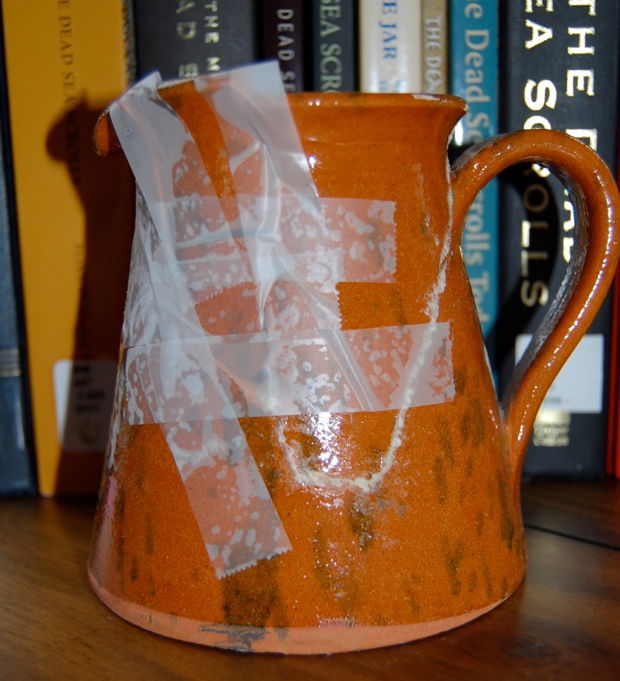

My son has a temper. Some say the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. Six months ago my son in his rage hurled a toy at a pitcher of mine, sending it crashing down into shards. And this wasn’t just any pitcher. A beautiful, simple, terra cotta piece, it was a reminder of a trip overseas a decade ago. I tried to repair it with high-tech glue to no avail. It has been sitting on a shelf, in pieces, for months. Unable to return it to its ideal state, I gave up.

Idealism, though, is a killer of joy. In this season of preparation and joy, I am reminded of my constraints. I have not reached my hoped-for deadlines for research and writing. And I can tend towards a downward spiral when I fail, which runs the gamut from anxiety to guilt to regret to doubting my call. My call.

It’s simple to say that I’m called to teach. Or I’m called to be a professor. Or I’m called to equip people to read the New Testament in its historical context. And I believe those are true assertions.

But, I am also called to finish my research paper on the Qumran community and to be present to my children this Advent. These are also true.

Kate Harris of the Washington Institute for Faith, Vocation, & Culture spoke at Q: Women and Calling recently. She reminds us that the concept of “calling” as something to be realized in the future, a potential often separated by many intervening steps, is too narrow. While we may have long-term goals for how to exercise our gifts or fulfill our passions, calling does not refer to a distant dream alone. Indeed, we must live out our call today. Now. In the present.

A shift in our concept of call brings our constraints into focus — all of the reasons we cannot fulfill our dreams at present. We lack the time, money, or resources to pursue them. As one who senses a call to teach, I become frustrated with how long my current degree drags on. My circumstances require research and writing to fit into the margins of my weeks instead of in the center. I can grumble that it’s impossible to attain my calling at a snail’s pace.

Yet Harris reminds us that our calls are present in our limitations. In the limits we experience, choices are made for us. And, as Barry Schwartz describes in The Paradox of Choice, that’s a good thing. Limitless choice is paralyzing. In the midst of our constraints, we move forward with creativity. Instead of yearning for different circumstances, we can be sure that God is still calling us right where we are.

Another correction Harris gives for our definition of calling relates to where we discover it. Much has been written about discovering our gifts, particularly in recent years as the positive psychology movement has exploded and resources like StrengthsFinder have been adopted widely in both corporate settings and in local churches.

But Harris says that we are looking in the wrong places. It is not merely our gifts that determine our callings. Often our callings stem from our grief or our brokenness. God’s call may lead us to work that will heal our own wounds or that will use them to bring healing to others.

As I reflect on the desire to teach and the hopes bound up in that, my passion is certainly related to the ways in which I have been hurt in the past. And yet, my hope is to bring healing to others who have had painful experiences similar to mine.

Last week, these lessons came into focus. My son and daughter rounded the corner with a surprise. They beamed as they showed me the pitcher—its pieces once again forming a whole. The entire vessel was covered in scotch tape. “We wanted to fix this for you because we knew you hadn’t gotten around to it, Mama.” It now rests on my bedside table, a parable and an encouragement.

We are like my pitcher. We are cracked and cannot seem to glue ourselves back together. We are wounded, broken, and limited. We are not perfect — far from it. Yet we are called now, in the midst of the messiness. Instead of imagining our callings like a perfect, beautiful, whole pitcher, an ideal that we will not attain, let’s live out our callings more like my pitcher: cracked and imperfect, but redeemed by loving hands. And unlike the little hands that taped my pitcher together, God’s hands are able to redeem our cracks and make us truly whole.