Ah, Christmas, the season of contradictions! For many, this time of peace and hope is marked by frenetic schedules teetering on the razor edge of chaos — almost a Christmas tradition itself! We all know the list: buy gifts, send cards, attend events, make food, travel, host family and friends, clean for said guests, decorate, and on and on. And for those of us whose lives are as tied to the academic calendar as the church’s, there is the added pressure of wrapping up the semester. The sad truth is that the contemplation of God’s miraculous, bodily entrance into human history must vie for mental space with department meetings, research deadlines, and grading of epic proportions.

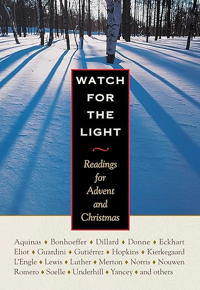

I have found that the effort to push back against the avalanche of distraction takes some intentionality. Over the years, I have benefited from various practices and devotionals to carve out time and realign my brain in a daily way in an effort to preserve Advent as a season of Christ-focused anticipation. Among the best of these has been the compact volume Watch for the Light: Readings for Advent and Christmas (Plough Publishing House, 2001), a gentle resource that provides an entry for each day, beginning at the end of November and carrying all the way through Epiphany on January 6. Because these are a collection of various authors’ works, each stands alone, and there is no sense of disjointedness if a day is missed. Even used in a weekly or occasional fashion — or whatever configuration is accomplishable amid competing personal and vocational demands — there is much richness that still can be gained, a grace we can all use.

More so though, this broad representation of writers, thinkers, theologians, poets, mystics, and philosophers brings breadth, depth, and heft to a season where we as individuals and in community struggle to stop to linger long on the unfathomableness of God with us. The writers traverse centuries and geography. Bernard of Clairvaux sits comfortably next to Philip Yancey and Søren Kierkegaard. Bible translator J. B. Phillips warns of the struggle with complacency and passivity in the “Dangers of Advent,” while Madeline L’Engle calls us to marvel that “[e]ach galaxy, each star, each living creature, every particle and subatomic particle of creation . . . are all children of the Maker.” Italian apologist Romano Guardini, German mystic Meister Eckhart, American journalist and activist Dorothy Day, Peruvian priest and “father of liberation theology” Gustavo Gutiérrez, and British academic, prolific writer and apologist C. S. Lewis — all speaking from their time and place ponder the timeless mystery of the “Grand Miracle.” They invite us to consider what it means to wait, to make room for Jesus, to yield to God. They offer meditations on being inhabitants of the “visited planet,” on being “shipwrecked” before Christ, on being receivers of Good News — the “original revolution.”

More so though, this broad representation of writers, thinkers, theologians, poets, mystics, and philosophers brings breadth, depth, and heft to a season where we as individuals and in community struggle to stop to linger long on the unfathomableness of God with us. The writers traverse centuries and geography. Bernard of Clairvaux sits comfortably next to Philip Yancey and Søren Kierkegaard. Bible translator J. B. Phillips warns of the struggle with complacency and passivity in the “Dangers of Advent,” while Madeline L’Engle calls us to marvel that “[e]ach galaxy, each star, each living creature, every particle and subatomic particle of creation . . . are all children of the Maker.” Italian apologist Romano Guardini, German mystic Meister Eckhart, American journalist and activist Dorothy Day, Peruvian priest and “father of liberation theology” Gustavo Gutiérrez, and British academic, prolific writer and apologist C. S. Lewis — all speaking from their time and place ponder the timeless mystery of the “Grand Miracle.” They invite us to consider what it means to wait, to make room for Jesus, to yield to God. They offer meditations on being inhabitants of the “visited planet,” on being “shipwrecked” before Christ, on being receivers of Good News — the “original revolution.”

With each entry — be it a poem or sermon or essay — the opportunity is given to approach familiar stories and truths with a sense that something new is yet to be gleaned, to view Advent and Christmas not only as accomplished historical events but the ongoing, always-arriving transformational power of God. In the essay “Annunciation,” American novelist Kathleen Norris explores how this announcement was not merely to be received but demands a response — certainly from Mary in her awe-filled obedience, but also from us. Norris suggests the idea of being “virgin” extends beyond Mary’s physical, biological state but also is reflected in her simple “Here I am,” devoid of arrogance and embedded in holy fear and wonder. Norris asks, “When the mystery of God’s love breaks through into my consciousness, do I run from it? Do I ask of it what it cannot answer? Shrugging, do I retreat into facile clichés, the popular but false wisdom of what ‘we all know’? Or am I virgin enough to respond from my deepest, truest self, and say something new, a ‘yes’ that will change me forever?”

