post o’er land and ocean without rest:

They also serve who only stand and wait.”

Faith. That is where I rest now — where we all must — standing still in the dark knowing of uncertainty, waiting on God and learning to love the unlovely in life, and in myself. And in the opal.