Not all of us are able to be at Urbana 2018, so we’re bringing a bit of Urbana to The Well! We are so pleased to introduce you to Anne Zaki, an Urbana plenary speaker. She is Professor of Preaching at the Evangelical Theological Seminary in Cairo, Egypt. We spoke with her from her home in Cairo about her love for God’s word, praying by tree, and reading in grad school at 40.

You can live stream her talk at urbana.org at 7:30 pm central time on December 31. If you’re at Urbana, you can meet her at Women in the Academy and Professions Day in the GFM Lounge — Sunday, December 30 from 2-3 pm.

Tell us a little bit about yourself. Where did you grow up? How did you become interested in the work you’re doing now?

I grew up as a pastor’s kid in a church in downtown Cairo, in a poor neighborhood. My dad was a pastor of a church there for 28 years. When I was 16, I got a scholarship from the Egyptian government to do the last two years of high school at an international boarding school in British Columbia, Canada. There were 200 students from 90 countries. This was my first trip overseas, and an exposure to the world in this tiny school community. It was a great school with high themes for life, training us as young people from around the world for peace and international understanding. It was one of ten schools around the world co-chaired by Nelson Mandela and Queen Noor of Jordan with the concept that peace will not be achieved through political leaders, but by young people knowing each other and learning to co-exist peacefully.

I was a young Christian there. Even though I grew up in the church, I had not really committed to Christ except about eight months before I left for Canada. My head was big, my heart was small, and my spiritual muscles were small. I knew a lot of stuff, but it was waiting to be lived out. At that school I realized that everything I knew I took for granted, and started asking, “Do I really believe this? Or do I believe it just because I grew up in it?” Even what I knew in my head was being sorted and filtered. I gave God a challenge: “If you are who you say you are, and your word is living, prove it to me. I don’t want to be influenced by anyone — not my parents, Sunday school teachers, Christian fellowship, human words, I want your word to prove you are who you are, and I will give you six months, or I will have to start looking for THE living God.” I stopped attending church and youth group, but I did not stop reading the word every day. I was in God’s word every day, looking for God to prove himself. And, he did every single day without exception. There was a clear voice saying, “This is who I am. You haven’t been told lies about me, and what happened eight months ago was for real.”

It was then that I started a relationship with God’s word that’s been solid for me all these years since I was 16 years old. I’m now 41 and I teach preaching based on this foundation: God’s word really can change people even without a messenger. God’s word really has the power to talk to people directly. The power of the word on its own can speak in the same way it spoke to God’s people of old. He doesn’t need a mediator, but he uses them, and I teach people how to be good mediators as preachers. The power of the word on its own can speak. And God speaks. This, for me, was a major foundation for my relationship with the word of God.

I ended up at Calvin College for undergrad with no idea what a Christian liberal arts college was, or where Michigan was. It was a teenage adventure, and I figured if I didn’t like it, I would transfer. I didn’t like it initially, and when I talked to the administration, they told me to change what I didn’t like. That was a big challenge. I thought, “Who am I? I’m a foreigner.” The response was, “That school you went to, weren’t they training you to change the world? This is now your world, change it!” And I thought, “Okay, if you’re making room for me to influence, then I will influence if I can.” I gave myself a semester, and thought if I didn’t make a real impact by the end of the year, it would be time to go.

By God’s grace, the second semester was full of really great stuff; opportunities opened up. I had my first time to preach in English, and they gave me room for that in the chapel — the first time they gave a student a chance. I joined a Bible study, and by the third week, the leader asked me to co-lead a lesson, and from that point on, I had my own weekly Bible study group to prepare for. God was giving me roots in that place, but I was still troubled by the chasm I saw between international and American students, because there was very little global awareness, and I wondered what we could do to bridge that?

