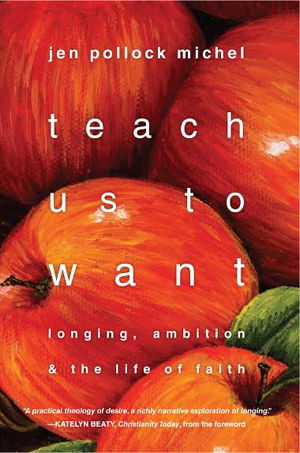

Thank you so much for having me, Joanne and InterVarsity Christian Fellowship. So my name is Jen Michel. I'm speaking from Toronto, and I'm envious of those of you who are calling in from California. But today I want to talk to us about desire in the context of faith. And whenever I tell people that I've written a book about desire in the context of faith, I get that really weird look, like, "Huh?" Like, "Desire doesn't belong in the context of faith." And I think that's actually exactly the tension that I want, where I want to go today, and where I've gone in the book, "Can desire belong in the context of faith?"

I think central to our hesitation about desire is this question that I want you to be thinking about as we talk today. Can we be trusted to want? Can we be trusted to want? We know that we should desire God. And that's given to us in Scripture, verses like Psalm 73:25: "Whom have I in heaven but You? And there's nothing on earth I desire besides you." So we know we're to want God, but can we be trusted to want anything else? And what do we do with our human desires that sort of simmer below the surface of our lives? The desire for marriage, and career ambitions, the desire for children, the desire for home. Do these fit into our life of faith? Or are they just necessary distractions from what is meant to be our single-minded desire for God?

And those are the questions that I've really wrestled with in my own life of faith. Can I be trusted to want?

I have a little analogy that's very silly, but I think can make some sense and even just give shape to the question, “Can we be trusted to want?” As many of you know, Halloween has just passed, which means that candy is in the house. And I have five children, which means there's a lot of candy in the house. And actually, one of the things that we do after Halloween is, we sort through the candy and I let all of the kids pick out thirty pieces for the month of November. They can also pick out seven pieces that I will return to them in their Christmas stocking. So they don't get very much candy. The rest we actually put back into bags, and we take them to the school to donate because our children's school collects the leftover Halloween candy and gives it away.

So if you can imagine, Halloween this year was on Friday. We did all of our sorting. Monday came around and my daughter forgot to take the Halloween bags of candy. Tuesday came around and my daughter forgot to take the leftover Halloween candy to school. Can I be trusted to work alone at home with two bags of leftover Halloween candy? Of course I can't!

I think that is an analogy to, “Can we be trusted to want?” We're hesitant about desire. It sort of represents what's more uncontrolled, untamed about who we are. We have verses in the Scripture, like Jeremiah 17:9, "The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately sick." We've got stories like the parable of the rich young ruler who seemed so eager to follow Christ, but was unwilling to sell his possessions. Can we be trusted to want? And how does the Gospel answer that question?

The second part is where I want to go today, not only can we be trusted to want, but how does the Gospel answer that question? I think for the purposes of my book and the work that I've been doing on desire, I've settled on two main ideas about desire: That we are what we love, and that desire is central to who we are as human beings. And to assume that is to say something very particular about the process of discipleship, that discipleship is the formation of desire, of holy desire — desire for God, desire for his kingdom coming. And I want to say to you that if you're interested in this subject, you definitely need to check out James K.A. Smith's book, two books actually: Desiring the Kingdom and Imagining the Kingdom. And anything that I'm going to say or most of what I've written has really been with Jamie Smith's ideas in mind. And he says this, too, that desire is central to who we are as human beings and that central to the task of discipleship is the formation of desire.

But those aren't the prevailing ideas about who we are as humans and what is central to the task of discipleship. Because more often than not, we've been taught that we are what we know, and that the formation of knowledge is at the heart of Christian discipleship; which makes us really hesitant about desire. And just as a really quick example of this, this suspicion that we have about desire, I want to tell you about a book that I was recently reviewing for Christianity Today. It's a book on the Holy Spirit. I'm not going to tell you what the name of it is. You can probably figure it out if you really want to look it up. Because my main point in telling you this story is that I don't disagree with the book and I don't disagree with the premise of the author, the central premise of the book, I should say.

