The old man roused himself. “What is it now?”

“Oh sorry,” Jack said. “Sorry. It’s Tuscaloosa. A colored woman wants to go to the University of Alabama.”

“It appears they don’t want her there.”

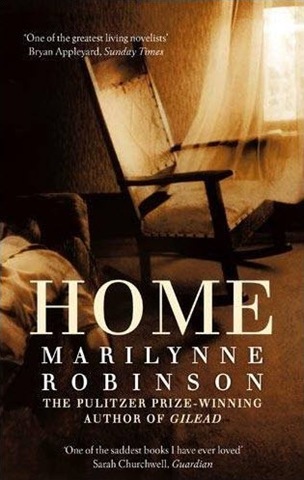

I listened to a recording of Marilynne Robinson’s Home this fall as I drove from my home in Fort Wayne, Indiana, to a conference in Kentucky. I’m a fast reader — too fast sometimes — and audiobooks, slow and measured as they are, are not a habit of mine. I found myself impatient as I longed for the characters to just speak truth to one another and repair their broken relationships. But as I listened over the hours, I was glad for the sometimes painfully slow conversations. Just like it is in my world, truthfulness and healing were slow going, sometimes unattainable.

I listened to a recording of Marilynne Robinson’s Home this fall as I drove from my home in Fort Wayne, Indiana, to a conference in Kentucky. I’m a fast reader — too fast sometimes — and audiobooks, slow and measured as they are, are not a habit of mine. I found myself impatient as I longed for the characters to just speak truth to one another and repair their broken relationships. But as I listened over the hours, I was glad for the sometimes painfully slow conversations. Just like it is in my world, truthfulness and healing were slow going, sometimes unattainable.

Home, the second book of the Gilead series, tells the story of the return of Jack, old Boughton’s prodigal son, to his small hometown of Gilead after twenty years away. Jack is checking out the territory. And though he doesn’t say it directly, he’s feeling out the possibility of bringing his black wife and son to Gilead, to live as a mixed-race family. He probes in slow-as-molasses conversations. His father doesn’t know about the marriage or the child.

Boughton, Jack’s father, is a good man. He has raised his family, pastored his church, and been a steady friend. He isn’t the evil hypocrite masked in religion found in novels like The Poisonwood Bible. So his comments about race made me cringe. I wanted his faith to be bigger, his morality to include the oppressed. I was rooting for him.

“On the screen white police with riot sticks were pushing and dragging black demonstrators. There were dogs.

His father said, “There’s no reason to let that sort of trouble upset you. In six months nobody will remember one thing about it.”

For old Boughton, as for Gilead, the events in the south, in Selma and Montgomery, are distant and irrelevant. Though the town was founded by abolitionists, the black church was burned down years ago. And now it’s a sundown town — blacks must leave by nightfall.

When I watched Selma last month, John Legend and rapper Common’s “Glory,” became the soundtrack in my head for days.

One day when the glory comes, it will be ours.

One day when the war is won, we will be sure. We will be sure.

I had read about the passage of civil rights legislation in An Idea Whose Time Has Come: Two Presidents, Two Parties, and the Battle for the Civil Rights Act of 1964. I gained an understanding of the complexity of legislation, of the complicated interplay of personalities and interests. There is a fierce struggle in politics between self-interest and the greater good.

In the movie, I was shown the inner working of the Southern Christian Leadership conference over the three-week period they spent in Selma, Alabama, leading up to the march to Montgomery. As I watched, I was humbled by both the tedium and cost of justice work. There is planning and strategy, organizing and making sandwiches. There is the physical toll on families and individuals. Sometimes there is physical violence and death.

Jack asked his father if he thought the long-term consequences of the violence in Montgomery would be important, and his father said, “I don’t believe there will be any consequences to speak of. These things come and go. The gravy is wonderful by the way.”

I’ve been struck lately in the book of James, by the way he turns the way I see people upside down, like Jesus does. For James, the rich are oppressors, busy laying up treasures, indulging in luxury. The poor are elevated. James says faith without works is dead. I used to think that works were the nice things we did for one another, the non-sinning parts, but examples James writes of are works for justice, feeding and clothing the poor, visiting orphans and widows.

James doesn’t write about marching or political activism or working for legislation, but he was writing in a context that did not allow for these freedoms. Given our freedom to act and speak and protest, I will let James’ words speak to what I am free to do in this time and place.

I don’t have a roadmap for this. I’m a writer with a family, a job, and a master’s degree in process. I’m also still finding my feet in the US after being overseas for nineteen years.

When we lived overseas, justice issues were unavoidable. In France, we lived in a city where I saw the homeless every day, where refugees needing practical help turned up at our church.

My life here in the Midwest is different. Though my job takes me into the city, without it I could easily stay sheltered from the realities of injustice, the poor, and those in need. I could get very focused on my gravy.

I have access to information, but at a distance. I cannot hold victims of Boko Haram in Nigeria, dead Parisian journalists, the families of the Chapel Hill students, the victims of ISIS, and of Tamir Rice all in my heart, much less actually do something about each one. I’m not facing it when I walk out my door or go to church. I have to be seeking out my involvement intentionally.

For my family, works has looked like showing up at our city’s Martin Luther King Day celebration and clapping for young people who sang and danced on the stage, and processing the experience with our daughter afterward. It’s looked like writing a note of condolence and peace to a Muslim colleague potentially jarred by the events at Chapel Hill; meeting with Muslim students on campus and discussing their fears; having an open conversation about race with a friend of a different color.

Works have also been my words on the page, processing what I see and hear, how I think and act. I don’t want to be old Boughton, not letting the events of the day trouble me, just thankful for my portion of gravy.

I don’t want the church to not be troubled either. Twenty, forty, fifty years from now, will someone examine our words and silence, our action and inaction in the face of the realities of our world and wish that our faith had been bigger, that our morality had enough room to care about justice for all?

I’m rooting for us.