I started an arts and culture show of music and dance that we named Rangella — a Hindu word meaning colorful. The show is in the 22nd year, and the income from that show creates scholarships for international students. International students have quadrupled since I was there. The place needed something like this, and the college leadership was courageous enough to give a freshman room to influence an institution. The combination of these two things satisfied a certain need. So, I stayed, my excuses were gone, and Calvin became my home for the next three and a half years. I enjoyed being there and I grew a lot. My time in Canada was about choosing the One who has chosen me, and at Calvin I was learning how to walk with this One. People saw gifts in me that I never thought I would have or considered. It was there that my Christian faith and leadership gifts were cultivated, and my love for the word grew stronger.

I left Calvin and went to graduate school in the American University in Cairo (AUC) for three years for a master’s in Social Psychology. I had married a pastor — a Canadian Syrian who came to Egypt with me. We served our first congregation as youth pastors in an English speaking international church and an Egyptian church, and I was also working as a school psychologist in an Egyptian school in the morning, teaching undergraduate classes at the AUC in the afternoon, and taking master’s classes at night. In year two of our marriage, we had our first son, Jonathan. Those were full years.

At that time, my husband wanted to finish his Master’s of Divinity at Calvin Seminary, which he had put on hold to go to Egypt. We went back to the states for nine months, for him to finish his last year. Meanwhile, 9/11 happened and caused issues for visas with our Egyptian and Syrian passports. Nine months turned into two years and one of us had to work. We weren’t planning on being away for so long, so we had left everything back home. The original nine months ended up being seven years in the US.

In the seven years my husband worked as a pastor, mostly working with Muslim refugees from Iraq, Bosnia and Somalia. I worked at the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship, organizing global conferences and studying the theology of worship in different countries. Meanwhile I did a Master’s of Divinity at Calvin Theological Seminary, and had three more boys, Sebastian, Emmanuel, and Alexander. Those were very full years.

I had my own struggle with my call. I had started a PhD in Christian Education, but then the call to ministry came — but I ignored it because of the women’s ordination thing. I didn't want to be the one dealing with this issue. It’s easier to be a female professor than a female pastor. But God wouldn’t let me off the hook, and after fighting, struggling, reading, and working through it, twelve months later, I decided to go to seminary and quit my PhD. Four years later, still not sure whether I would be a pastor or pursue the academic route, I decided to apply for ordination in the Christian Reformed Church, but later withdrew my application and applied instead to the Presbyterian Church of Egypt, which does not ordain women. I got a very polite letter that said, “Thanks for applying, but the job doesn’t exist.” There was safe distance between us as I was still in North America. We sent polite letters back and forth for two years. “We appreciate your ministry and that of your father and grandfather, but sorry, we don’t ordain women.” I didn’t understand why God was asking me to do this. I was in Canada, why would I be ordained in Egypt? But the call seemed very clear. Every time I pursued ordination in the west, my rest would be dissolved and my peace was gone, and I would find myself writing another letter to Egypt.

Two years later the Egyptian revolution came and with it a revelation. The Arab Spring sprang, and God called us back as a family to Egypt. We wrapped everything up, and the church we were serving in Canada blessed our move. Egypt and the whole region were chaotic; there was fear, but we had peace. We knew this was where God wanted us to be. There was a mass exodus of Christians from Egypt: estimates of 100,000 Christians had left in one year. That’s a lot when you’re a minority. We had seen the church shrinking in Iraq, Lebanon, and Palestine, and we wanted to stop this from happening in Egypt as well or at least to replenish it. For all leaders leaving, we needed to train new leaders. We saw that not everyone could or wanted to leave, and those are the people we wanted to go back and work with. We came back in 2011, and have been here ever since. We didn’t come back to jobs. I stayed at home for a couple of years. There were lots of frustrations and fears, threats of kidnapping, stolen cars. The first two years were heavy and hard, but things got better after the second revolution happened in 2013.

I’ve been at the seminary since 2013 as practical theology professor. I teach courses on worship, preaching, spiritual formation, communication, and psychology. My husband didn’t have a job for the first two years also, as he did a master’s in interfaith dialogue. My ordination quest is still in process ten years later. The polite letters have stopped, because I’m now here. There is no safe distance. They have no idea what to do with me. They are just as confused as I am. They won’t let me be a pastor, but I can be a seminary professor to teach pastors. I can see incredible potential in my female students who are gifted and called. In many ways, I feel that this call has somehow found me, and thus I’m committed to seeing it happen even if it’s not in my lifetime.

