Listen in on our podcast as Stephanie Gehring performs a reading of her piece "Wheat."

Wheat dies so many times. The kernel goes down under the earth and its hull rots and wrinkles and disintegrates. The little spike of life unfolds, unsheathes and goes up slowly. It turns green in the light.

Can it be the stems of wheat do not feel what the wind does, moving through them?

Garter snakes die at harvest, rabbits, field mice. The combine does not know what it cuts.

The stalks make straw, shining but sharp. They’ll stab you in the hand if you aren’t careful. The grains are beaten out from their symmetrical arrangements, taken away in trucks. Poured into grain elevators, where they can suffocate a man in minutes. The kernels lie in heavy, gleaming piles. If you run your fingers through them they are cool and if you put them in your mouth they’re small and hard to chew. At first they taste dusty and then sweet.

• • •

When I went to visit my dying grandmother, I took loaves of bread my mother said Grandma likes. She usually makes fun of gifts, but she smiled shyly when I told her I brought her favorite bread, one loaf to freeze and one to start now. You remembered.

Grandma’s stomach is bleeding and her colon hasn’t worked for years, empties into a pouch attached to her stomach which terrifies her by leaking. It leaked when I was there. I picked new clothes for her, and when I helped her out of the old ones, and slid the new ones over one limb at a time — lift your foot now, there we go — she shocked me by saying, Your hands feel like they’ve done this before.

Ninety years of bitterness vanished from her voice, just like that, her face open as the face of a girl who does not know what disappointment is.

My uncle is taking care of her when the nurse isn’t here. He is fifty and dying of loneliness and cigarette smoke. On the kitchen windowsill there are a dozen little jade plants and spiky dark green succulents, small, as though they’ve only just been separated. One is in an orange-enameled camping cup with a handle. I wonder how long he will remember to water them. Weeks later I realize he is the one who potted them; he is the one who kept the grass shining and green; he is the one who trained hops on a three-story trellis between the machine shed and the old cow barn.

• • •

Mary — there were so many of you: Magdalene, mother of Christ, sister of Martha. That night in the upper room, none of you ate with Jesus and the twelve. Did you bake bread for their Passover? A woman somewhere crushed the kernels between millstones, ground them to powder. Added no leaven, which meant less waiting. Kneaded, with water but no oil, shaped loaves and slid them onto stones over fire till they hardened, browned, grew brittle to break and eat.

You were not there in the room when Jesus took off his outer garment and tied a towel around his waist like a common servant. Six days before, it was one of you women who anointed Jesus’ own feet with perfumed oil, using her hair as a towel. Judas said what a waste it was, expensive perfume on feet. But Jesus said she’d be remembered for her love.

Footwashings are awkward in church, anachronistic, strangely intimate. But footwashings outside church are much harder. As footwashers in church we can at least be proud of our humility. It is at home, at work, with no one watching, that servanthood is what it was in that room: a chosen, unforced submission, a reversal caused by love. And the submissions that count most are the daily ones, the ordinary ones without fanfare.

• • •

This thing we do in remembrance. Blood, wine, bread. I remember so weakly.

My goal is God himself not joy nor peace, the song says, and my heart sinks, knowing it’s not true. Too many days I’m not even aiming as high as peace. The song repeats, as though the writer needed to practice believing it too. Nor even blessing but himself my God.

All the stories: about walking into darkness. About staying awake in the night. About killing last hopes and losing the very ground under our feet, feeling sure nothing could break our fall without killing us.

And maybe you do kill us, God, when we give in to your only son’s death. We with our helpless hands knotting, forgetting how to dress our bodies. We with our eyes losing focus, and our tongues slowing down till they still. These are inevitable, they have nothing to do with submission. You’re asking more than this. In these mortal bodies you ask us to come to death on purpose, though death is so wrong, though it takes what is not rightfully its own.

At any cost, dear Lord, by any path.

And love can trust her Lord to lead her there.

You ask us to step into the darkness, which is coming for us even if we stand still; you ask us to fall like kernels of wheat with wills, to choose the earth.

To go under with your son and watch the grave-rock, like a millstone, seal us in the ground.

To hold still though there is no light anywhere, and it is so hard, in the heavy dark, to believe in dawn or in shoots turning green.

This meditation was originally read during the Maundy Thursday worship service at New Life Presbyterian Church, Ithaca, New York.

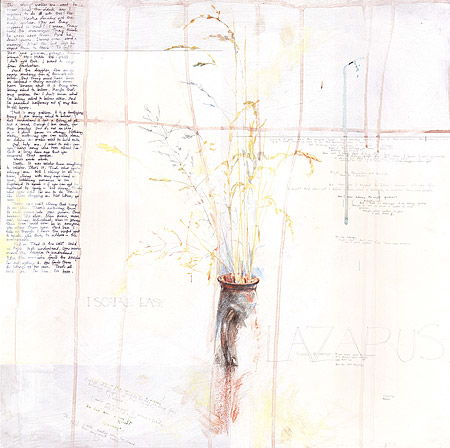

Art by Stephanie Gehring. Go to www.stephaniegehring.com to see more of Stephanie’s artwork and words.