But I did have a dispute with him on this one particular point in the book. The book is on the Holy Spirit and the book is at the beginning talking about how we surrender our lives to the power and the leading of the Holy Spirit. This author was relaying the story of when he was choosing a vocation. He entered into university thinking that he wanted to have a career in law. And he was doing a Bible study on the book of Romans, though, and he started to started actually to have desires for ministry. And he thought about the unreached people groups in the world and realized, this is central to who God is, reaching the nations with the Gospel, and my heart's desires are leaning in this way. And so I don't think I should go into law. I think I should go into ministry.

I think that's a wonderful decision. My dispute wasn't with his decision as much as the suggested process of making the decision.

Let me tell you what he says in the book, and this is a direct quote. He’s giving advice to each of us as we seek the power and the leading of the Holy Spirit in our lives, specifically for life decisions. He says, "Write out all the things that you wanted from life. Finally, draw a cross over it as a symbol that you are offering it in sacrifice to God, saying, 'Not my will but yours be done.'" So the process then is, you need to make your list, all the desires, all the ambitions, all the longings, all the dreams. And then you need to put a big cross over that list, and then you need to crumple it up, throw it away, and start again.

And that is for me a very troubled process, because the implication of that suggestion is that desire and ambition have no part — they don't belong in the life of faith. And I disagree. Because as you remember, what I've said is that desire is central to who we are as human beings. And the formation of desire is central to the task of discipleship. So let me just make this case for you, very quickly. I can't take you through the entire Scriptures, obviously, in the course of this phone call. But I'm going to take you into one particular book, to answer the question, "Is desire dangerous?" "Can we be trusted to want?" "Should we have this suspicion about desire?" "Does desire not belong in the life of faith?" All these questions that have sort of simmered for me in my own life of faith.

So if you go into the epistle of James, what you see in the first chapter is that there's a desire problem. Well, what you see in the book is that there's a desire problem for the readers of the epistle of James. In the first chapter, James is talking about the nature of temptation, because there may be something that these people have misunderstood about temptation. They think that God tempts them. And James wants to clear that up and say, "No, it's not God who tempts you; it's actually that you're led by your own desires into temptation and then into sin." I'm coming to this is in the first chapter of James, verses 14-15. "Each person is tempted when he is lured and enticed by his own desire. Then desire, when it has conceived, gives birth to sin. And sin, when it is fully grown, gives birth to death," or "brings forth death." So immediately, we have a caution: a caution about desire, that there is this trajectory that desire can take. That we're tempted by our desires, that desires conceived can give birth to sin, and sin can bring forth death.

But if we turn over a couple of chapters to chapter 4, verses 1-4, James talks again about desire. And this time, it's in the context of their quarreling. There seems to be a lot of hostility among the people that he's writing to. And what he says is that the reason why you're fighting so much, the problem is, at the root of that, is desire — a problem with desire. And let me talk you through that a little bit. Here's what he says at the beginning of chapter 4: "What causes quarrels and what causes fights among you? Is it not this? That your passions are at war within you? You desire and do not have because you do not ask. You ask, and do not receive, because you ask wrongly, to spend it on your passions. You adulterous people! Do you not know that friendship with the world is enmity with God?"

The interesting thing for me here is that nowhere in the passage does James say, you know what? The trouble is that you wanted. The problem was your desire. He actually never says that it’s a problem with the fact that you did desire, that you submitted to the act of wanting. He doesn't say, "Stop wanting." And so that doesn't suggest to us that desire in and of itself is the problem.

The problem for these readers is that they have wanted in wrong ways, and so they didn't ask in prayer. They just started fighting among themselves. And they wanted for wrong things. And James is talking about what was ultimately adulterous and idolatrous about their desires. But what he suggests, though, is that it's entirely appropriate to pray our desires, and that there are even things we don't have from God because we have not prayed for them. I want us to see, even just very briefly from this passage in James, that the Bible is issuing both a caution and call when it comes to desire. And we are not telling the whole Biblical truth about desire, unless we have both caution and call.

Currently, I think we have a lot of caution. And the example that I told you from that book on the Holy Spirit was obviously an example of caution, that you write down all of your desires, your ambitions, you draw a cross over all of them, you crumple up the paper, and you say, "Not my will, but yours be done." We have that caution. And often it's very appropriate.

But what I also want to say is that the Bible issues a call to desire. And this is fundamentally something that I think is really important, and something that is important for us in terms of our own spiritual formation, transformation and understanding of the Gospel — that something is fundamentally lost when we do not invite ourselves to examine, explore, and participate in desire in our lives.