Now, I’m doing a PhD at Fuller in preaching. I love God’s word and love preaching. I can’t hide my subversive reason for breaking into an area that has been male dominated, just to confuse things more. I was advised to focus on worship or spiritual formation, but just because I would be more comfortable there doesn’t mean that it is where I should be. Preaching is integrative, it’s a holistic approach to practical theology.

What did you enjoy about graduate school? How do you see your education shaping your vocation?

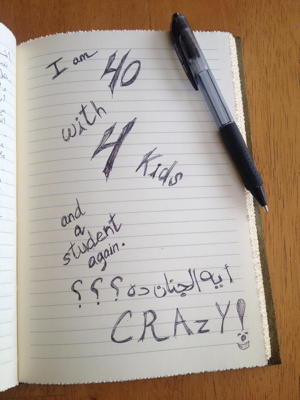

This is my third experience with grad school, and I wish people would wait to grow older to go to grad school. You think you should go when you’re young because you have a better memory, fewer life responsibilities, and more control over your time. You get advised to finish grad school early before family. I did that. And starting grad school again at forty, I found that my memory is not what it used to be. I can sit and read for hours and stay up all night writing a paper, but it takes a bigger toll on me than when I was 22. However, when I read a book for my studies at age forty, it is no longer a book. It becomes a mirror and it becomes a window. It helps me as a mirror to see and understand myself differently. I want to be different. I want this book to shape who I am becoming. I’m not reading to prove myself as a student. I don’t care what people think of me at forty. At 22 I had to prove that I was intelligent and a good academic, that I deserved my scholarship and deserved to be there. At forty, I don’t care! It’s not about impressing the world, but a need to change this world. The church needs us to be different and the world needs the church to be different. My urgency for the call of the church is read very differently.

This is my third experience with grad school, and I wish people would wait to grow older to go to grad school. You think you should go when you’re young because you have a better memory, fewer life responsibilities, and more control over your time. You get advised to finish grad school early before family. I did that. And starting grad school again at forty, I found that my memory is not what it used to be. I can sit and read for hours and stay up all night writing a paper, but it takes a bigger toll on me than when I was 22. However, when I read a book for my studies at age forty, it is no longer a book. It becomes a mirror and it becomes a window. It helps me as a mirror to see and understand myself differently. I want to be different. I want this book to shape who I am becoming. I’m not reading to prove myself as a student. I don’t care what people think of me at forty. At 22 I had to prove that I was intelligent and a good academic, that I deserved my scholarship and deserved to be there. At forty, I don’t care! It’s not about impressing the world, but a need to change this world. The church needs us to be different and the world needs the church to be different. My urgency for the call of the church is read very differently.

I also see a book as a window. I see the person on the other side of the book. Someone studied and put work into this one tiny topic, someone researched, worked and prayed and they came up with serious, thoughtful ideas. It used to be that I would come up with a 90-second response and a smart comment, and then I was done. The challenge now is that I wonder what will be my contribution? When I was 22 during my first master’s and when I was 28 during my second master’s I would be freaking out: I need a plan, I need to know what my thesis is, I need a proposal. Now, I’m much more relaxed about this journey for me and for the church, and I am more concerned for me to be a good contributing member of the church, than for for the church to see me and what I can accomplish.

How do you see your faith and work overlapping?

I’ve never seen my faith and work as disconnected, even when I was in grad school for social psychology at the predominantly Muslim American University in Cairo. I thought Christians would notice, but it shocked me when I heard from Muslim students or colleagues or neighbors that they see the connection and they’re able to name it. They’re able to see the cause behind my life.

