Ruth, you finished your PhD in genetics, but made the decision to work outside of the lab?

I finished my PhD, started a post doc, and I thought, "It's so all-consuming. I want to do other things outside of the lab." So I left. I wasn't that patient with experiments. I like to learn things, but not focus on one thing all the time. I had always been interested in science communication, in museums or science festivals and things. But I then saw a job advertised with Christians in Science [similar to the American Scientific Affiliation (ASA) in the US]. They'd never had staff before.

This was their first paid position, half-time Development Officer, to try to get new members in, especially younger members. And I loved it. It matched exactly the kinds of things I enjoy doing. Then a couple of members of Christians in Science set up the Faraday Institute, an academic research institute in one of the colleges of Cambridge University, for interdisciplinary research and communication about science and faith, to help people have an informed discussion about science and religion.

Many of the staff are Christians, but you don't have to be a Christian to work there. I'm called a Senior Research Associate, so I have academic input — I have my own project and research topic, but my main focus is to reach the general public, especially the church.

And your book,

God in the Lab?

Yes, I did that as part of my work. The book is targeted toward Christians in general. And then hopefully they will share with their friends who they might talk to about science and faith. So, trying to put something in peoples' hands that's not the usual debates, but something else, to help them see the beauty of science and how science can enhance their faith.

I know you have a passion for women who are in academia, and particularly in science.

Yes! At the Faraday Institute we make an effort to draw in female contributors and speakers. I think at the more senior level, that was the generation where there were fewer women in science. So the ones that are coming up, the women who are contributing in terms of science and religion, are running around doing a lot. For both men and women, there's a stage mid-career when you're trying to establish yourself academically and independently, and get funding and run a lab, or manage a lot of people. It's very hard to find time to contribute to something about science and faith. [Laughing] So we tend to lose people a lot there.

I keep in touch with a couple of friends, women in science, who were about a year ahead of me. And they’ve both gone on to set up labs. One of them has a family and one of them doesn't. And I've seen the challenges. I mean, it's very challenging setting up a lab anyway, but being a [woman] and then also having a family. There are challenges and people don't always know how to support you. I think one of them has a lot of women in her institute who have families and they have really supported her, which is brilliant. But a science career is not necessarily set up for women, especially with a family.

I see the Evangelical church is learning how to encourage women to pursue their calling in different ways. And it's difficult, because there are different trends in culture, different trends in the church, not all of which are Biblical. I’ve come to the conclusion that people just have to figure out what their calling is for them and for their family. Some people want to stay at home. Some people want to work. Some people want to do both, which is difficult, but people need to find what is right for them and the people around them.

I want young women to feel that there isn't just one track. You know, they shouldn't feel guilty if they don't want to work. And they shouldn't feel guilty if they do. And they shouldn't feel like one way is more spiritual than another.

Did you have support from your church when you were in grad school?

Yes. I was in a regular mid-week Bible study group. It was full of all sorts of people, and some of them were academics. There was a professor, and there were a couple of girls who were doing PhDs. And you know, I got to the point when I was writing up my PhD and I was trying to go along every week to Bible study. I was an empty head on a seat and I just had to say, "Guys, I'll see you in three months." And they said, "Fine! Go and write your PhD. Come back when you're finished. We'll pray for you!" They were so great.

Yes! You presented today about beauty in the sciences, and it sounds like you were trying to decrease the fear that people might have of science. Can you speak to that?

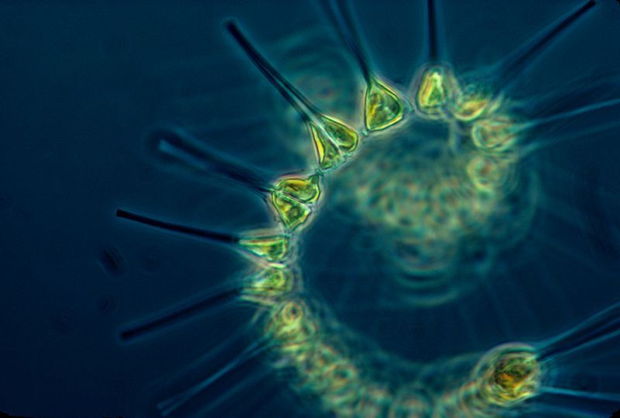

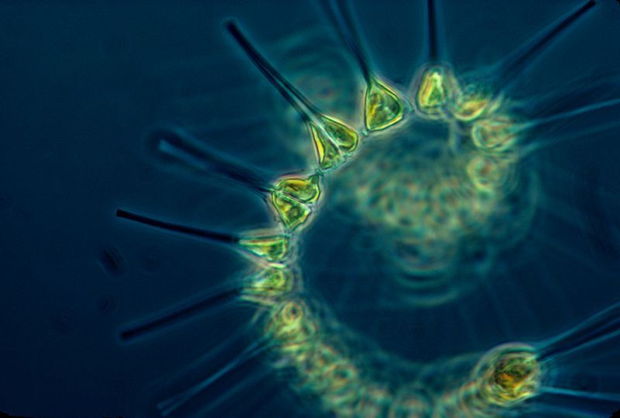

Yes. I just want to help people realize that this is the world God made, scientists study it, and there's nothing to hurt us there. If God made it, it's a good thing to find out more about it. The more we find out, the nearer we get to the truth, hopefully. And what we find is that there are things that are beautiful. We lose ourselves in wonder. There are things that give us a feeling of awe. And those are the rewards for the scientist for all the hard work, when you drop your experiment on the floor and you lose six months of data. Whatever it is, not every day is filled with wonder. [Laughing]

But understanding that for the scientist, it's a discipline of daily looking and examining and asking. There are very tiny steps you make every day. A lot of science is just making up the solutions you need for an experiment, and experiments can have so many steps, they can take several days. And then you start again, and you have to teach the students, or you have to order things, or hire someone. There's just so much mundane stuff. But as the weeks go on, you do your experiments and you read things in the literature and gradually you’re building up a more detailed picture. A new discovery is usually a very tiny thing: one step, one molecule, one interaction. And you spend so long confirming that that's what you've seen — this tiny interaction, a molecule, a step, something new involved in a reaction that you didn't know about, but it slots into this picture. It’s little tiny glimpses of things in between the craziness or the mundane that can fill us with wonder.

How important do you think it is for a scientist to have a passion for the work they are doing?

Absolutely essential. I think, like any demanding career, you need to really enjoy it, to get through the mundane and the difficult stuff, and the things you don't like. Some people really enjoy just messing around in the lab, doing experiments. You almost have to see it like playing, because you have to do a lot of troubleshooting. If you're trying new things, you have to get the experiment working before you can even begin to get data. That's usually the hardest part. You know, you might spend ninety-nine per cent of your time trying to get the experiment working, and then finally, boom! You know, out comes the data and that's it, you know? Tinkering.

You are doing a lot of speaking on this trip in the US.

Yes, and that’s my main bread and butter, communicating to people in churches. I like getting people excited about science. I want them to appreciate that this is a good thing to do, to serve God doing science. I want people to know that there is this great tradition of all these faithful scientists who serve God with their science. And I want to inspire students to know that they can do that. I want to equip them and the church to know that they can be people who love God and love science.

Read more from Ruth at her blog, Science and Belief, and in her book God in the Lab: How Science Enhances Faith.

And your book, God in the Lab?

And your book, God in the Lab?