This article was originally posted on the BioLogos Forum.

I was so happy, nestled on a couch between two good friends at our church’s annual women’s retreat. The speaker was describing a biblical approach to counseling. In particular, she emphasized our gifts as women for helping and nurturing. “We are life givers,” she said. “This goes all the way back to the Garden. The world wants to remove distinctions between men and women, and to remove our status as image bearers.” Amen, I thought. “Our story is that of Creation," she went on. “What’s the world’s story for how we got here?” “Evolution!” a chorus of voices replied. I sighed and made eye contact with another biologist in the group. She looked like I felt — disappointed.

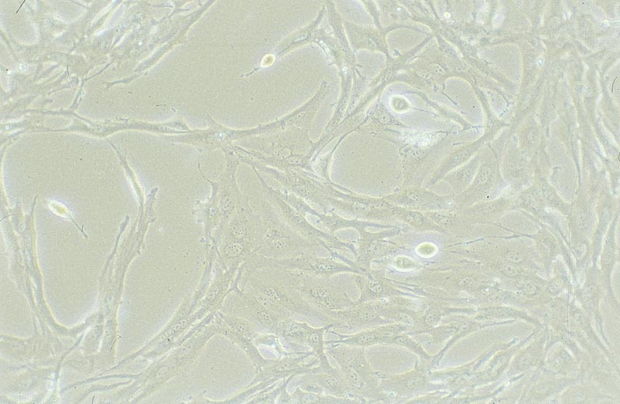

Human cells magnified under a microscope.

I love my church. I love the high view of Scripture and worship that our leaders maintain. I love the emphasis on living in community and serving our world. I am grateful that even though my view on origins is different from that of my pastor, he and the rest of the elders have supported me over the years as I have sought to reconcile science and theology. Yet as my retreat experience shows, it is not always easy to be a biologist in a Bible-believing church. I think it would even be harder to become a Christian if you were a biologist confronted with such an environment.

Building a Stronger Foundation for Faith

I haven’t always accepted evolution. In fact, for a long time I didn’t want it to be true. All I knew was that it seemed to be a creation story for non-Christians. It’s true that there are many who use evolutionary science to support an atheistic worldview. But I’ve come to understand that this is by no means a necessary outcome of understanding the science.

I grew up deep in the heart of Texas, which in turn is deep in the heart of the Bible Belt. As a kid, I loved studying nature and could usually be found climbing trees, catching butterflies, or looking at all manner of things under my grandfather’s old microscope. I also loved God and the Bible. I came to faith in Christ at summer camp when I was nine and spent much time memorizing Scripture and attending church with my family. I even repeatedly shared the Gospel with my dog, Tuffy, because Jesus surely died for her sins, too.

As a teenager I thought deeply about matters of science and faith. Once I presented my dad with a list of Big Questions ranging from “What’s on the other side of a black hole?” to “What activities are there in heaven?” But when I went off to college, I wasn’t prepared for the onslaught of new ideas that would challenge my faith. Centenary College, in Shreveport, Louisiana, is a true gem of the South — a small liberal arts college with a Methodist connection. It was a rich intellectual environment, and there were many opportunities for fellowship with other Christians. But like many college students, I found it all too easy to avoid serious commitment to any congregation or campus ministry group, and this “untethering” made me feel rather lonely in my faith walk.

In my freshman year I took a Bible survey class and learned about other ancient creation stories that were eerily similar to the early chapters of Genesis. Also there were lots of other mysterious writings that weren’t included in the New Testament — the early church had decided which books to include. And there were loads of textual inconsistencies I’d never noticed before. How could I have never heard about these things? It had never occurred to me to ask how the Bible had come to be and how we could still say this is God’s word when there was clearly so much human intervention. With no resources to work through these things, the very foundation of my faith seemed to crumble. Meanwhile, many of the Christians I knew seemed either anti-intellectual or hypocritical — myself included. I continued to read my Bible every morning and go to church most weeks (often sitting in the back row, analyzing everything I heard with paralyzing skepticism), but I had serious doubts about Christianity.

I set out to major in biophysics and eventually added a math major as well. I was good at science and loved the elegance and beauty of it. But I avoided the one area I felt might drive a nail in the coffin of my weak faith — evolution. One biology professor on campus was an open advocate of evolution and Darwin. I am ashamed to say that it occurred to me more than once that she might be the Antichrist.

In the last semester of my senior year, the Lord gave me a gift. I began to attend a Bible study at the home of a young professor in the English department. She and I met regularly over coffee. I grilled her with four years of unanswered questions. She was the first person I met who displayed both a deep love for Christ as revealed in the Bible and a passion for scholarship and rigorous thinking. Through her, God worked powerfully in my life to restore my faith.