When I teach well in Psychology 101, I’m doing this not because I’m a good citizen of Egypt or because I have a good conscience and want to justify my pay. They see and they name that you are a good teacher because of your faith. For somebody who didn’t grow up with a world view that integrates faith and work, for them to articulate it that way means one of two things: either the articulation slips out without me noticing it and they’re echoing what I’m saying, or there really is a God that shines a light in the darkness — or both. I’m not excluding one or the other. It always surprised me. It’s like your Chinese neighbor suddenly speaking in Spanish because they’ve been hearing and seeing Spanish for a while. They may not know fully what it means, but they’re hearing and repeating the words. Those words may someday sink in and do something, and the meaning will be so attractive to them that they’re unable to resist it.

Growing up as a minority in a primarily Muslim country where you're not allowed to evangelize, the only way to evangelize without being arrested was our lives. There is no alternative. You can’t speak, you have to live. Silently, but loudly. This practice of living silently but loudly is what guided my worldview throughout. Going to college and learning about the reformed tradition integrating faith and learning, was the first time someone gave me language for everything I lived. I’m grateful, and I give credit to people who raised me in this tradition. It wasn’t a catechism class, it was simply, if you’re going to be a Christian in this culture, in this country, this is how we live so the church won’t die. Then the language gave articulation to the life, and now the life in turn articulates in word and deed.

What’s a spiritual practice you have found meaningful or would advise to women in the university?

In this season, it has been challenging. In grad school we read so many books! Every week! And you’re supposed to have a good idea of what they’re saying. I discovered weeks in to my program that when I pick up the Bible to read, it’s become another book. I’m studying it, instead of letting it study me. It stopped being the way God communicates with me, and it became a task in which I ask: “What’s the general idea?”

That was very frustrating to me. By God’s amazing provision, just before I started grad school, I was at a conference in Texas, where I met a young African American woman who gave me a flashlight. This flashlight had the Bible recorded on it in English, in Arabic, and in colloquial Egyptian Arabic. [Literally — this is a solar-powered flashlight and audio Bible combo.]

I took it, and it stayed in its box until one day I was walking to Fuller and thought, “This is crazy, I just did my devotions and I can’t remember what it was on. I don’t remember a word, not even the passage. What am I doing? This has become a dead routine.” It hit me that I have an audio Bible, and a one-mile walk every day. Why not use this time to be in the word differently?

So, for the past year and a half, I have not been reading my Bible except to prepare sermons. Instead, I’ve been listening to the Bible. It’s incredible. It’s dramatized, and I find myself talking to the characters. I hear what Sarah or Rachel did and I’m like “Oh come on! Don’t do this!” I’m engaging the story as if it’s a drama unfolding in front of me. Listening to Scripture has been an incredible spiritual discipline for me. I’m an audio learner, so I’ve been able to unconsciously memorize verses as I hear them. I walk every day, and I listen to it all the time. I’ve gone through the Bible quite a few times. My house is quiet, and I’m used to a busy, noisy house, so I let it run while I’m cooking or cleaning. It has become the soundtrack of the last year and a half.

I didn’t anticipate the memory piece, and I didn’t anticipate that the word of God would lead me into prayer. I usually separated those. I spent time to read, and then I would pray. The audio part has made everything interwoven. As I’m listening, I’m thinking of certain people and praying for them. I got this idea of turning my walk to Fuller into a prayer walk.

As I’m listening to Scripture, I name certain trees, light poles, and traffic signs after people I need to pray for daily. And then I have a random stop sign for people who need prayer on a certain week. This spiritual discipline keeps me on track. If I don’t have these visual concrete reminders, I’m afraid that I’ll forget to pray for other, and I won’t be a good pastor, a good shepherd. I cross the highway that has eight lanes one side and eight lanes the other. Each lane is for one of my kids, one for my husband, one for each of my parents. On the other side, I pray for cities. Los Angeles and Cairo always first two lanes — the HOV lanes. They’re both fast moving cities and they need lots of prayer.

These have been good disciplines for me. The audio Bible and prayer walk have become my versions of spiritual disciplines, keeping me healthy and sane in this season of my life.