And let me briefly tell you what I mean by that. What is lost? That's the question. What is lost when we don't allow ourselves to want, or even explore wanting in a life of faith?

Well, first of all, our prayer life suffers. Prayer suffers if we exclude desire from our language, from our own self-understanding. Psalm 38:9 says, "O Lord, all my longing is before you. My sighing is not hidden from you." I think the Psalms in particular invite us to pray the range of our human desires and disappointments; our doubts, our longings; and there's something that the Psalms are trying to say to us that when we do this, when we articulate the most honest parts of ourselves, that we gain intimacy with God; and that when we don't, when we don't tell God the things that we want, or the ways that we are disappointed, or what we doubt, that we're actually holding him at arm's length.

We're really saying, you know what, if our heart is a house, we're closing lots of different doors and saying, "Yeah, let's not go into that room," or "We don't really need to sit on that furniture." But we do! Because the entire house needs to be open to God. And one example of just how honest articulation and prayer — whether it's desire, disappointment, doubt, longing, whatever it is — moves us towards intimacy and transformation, is in Psalm 73. And if you know this Psalm, it's basically the Psalmist who looks at the wicked and says, "Wow, look at them. Their life is so easy." And then he says, "What am I doing?" You know, "What good is it for me to keep God's law?" And he talks about how his foot almost slipped, and he didn't understand what God's purposes were in the world. Why did it look as if the evil and the wicked were prospering, and the righteous were suffering?

And the articulation in that prayer is not pretty. In fact, in verse 22 he says, "I was brutish and ignorant. I was like a beast towards you." And you get this sense that his honest prayer to God is just really messy and muddled, and confused and perplexed. He doesn't know what's going on. But when he does address God honestly, there's a resolution, he talks about, "When I went into the sanctuary of God, then I discerned their end." And I want to suggest to us that just praying desire, and with that disappointment, we move into greater intimacy with God.

And we do move into transformation. We see this in a variety of Psalms. I'm talking about Psalm 73, but I think we can find a lot of different Psalms that show us this pattern. And I don't want to say that this is just authenticity for authenticity's sake, because we have a lot of that in the culture. I think about Lena Dunham's new memoir that’s just come out, Not That Kind of Girl. And everybody's sort of up in arms — well, some people love her honesty and some people wonder why we have to be so confessional in today's culture.

I'm not saying that we need authenticity for authenticity's sake. But I do want to say that this kind of honest articulation and prayer is exactly like, if we look at Psalm 51, for example, where the Psalmist says that "You delight in the truth in the inward being, and the wisdom of the secret place." I think desire resides there. I think the inward being, that somehow we need to go there, if we are to find wisdom in the secret place. And it's not self-interested as authenticity is. So often people are authentic just because they want to get something for themselves. And it's not that; it's an authenticity that's really hopeful of change, that Lord, you know, this is who I am, and this is where I am, and that is my honest confession, honestly it is, it's very often confession. Until I admit it to myself and bring it into the presence of God, I think I'm still at an impasse. I think I'm still obstructing, in some respect, my own transformation.

Then there's one final thing that I want to suggest about desire in the context of prayer and what happens there. Actually I don't think it's my final thing, but here's another thing, that for instance, in Psalm 73, what's happening is not only that he is being honest and articulating where he really is and what his real desires are, like that his desire is just to give up. But there's a theological awareness that's going on, hand in hand with the, articulation of desire. I think if we want to reside in that tension, that there's this huge caution of desire and also a call to desire, that I think we can moderate desire by maintaining a theological awareness, like, "Who is God?" "What are his purposes in the world?"

I can ask God for the things that I want while yet recognizing that he's wise and that he's good, and that he's faithful, and that he's loving. Another example for me where to talk about the potential for prayer that's really honest with human desire, is the Lord's Prayer. That's sort of the focus of my book, Teach Us to Want. And it's always very interesting to me that the Lord's Prayer isn't just this holy, sanctified heavenly desire. It's not only that. It begins there, and that's super important for us, that the Lord's prayer doesn't begin with "Give us this day our daily bread." That comes later. But it doesn't exclude that, either, that while we yet begin praying, "Your kingdom come, your will be done on earth as it is in heaven," we orient ourselves to the desires that God has for the world, we are yet invited to pray our desires, "Give us this day our daily bread, forgive us our sins as we forgive, lead us not into temptation." As we pray our desires, we're actually moving toward participation with God.

