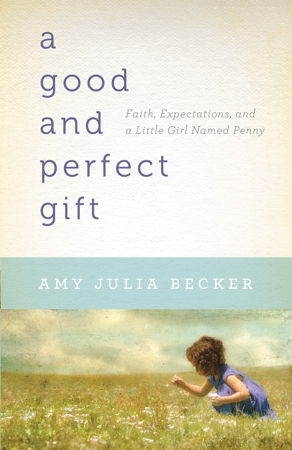

Amy Julia Becker was an MDiv student at Princeton Seminary when she gave birth to her first child, Penny, who was diagnosed with Down syndrome. Penny’s birth led Amy Julia to a new understanding of the concept of perfection and to write the book, A Good and Perfect Gift: Faith, Expectations and a Little Girl Named Penny. We heard Amy Julia speak at the 2012 Festival of Faith and Writing at Calvin College and asked if she would address our audience of women who, much like her, prize intelligence and pursue academics, and discuss how her ideas of perfection have changed since Penny’s birth.

A report of a study at Duke University found the women students seeking to be, in one student’s words, “effortlessly perfect.” You began life yourself as someone who wanted to do things right, to be perfect. When some senior high school girls came to visit you and Penny, they kept saying, “You have the perfect life.” What were they seeing and what did they seem to be longing for in their own lives?

Our culture upholds an idea of perfection that I have bought into in various ways for my entire life. I thought perfection had to do with getting everything right all the time, not needing to ask for help from other people, and conforming to a set of cultural ideals.

By cultural standards, I didn’t have a perfect baby. Because Penny had Down syndrome, I was startled by the girls who said I had a “perfect” life. I then started thinking about Jesus’ words in Matthew’s Gospel, “Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly father is perfect,” and I wondered what he meant. I looked it up, and the root of the word translated “perfect” is telos, which can also be translated as “whole” or “complete.”

God doesn’t want for us the perfection that our culture imagines, perfection as flawlessness and radical independence from one another. But God does want wholeness for us. Penny has helped me to see that ironically wholeness comes from admitting our need for one another and giving and receiving love to and from one another.

I think those girls glimpsed wholeness in our lives, even though to me it felt quite fragmented at the time. The possibility of wholeness was present in that we had this fledgling family with great love undergirding us all.

In A Good and Perfect Gift you write, “It was as if having kids had become an equation: youth plus devotion to God plus education equaled a healthy and normal baby. As if taking a birthing class and reading baby books and abstaining from alcohol and praying all guaranteed certain things about our family.” I think there is an implicit understanding many of us as Christians have that we will be rewarded for doing things right. How has this changed for you?

I think whenever we start to understand our relationship with God (or other people) in terms of working hard for a reward or working hard to earn our pay, we change the terms of the relationship. God wants a relationship with us that is based upon grace, based upon giving and receiving.

We, like Adam and Eve, want to change that relationship to one of bargaining, as if our behavior can control God. On a human level, it is really tempting to see one another as consumer products instead of God’s image-bearers. Even as a mother, I had seen my baby as a product of sorts, and when she was deemed “defective,” it was almost as if I wanted to return her or at least demand an explanation from the store manager.

In time, of course, I realized that Penny was a gift. Not a product. But a gift. I hope that having her in my life has taught me first and foremost to see other people as gifts instead of products, but also that God is not under my control, not predictable, and that God doesn’t need to answer to me even when I don’t understand something.

Your husband Peter’s prayer: “I have prayed for so many years that my heart would become more open” seemed to be answered with Penny’s birth. How do you think hearts can open or close with something like Penny’s birth?

I eventually realized that having Down syndrome made Penny more vulnerable — physically, medically, socially — than a typically-developing child. As her parents, we would either choose to be fully associated with her and take on her vulnerability as our own or we would to some degree reject her as a way to protect ourselves from that vulnerability.

I think every child pushes parents to either open or close their hearts. Children with disabilities might just push a little harder.

How have you seen your own attitudes change as a result of parenting a child with Down syndrome?

The biggest change for me has been believing that every human being I encounter — from the lawyer I meet at a cocktail party to the woman replacing the ketchup in the cafeteria — has been created with a purpose in the image of God. From there, every human being has something to offer to me, a gift to offer me, if only I have the opportunity and willingness to receive it.

I also believe that I have gifts to offer to others and that we all need one another, no matter what we look like or what our SAT scores add up to. This attitude has produced greater joy in giving of myself and greater humility in recognizing my own need for others.

After Penny’s birth you describe a time where you had difficulty praying. You thought of yourself as being “stuck” until a friend described it as a period of fallow ground. How do you see the difference?

We — and I very much include myself in this — are just so impatient! So much of Scripture has to do with waiting. I think of the Israelites in Egypt or in the desert with Moses or waiting thousands of years for the Messiah. And then Jesus waited for his own time to come, waited for forty days in the wilderness, and even waited for God as he hung on the cross. And of course there is our own constant waiting for Jesus’ return.

Rest is also a theme throughout Scripture, and, like waiting, a theme our culture would rather ignore. But God both commands us to rest and gives us the possibility of rest. I think waiting and resting are interrelated, and when we understand a “stuck” place with God as a season of waiting and resting, perhaps it will help us to believe that something might just grow in the soil of our hearts again.

How do you see us — especially in academic settings — overvaluing the life of the mind? How can we value it but not make it a god?

God gives us the life of the mind, and he calls some people in particular to cultivate the life of the mind for the blessing of many. But whenever that calling inhibits love, inhibits hospitality, inhibits the fruit of the Spirit, we’re in trouble.

I wrote in my journal when Penny was young: “Can she live a full life without reading Dostoyevsky or solving a quadratic equation? I’m pretty sure she can. Can I live a full life without learning how to love those who are different from me? I’m pretty sure I can’t.” When the life of the mind doesn’t include love it becomes an impoverished life.