I want to ask you about being a woman in mathematics. In our

previous conversation, we talked about how you discovered that you really enjoyed math and that you were good at math. I wonder, did you feel any kind of stigma in high school about being a smart girl?

Yes and no. I grew up in San Francisco in the ‘70s and ‘80s. None of my teachers ever, ever, ever gave me the impression that girls couldn't be good at math. In my high school calculus class, over 50% were girls and we were the ones getting the top scores. Certainly none of my classmates ever said anything about girls not being as good at math, but I was aware that there was a societal image of that. I didn't join the math club because that was for nerdy guys.

But I did have insecurities about whether I was smart enough even though I got top scores at Lowell High School. I don't think that would've been an issue for a boy. I also didn't want to tell others my scores because some students got mad at you if you did better than they did. It's not as safe for a girl to be known as smart as it is for a guy. I just kept my scores to myself most of the time.

There's a lot of talk right now about helping girls in middle and high school to think about STEM careers and about how to get them into the pipeline. As you think about the field of mathematics, do you have any words of encouragement or challenge or caution for women who are in grad school and are thinking about giving their lives to math? Is there anything that you know now that you wish you knew in grad school?

First, I would say — be true to your calling. If God's calling you into math, then don’t listen to people who tell you not to do that. Some well-meaning Christians might think, "Why don't you do something useful with your life? Why aren't you helping people?" I didn't struggle when other Christians said that to me. But I did struggle with that idea — why am I not helping feed the hungry?

Or be a doctor, like you were originally thinking.

Right. Spending eight or ten or twelve hours a day just thinking — isn't that a waste of a life? It's not, if that's what God's called you to do.

Second, after finishing my PhD, several people who were not well-acquainted with my past work assumed I wasn’t that smart. At that early stage in my career, I figured they knew better than I did what it takes to do research, so I thought, “Maybe I’m just not really cut out for this.”

But I was cut out for this. It's just that they had preconceived notions of what it looked like to be smart. I did not look or act like their view of a mathematician because I was soft-spoken, afraid to ask questions, and lacked skills in math small-talk or in showing what I know in conversation — all of which are related to the socialization I received as a woman in math.

So, my advice would be — don’t take people's judgment of your capacity that seriously. Look for people who encourage you and who believe in you and listen to them. And by all means follow that still, small voice of God if he gives you a love for the subject, because that is what has kept me going all these years.

That's a challenge, isn't it? Trying to find folks who can help us accurately assess ourselves without bias?

Yes. Another thing — I have seen so many women leave math because of their significant others. I would not recommend moving for someone else. Sometimes it does work out, but I’ve seen way too many examples where this irreparably hurts the woman’s career. I'm not married, so people may say, "Well, you're not going to get married with that view," and maybe that's true. But it's such a risk — I've seen so many women move for their husbands’ work and then they can’t find good jobs in math, so they drop out and do something else. We can't afford that. If you're going to get married, you need to marry somebody who's going to force you to work in math, somebody who says, "Wait. You're gifted. You've worked hard to accomplish this. I'm not going to let you throw this away for me."

And then ask someone to mentor you or at least meet up with you a few times. There are a lot more people who can be encouraging to women now than there were twenty years ago.

And try for things that you don't think you're good enough for. Maybe you don't think you're good enough for a particular job. But you don't know until you try. Maybe you're not good enough for a certain grant. But maybe you actually are, and you just need to try.

Men are much better at this than women, aren’t they?

Yes, they are. And don't turn down any invitations. There have been numerous occasions where I've tried to help women along by inviting them to conferences. They turn the invitation down saying, "Oh, well, I have a friend's wedding this weekend. Or, I had planned a vacation” — this excuse and that excuse. While a friend's wedding is important, if it's not such a close friend and you've been invited to give a talk at a conference, you need to build up your CV. You need to take yourself and your job seriously and not just say, "Well, it doesn't matter that much," because it does. Once you're invited somewhere and you give a talk, if you do well, it gets noticed and you get on people's radars for who's going to invite you to the next set of meetings.

Or if you don't accept the invitation, people will stop inviting you.

That too.

Any thoughts about what you might like to be doing ten years from now?

I’d like to grow a strong and large research group of graduate students and postdocs with the aim of running it in a Christ-like way.

Do you have problems or topics in your head that you would like to have this research group attack?

I don't like “attacking” language. Talking about attacking problems sounds very brutal.

What is your preferred term?

I like to use “solve.” When I work with a problem, I like to bathe in it, sit with it, and be friends — get to know it better.

It's not an antagonistic relationship.

Correct. The problem needs to help me understand it. As far as the future, there are certain problems — I'm building up a supply of different problems that I could work on. I don't have an agenda, but some areas I think it would be interesting for people to work on. Then of course other people would bring ideas, so we would work on those, too. I’d like to lead a research program which would train people to be excellent researchers no matter what they work on: how to be a good citizen, how to treat colleagues with respect, how to go about working on hard problems without letting discouragement stop you, that sort of thing.

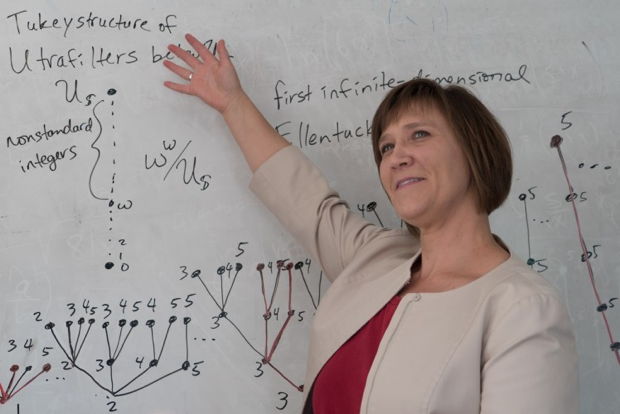

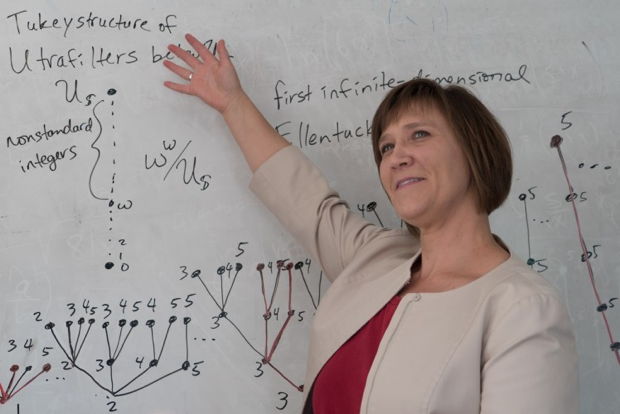

Natasha, thanks for giving us your time. It’s been a pleasure chatting with you and we hope that our conversation and your flowchart will be an encouragement to many. Thanks for sticking it out in a field that has been tough as a woman. I am grateful for you and others who have continued to follow God’s call even when it has been challenging.