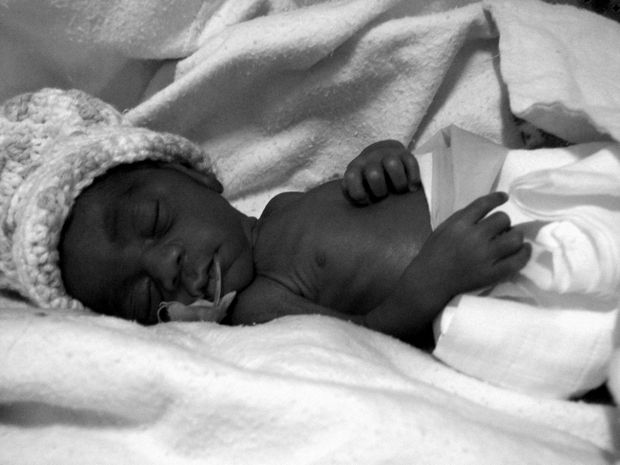

One-month-old Blessing cried inconsolably in the hospital chaplain’s arms. Beset by intense hunger, she was unaware of the true magnitude of her loss: her mother had died earlier that morning of meningitis.

My walk to my morning rounds at the Mbingo Baptist Hospital in Cameroon had been interrupted by Hosea, one of the midwives. “Dr. Jao, do you have more of the breastmilk you’ve been pumping in the guesthouse? We need to give it to Blessing quickly.” When I returned from the guesthouse with the milk, I saw Blessing’s grandmother crying and her grandfather grieving with his head bowed down. And then I saw Blessing. The chaplain held and rocked her as she continued to cry. Through a translator, the grandmother told me that Blessing had last eaten at 8 p.m. the previous night – twelve hours ago.

I looked at my frozen breastmilk and realized it would take another hour to thaw the milk, find a sterile bottle (hard to come by in Africa), and warm it. Blessing’s cries became steadily weaker as she seemed to be losing hope of ever finding milk. My heart broke, and I did what only a lactating mother could do: I took the baby into my arms, opened my shirt, and let her nurse on me.

An Inopportune Time for Research?

Last January, I felt frantic and conflicted when we discovered I was pregnant. I was planning to be in Africa to set up a research project in early September 2008 – my due date. “How could I be both a mother and a researcher?” I wondered. Providentially, God arranged everything. I received two major grants last summer. The grants allowed me to change (and shorten) travel dates, hire a Cameroonian study coordinator to collect the data, and extend the research window to accommodate my pregnancy.

With the support of the chair of our Infectious Disease department, I flew to Cameroon this January to set up a study of kidney disease in pregnant women with HIV in partnership with the Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Board at the Mbingo Baptist Hospital and at the Nkwen Family Care and Treatment sites.

Nevertheless, the day I left my four-month-old daughter, Madeleine, in New York, I cried as I pumped and dumped my breastmilk to the sound of other crying children on the plane to Africa. I knew Greg and my parents would care for her, but I felt as though I was a horrible mother who had abandoned her daughter.

As I nursed Blessing, I caught a glimpse of God’s redemption of this trip. She continued to nurse, and her crying ceased. We locked eyes, and I felt a wellspring of compassion inside me. “Perhaps this is a small taste of what Jesus feels for us,” I thought. When I finally looked up, I saw a large circle of Cameroonians staring at me. Later, Eileen, my study coordinator explained, “We, as Africans, never imagined a white woman, who is in our minds superior to us, could ever serve a black baby in such a way.”

A Reminder Life Brings Life

I later learned that a mother of a 28-week old preemie heard the story of Blessing. She had questioned whether she should let the doctors feed her baby the “white woman’s milk” through a feeding tube. (Her baby’s suck was too weak and her milk had not yet come in.) She decided to go ahead. He started gaining weight by the time I left Africa. In the midst of death and destruction, God showed me life and love. What a privilege it has been to be a part of his work in the lives of these babies. And, at least in Cameroon, I am known as the “white woman doctor who give her bobby to black baby.”

A Reminder Death and Suffering Continue

The mother told me in pidgin English that Mackelly, her 18 month old son, stopped walking a few days ago. We noticed a fever, limp legs, and a crying boy on our quick exam. Antibiotics were started, but the lumbar puncture would reveal no source obvious infection.

The next day Mackelly’s mother reported that the child was unable to use his hands to eat, and that morning on rounds, I noticed him breathing in distress, heaving and fighting to get air into his lungs. His paralysis was ascending quickly, and I suspected Guillain-Barre’, for which we had no cure. I explained to the mother that the child would likely not make it as we had no means of providing mechanical ventilation in Africa. She looked at me in both fear and disbelief and told me she was going to run and fetch the boy’s father. I nodded and told her to hurry. Then I turned back to the boy. My maternal instincts surged, and I wanted to pick him up and cuddle him. But I knew he would be frightened by the “white woman” trying to comfort him. So I turned to his aunt and asked her to pick him up and hold him. “He’s scared,” I explained. “Hold him, so at least he’ll know that he is loved and is not alone.”

Thirty minutes later the aunt began to wail, and I knew he had died. He died struggling to breathe as his lung muscles became paralyzed, without either of his parents at his side.

A Reminder to Keep Hoping

Flies swarmed around the bed of a little three-year-old boy. Dr. Aschi busily swatted them off the blankets as he presented the case to me. I listened intently, torn between the desire to be a sharp diagnostician with a medical cure and to be a loving mother ready to hold and rock this boy to sleep.

Mannas’s tiny body was so overheated that his sweat had soaked through the thin dirt-covered sheets. He had AIDS and had been recently started on ARV’s (antiretrovirals). He had been doing well until last week when he had begun having high fevers, swelling around his neck glands, and swelling around his belly. His liver enzymes were extraordinarily high, and his hepatitis C test had been positive. He had probably received one too many blood transfusions as an infant. I ordered several other lab tests and started him on antibiotics.

Two days later, tests confirmed what we had suspected: Mannas had disseminated TB. We started a 4-drug TB regimen, readjusted his ARV therapy and waited. Every day I walked by his bed only to see the fevers continue in his listless body. Nearly one week later I finally saw him sitting up, eating a banana, and ready to shake my hand on morning rounds. His mother smiled and told me he was finally returning back to normal. One small victory here in Cameroon as God continues to remind me that He is greater than the suffering I see, greater than the disease that ravages the lives of innocent people, indeed, greater than death itself.