Becoming an Evolutionary Creationist

With a voracious appetite for theological and scientific knowledge, I arrived in California for graduate school in biology. I joined a computational cell biology laboratory focused on studying the dynamics of the cell’s internal scaffold, the cytoskeleton.

While my work was not directly focused on evolution, the topic was everywhere around me, just as creationism was part of the culture of the South where I grew up. Confronted almost daily by my ignorance of the science of evolution, I decided to embark on a study. I was confident that if Christianity were true, it could withstand even the toughest questions. And if it couldn’t, I didn’t want any part of it.

So, I set out to read a series of books from multiple perspectives. In 2006, world-famous geneticist Francis Collins published The Language of God, in which he described his radical conversion from atheism to Christianity and laid out a number of compelling lines of evidence for evolution. My heart filled with joy as I turned the pages and saw so many things falling into place. It didn’t answer all my questions (and the more I learn, the more questions I have), but I found a place of rest, both mentally and spiritually. This was another gift from God.

In the coming months I connected with others who shared Collins’ evolutionary creation perspective. They loved science because it revealed the secret workings of God’s good creation and helped them worship God better. But they also loved the Bible and didn’t try to gloss over the difficult parts. And most importantly, they loved Christ’s church, despite what her members were saying about scientists. I felt like I had come home.

Open Questions

Several years later, I still have lots of questions; some are about science and some about theology and biblical interpretation. For starters, I am unsure of the extent to which natural selection acting upon random mutation drives evolution. This is a hotly contested question in evolutionary biology. Many Christians might be confused by this, since we so often hear scientists claim that “evolution is a fact.” What is not contested is that all the diversity of life of earth, including humans, shares a common ancestry. To be sure, many relationships have yet to be worked out. But it seems undeniable, especially given recent genetic evidence, that humans share a common biological ancestor with other species. However, the specific physical processes driving evolution are still under investigation.

Common ancestry of humans with other species raises immediate questions of biblical interpretation. Doesn’t acceptance of evolution require rejection of the Genesis account of human origins? Indeed, it is hard to reconcile evolution with the traditional understanding of Adam and Eve as the first and only parents of the human race. But evolutionary science is silent on whether Adam and Eve were historical figures; it merely states that there was never a time when just two people roamed the earth. Perhaps Adam and Eve were the first two people with whom God began a relationship? In the fullness of time, he called them out for a purpose, just as he did with Abraham, Moses, David, Elijah, and pretty much everyone else in the Bible. God made a covenant with Adam and Eve, which they broke when they fell into sin. As our representatives, their sin became our sin.

I am aware that many Old Testament scholars, even conservative ones, feel there are good reasons to think Adam and Eve were not historical figures. I respect that. I don’t think the Gospel hangs in the balance, whatever the case. Christianity depends on the historical life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, whose sacrifice on the cross redeemed us from our sins.

I also have questions about deep time and suffering. Humans have been around about 200,000 years, which sounds like a long time until you consider that the universe is 13.8 billion years old. What was God doing all that time before we existed? I don’t know, but I suspect he was delighting in his good creation. And what exactly does Paul mean in Romans 8 when he says that the creation was subjected to futility and groans for the revealing of the sons of God? It is hard for me to attribute all pain, death, and suffering to humanity’s fallen state (as many Christians do) for two reasons.

First, physical death has been around since the dawn of life on earth, long before humans existed. And part of our creation mandate — given before sin entered the picture — was to subdue the earth (Gen 1:28). The need for “subduing” implies some amount of natural disorder existed in the beginning.

Second, while death is surely our enemy to be vanquished in the end, the Bible often describes death and suffering being used to serve redemptive ends. Jesus declared that a man wasn’t born blind because of anyone’s sin, but “that the works of God might be displayed in him” (John 9:3). Paul says we must rejoice in our suffering, because suffering produces endurance, character, and hope (Rom 5:3-4). Indeed, “this light momentary affliction is preparing us for an eternal weight of glory beyond all comparison” (2 Cor 4:17). And most importantly, the cross of Christ was not some cosmic cleanup job, a Plan B devised when humans first sinned; it was ordained from the beginning (Acts 2:23). I can’t begin to understand all this, but it is clear that “all death is the result of sin” is too easy of an answer.

As I see it, evolution is an elegant and beautiful means by which the earth brings forth living creatures (Gen 1:24) under God’s providential hand. The idea of sharing an ancestor with a chimpanzee doesn’t offend me in the slightest. Rather I am humbled when I consider that God chose us from all his creatures to bear his image and become his sons and daughters. I look forward to the day when Christians will worship the awesome God of creation without rejecting the testimony of his works revealed in the fabric of the created order.