It’s the second-to-last week of the semester, which for many professors is the most intense stretch in the academic term. Though I’ve been at this job for quite some time, the sheer exhaustion I feel during these weeks often takes me by surprise. All it takes, though, is one stroll down the hallway of my department and a few conversations with colleagues to recognize I’m not alone. Most everyone around me feels buried under a mound of work, and the word “exhausted” is one I find myself using and hearing more often.

Almost exactly one year ago, while trudging through the very same sense of exhaustion, I found strange encouragement when I happened upon two articles acknowledging the existence of this experience for faculty. One piece appearing in Inside Higher Ed includes boundary-setting advice from a former faculty member who admits to having struggled between feeling “like I wanted to be the professor” and caring “so deeply about my students that I wanted all of them to feel seen, heard, and supported in their growth.” In a related Chronicle of Higher Education piece, an anonymous faculty member details how students’ and colleagues’ appreciation of her willingness to listen often results in expenditures of her time and energy that go unnoticed by her institution. Her observation, that it is usually “a small group of academics — primarily women — [who] end up taking on this kind of care-work at colleges and universities,” not only because they are often inclined to do so, but also because this is a common expectation of women working in higher ed, still rings true for me.

The author is quick, though, to emphasize the very problem I felt as my tired eyes read her words: “Listening, empathizing, problem solving, and resource finding take an enormous amount of time and energy.” And, as I seem to re-learn every year, the intense exhaustion many faculty feel is more than physical — it’s emotional, mental, and even spiritual. It’s compassion fatigue.

I would imagine most educators — especially those who have taught for a while — would admit to understanding the concept of compassion fatigue. Some might confess to experiencing it from time to time — perhaps even to a significant or detrimental degree.

It can be risky, though, to acknowledge having really struggled with this experience; truly competent professionals shouldn’t and wouldn’t have to cope with this sort of emotional and intellectual limitation, right?

A teacher’s inability to fend off compassion fatigue could be symptomatic of a deeper, more problematic emotional and intellectual frailty. For a Christian faculty member, it may be symptomatic of some sort of spiritual deficiency.

But maybe it’s not.

Perhaps compassion fatigue for teachers can be attributed, at least in part, to simple numbers.

Consider the story of one professor who serves on the English faculty at an open admission community college with a student enrollment of over 10,000. In some semesters, her classes consist of well over 100 students for whom she wants to be an effective teacher, not only covering the required subject matter, but also doing so in a kind, caring, and compassionate way. Not only does she want to learn all her students’ names, but she also wants to know their stories and understand what types of classroom experiences they do and don’t enjoy. She wants to answer their questions, help them with their papers, meet with them to discuss study strategies that will work best for them. Many times, those meetings involve discussions that move beyond academics and into helping them navigate a range of barriers that often create a very real threat to their academic goals.

This professor wants to accomplish all of this in addition to preparing for and teaching her classes with excellence, serving on committees, attending departmental meetings, participating in campus events, and serving as an academic advisor during registration.

And then there is the paper grading. If 100 students each write 6 essays, she will have 600 essays to grade in a given term. If it takes approximately 30 minutes per essay (which, in some cases, is a conservative estimate), she will need to devote 300 hours to grading over the course of a 15-week semester. That means 20 hours of grading per week, in addition to her other duties.

But that’s not all. We can’t ignore the time, energy, and attention this professor must give to students facing problems outside of class that interfere with their ability to complete their coursework. During a recent semester in a single class, she encountered issues ranging from cars that stopped working, fuel tanks or cupboards that were empty, computers that crashed, parents who were hospitalized, increased work hours, or mental health issues that were flaring because of the pressures inherent to college work.

My work assignments this semester involve less teaching, but I know many of my colleagues are carrying a load similar to what I've just described. For me, the reduction in teaching hours involves an increase in responsibilities that bring me in contact with an even greater number of students who face serious difficulties. Regardless of our work tasks, I see so many who continue striving to genuinely care about each student. But as the semester moves into its final days, I am more than a little overwhelmed, and I sense I that am not alone in this feeling. As our students' end-of-the-semester needs and concerns intensify, it becomes increasingly difficult to continue responding in the kind, thorough manner we want to offer each student and colleague we encounter.

I can't speak for others, but during this stretch of the academic term, I find myself wondering whether my weariness is the unnecessary result of poor planning, a lack of resilience, or inconsistently maintained classroom expectations.

Maybe, though, my brush with compassion fatigue is the unavoidable product of an educational system that needs to be re-examined. Of course, that conversation would require more energy than I have to offer.

Meanwhile, we are still here. I am still here — feeling the guilt, frustration, and second-guessing that accompany compassion fatigue — not only wondering what I can do, but also grappling with serious misgivings about whether I have the capacity to do anything at all.

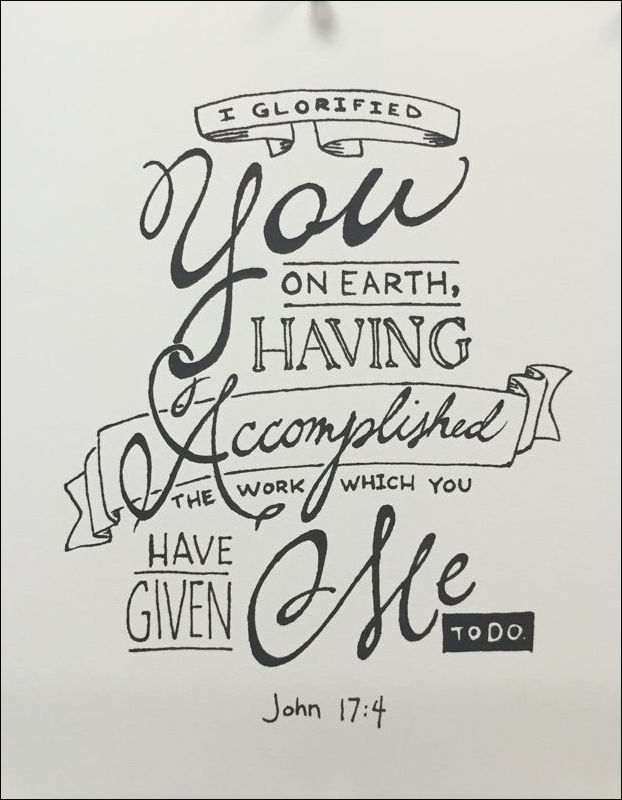

On the wall above my grading desk hangs an artistic rendering of a passage from John’s gospel. Christ, praying in the presence of his disciples just before he is arrested, makes a statement that shows his single-minded focus:

“I glorified you on earth, having accomplished the work which you have given me to do.” — John 17:4

At the time I received this print, I didn’t realize how powerfully Christ’s words would re-align my perspective during days when I fear the possibility of smothering beneath the workload remaining until the end of the term. But today I do.

Today, Christ’s prayer reminds me how easy it is to succumb to compassion fatigue when I forget that I need only do the work given to me for that day:

- Meet the students who ask for help during office hours.

- Teach those who come to class.

- Talk with the colleagues who attend the day’s meetings.

Christ’s focus on the work the Father gave him reminds me that I can do the same, and that I can release both my fatigue and the outcomes of my labor to his faithful provision.