Similarly, T. S. Eliot’s poem “The Journey of the Magi” seeks to replace our images of the carved gilt figures of nativity sets or little boys in bathrobes and cardboard crowns with something realer and more true. As much imaginative prayer as poetry, Eliot’s magi have “a hard time of it,” traveling through towns and cities that are hostile and unfriendly, “villages dirty and charging high prices.” Their exhausting search for the Christ Child contains echoes of our own sometimes weary seeking: “At the end we preferred to travel all night, / Sleeping in snatches, / With the voices singing in our ears, saying / That this was all folly.”

But Henri Nouwen affirms that we are not alone in our seeking or in our traveling through a sometimes hostile world. In the November 28 entry “Waiting for God,” Nouwen reshapes the parameters of Christian community often restricted to Christmas Eve services and holiday gatherings into the very means by which we are allowed to be “people who can live in a very chaotic world and survive spiritually.” He offers that the great gift of Christian community is “a space in which we wait for that which we have already seen.” Waiting together in community “is how we dare to say that God is a God of love even when we see hatred all around us. That is why we can claim that God is a God of life even when we see death and destruction and agony all around us. We say it together. We affirm it in one another. Waiting together, nurturing what has already begun, expecting its fulfillment — that is the meaning of marriage, friendship, community, and the Christian life . . . We need to wait together to keep each other at home spiritually, so that when the word comes it can become flesh in us.”

Like all great writing and thinking, the entries contain the wisdom of the ages while maintaining (almost eerie) relevance for today. Jane Kenyon confronts the reader in her poem “Mosaic of the Nativity, Serbia, Winter 1993” with the question “so what does it matter now / if we shell the infirmary, / and the well where the fearful / and rash alike must / come for water?” Twenty-one years later Gaza, Ukraine, Sudan, Syria, Democratic Republic of Congo pose the same disheartening thought. In 1970s Nicaragua Padre Ernesto Cardenal recorded a congregational discussion about the wise men and their decision to go to Herod the elder looking for the Messiah. The transcript is the entry for January 3 and reveals with candor a realistic understanding of the political terror and repression under which Jesus was born. As one young man shared regarding Herod, “He must have felt hatred and envy. Because dictators always think they are gods.” The violence and oppression Somoza inflicted on the Nicaraguan poor in the 1960s and 1970s was true of Herod thousands of years before and true of Putin and the other despots of our current milieu. But far from being hopeless, the insightful response of another Nicaraguan congregant describes the paradox that can still confound, frustrate, inspire, and mystify us today: “Those wise gentlemen found something they weren’t expecting — that the liberator was a poor little child, and besides, a little child persecuted by the powerful.” These readings are weighty but in the best possible way. Not despairing or unnecessarily didactic, they are wonderful reminders that even as we hygge-up our earthly homes we are actually citizens of an entirely different kingdom and our eyes should always be on the horizon watching for the great light that has dawned on people walking in darkness.

Whether one’s holidays are marked by the warmth of friends, family, and festivities or are a season where the normal burdens feel heavier or some unwieldy combination of both, it is undeniably helpful to pause even for a few moments amid the tumult. It is helpful to be reminded that whatever occupies, or preoccupies us at a given moment — be it a dissertation nearing completion or a charcuterie board for a party or the most challenging family members on the planet — there is a joy and a hope that is not fettered by this world and its ways, and the unfolding wonder of what one day will be has already begun.

Perhaps the title alone — Watch for the Light — points to the sense of expectation and reprieve this book offers. Because so often hiding behind the exuberant carols and twinkling lights is a very real darkness — the darkness of feeling overwhelmed and adrift, of empty materialism at the expense of the exploited and oppressed, of a world on fire and seemingly at the mercy of the corrupt. The darkness of the human heart that necessitated God’s interruption of our headlong course toward destruction with the appearance of a tiny baby who is the Light of the World. Each entry offers the reality of the Incarnation, the hope of the Kingdom inaugurated, a tug away from darkness and into marvelous light. They speak to the homesick longing God has planted in even the most agnostic heart, the hoped-for respite from fear and total neutrality that Sylvia Plath glimpses as she treks “through this stubborn season / Of fatigue” in “Black Rook in Rainy Weather” (November 25). This poem — this book — appeals to us to pause, to watch, to contemplate, and to anticipate once more that,

Miracles occur,

If you dare to call those spasmodic

Tricks of radiance miracles. The wait’s begun again.

Photo by Bonnie Moreland on StockSnap