"Indeed, you have comforted me and spoken to the heart of your servant-girl." Ruth 2:13, from Who are you, my daughter? Reading Ruth through Image and Text, Ellen F. Davis & Margaret Adams Parker, Westminster John Knox, 2003. Reproduced with permission of Margaret Adams Parker.

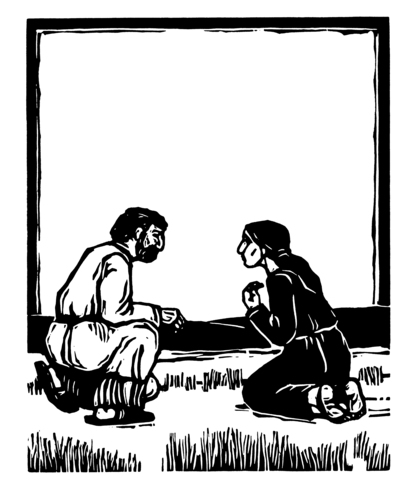

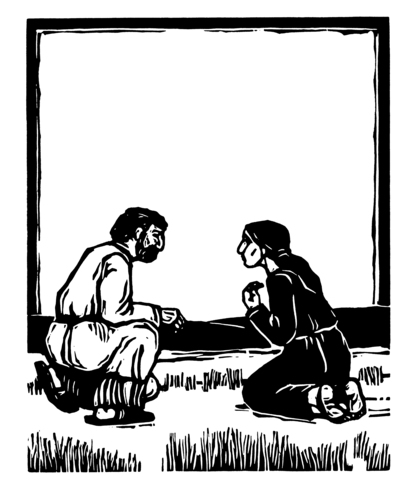

Spend a moment looking at this woodcut by Margaret Adams Parker from the story of Ruth. What do you observe? What questions does the image raise? Allow yourself to wonder. We’ll return to this piece a little later. First, let’s talk about how art can enhance our understanding of Scripture.

We often think of art as self-expression, but art encompasses more than this as well. Much like language, art operates on the principle of metaphor to express ideas that may be emotional or intellectual, abstract, or concrete. “Expressiveness is grounded in fittingness,” explains Nicholas Wolterstorff in his book Art in Action. In this theology of artistic practice, he highlights the function of reasonable comparison in symbolic expression. This is how metaphors work: a metaphor invites a comparison between certain like qualities of two unlike things, thereby expressing whatever quality is being compared. (Read more in Wolterstorff's book, pp 112-116.) Phyllis Trible puts it another way, saying that metaphor suggests “semantic correspondence” between a familiar object and a less familiar object. Placing the objects in parallel to one another asserts a meaningful similarity between them so that we can understand the less familiar in terms of the more familiar (“Clues in a Text,” p 17).

We are familiar with verbal metaphors: “Life is like a box of chocolates” (Forrest Gump). The objects for comparison are similar in some ways; life and a box of chocolates are both varied, surprising, and frequently delightful. But they are not similar in every way; life is not made of fermented beans and sugar! Moreover, “life” is a complex, abstract idea. Saying “Life is like a box of chocolates” concretizes that idea so that we can understand and contemplate a particular aspect of it — the part of its meaning that is similar to “a box of chocolates.”

When an artist comments on Scripture through a nonverbal medium, she layers textual details with the elements of her medium. By presenting words from Scripture together with a visual, auditory, or kinesthetic “object,” the artist suggests that a comparison can reasonably be made. The task of the observer is to discern that comparison, and there may be multiple ways to do so.

Let’s return to our example, the woodcut print of Ruth 2:13 by Margaret Adams Parker.

Parker explains why she depicts Boaz in this posture: “The text describes both Boaz and Ruth as ‘valorous’...Boaz and Ruth are fit partners, equals. So I picture Boaz, in the first meeting with Ruth in the fields, crouching down as he speaks with her. We might have expected him to stand or bend over the kneeling woman. It is a measure of character...that he instead lowers himself to speak with her.”

The artist herself points out that the text uses the same word to describe the character of both Ruth and Boaz. In creating a woodcut to represent the first scene where they appear side-by-side, she uses the spatial metaphor of vertical levelness between them to express an idea that the text expresses verbally (but also indirectly), which is that Ruth and Boaz are equals. There is fittingness between Parker’s spatial metaphor and the text’s verbal expression because both indicate congruence between the two characters.

Interpreting Scripture through art brings new insight to the fore through comparisons between textual details and elements of the artistic medium, as shaped by the artist. It also invites the viewer to draw out further insights based on the layers of comparison that their unique perspective brings to the art, making artistic interpretation of Scripture a communal practice.

When I look at Parker’s woodcut after reading the whole book of Ruth, I see another metaphor: a comparison between Boaz’s movement towards Ruth and Jesus’s incarnation. In the preceding woodcut of Ruth 2:5, Boaz stands on a hill looking down at Ruth in the field. When he comes down to crouch beside her in this woodcut of Ruth 2:13, he initiates a relationship of redemption by spatially stepping down from his place of authority and entering Ruth’s sphere of loss and labor. The movement between these two images highlights the way Boaz uses his power to favor the person conventionally considered beneath him, in the same way that Jesus steps down from his position of equality with God to take on the form of a human and suffer for our redemption (Philippians 2:6-8).

Over the next few months, you will find at The Well a series of pieces each created to guide you through a meditation on a passage of Scripture through a work of art. The guides direct your attention to aspects of the artwork that highlight ideas found in the Scripture, and we hope they help you gain insight into the biblical text. For the writers and artists who penned these reflections, insights into the meaning of the text were discovered through the art, whether in the process of making or in observation. Attention to the visual, auditory, and kinesthetic details of the artwork translates into attention to the verbal details and literary patterns found in the text, and this communication between art and text — an assertion of fitting comparisons — makes the artwork useful for interpreting Scripture.

As you engage with these pieces, think of the artwork as a lens through which you see the text. Each medium — music, dance, oil-on-canvas — has unique tools at its disposal which bring particular elements of the text into sharper focus. The writers share which elements of the text the art brings into focus for them, so after you read their interpretation, consider the piece through your own lens and see what it brings into focus for you. Each piece will also include a prompt for journaling and creative reflection that you can use to continue engaging with God through the text at hand. If you try any of the response prompts, please share your reflections and creations on social media and tag us! That way we can engage these pieces of art and Scripture communally.