I love (I actually just recently reviewed) Tim Keller's newest book on prayer — which was excellent and I highly recommend — for Christianity Today. And one thing that he suggests about prayer, or praying our desires, he says, "When we pray our desires, we ask what we ourselves might need to do to implement answers to our prayers." There's some way that desire expressed in prayer is connecting us with the mission of God, that Abraham's desire for Sodom and Gomorrah is part of his participation in God's mission. David's desire to build the temple, Paul's ambition to preach the Gospel in unknown lands, that desire and ambition can be given to us by God and can be glorifying to God. So that's sort of a Biblical case for desire.

Do I think that we need to be cautious about desire? We do. And just like in the epistle of James, we're very often an adulterous people. And yet there's a call to desire because it leads us into intimacy with God, into transformation and also into participation with God's mission.

I just want to end with a little story that has proved to be really prophetic in my own life. When I started to write the book, Teach Us to Want, I actually had — as I'm doing now for book number two — taken a week away from my family, and I was on a writing retreat. I met a woman there connected with this retreat center who prayed for me. And the details are unimportant, really, for the purpose of the story. But anyway, I didn't know her. She didn't know what I was writing about. She knew nothing about me. We had talked for about two minutes before she actually put her hands on my head and prayed for me. And this is what she said; this is how her prayer opened: "Father, your desire is for us. You want to be with us, and it is not difficult."

I just want to end with a little story that has proved to be really prophetic in my own life. When I started to write the book, Teach Us to Want, I actually had — as I'm doing now for book number two — taken a week away from my family, and I was on a writing retreat. I met a woman there connected with this retreat center who prayed for me. And the details are unimportant, really, for the purpose of the story. But anyway, I didn't know her. She didn't know what I was writing about. She knew nothing about me. We had talked for about two minutes before she actually put her hands on my head and prayed for me. And this is what she said; this is how her prayer opened: "Father, your desire is for us. You want to be with us, and it is not difficult."

And that reminds me that what the Gospel has to say about desire, can I be trusted to want? Left to myself, no. There are many things that I would want wrongly in wrong ways, and that when I go and start examining my desires, I do put a finger on a lot of my own contradictions. But that God's desire is for me. And the Gospel is making me new. And to return to even my opening analogy about the Halloween candy, which was so silly, it's really silly. But it reminds me of this; that I can become the kind of person to handle two leftover bags of Halloween candy. I can become the kind of person, through the indwelling power of the Holy Spirit, to handle what's potentially good and often dangerous about desire; that I'm transformed, not just at the level of my belief.

The Gospel isn't just about remaking my behavior, but he, Jesus Christ, is actually reforming me at the level of desire. I think there's a lot of potential in that. I think there's potential for us to find intimacy with God, and ultimately I think there's potential for us to also identify our own particular callings through the exploration of desire.

Thanks so much for listening.

Questions from the audience

Joanne: Thank you so much, Jen. I have a few questions that have come in. First question says: I'm in a difficult season of marriage that I never expected. It seems like we are unaligned in many ways. My husband no longer identifies as a Christian, and he no longer thinks he wants to have kids. I have hope and I've been praying, but it's still difficult. How do I deal with the desires, spouse's relationship with Jesus, children that seem good and were possible at one time but no longer are sure things? How do I handle having these deep desires and longings when they are a real uncertainty that they might not come to be?

Jen: Yes. That is exactly where desire brings us. It brings us right to the threshold of disappointment so often, because there are good things that we can want, and there are good things that will be withheld from us. And I think that is a reality of the world that we live in. I think that the Garden of Gethsemane reminds me that desire and surrender can coexist; that we can pray, "Lord, take this cup from me, please, please, do that. Lord, this is what I want. I want my husband to want children. I want my husband to follow you. I want to have a family that glorifies you." I mean, these are good desires, and I think they're desires that should be pursued in prayer. And coexisting right alongside that is surrender: "Not my will but yours," "What do you have for me here?" "Help me to learn, to obey, to trust, to wait, to anticipate." So I know that's not really an answer; it's only to say that I think that we often give up too quickly on desire, and there's so much to be said for persistent prayer in the Scripture, that for example, the widow who Jesus' commends, who goes to the judge day after day, and he's not just. But because she keeps bothering him, he finally gives her justice.

And this is a parable to teach us to pray. I think it's also — and I think prayer inspired by desire, should be that kind of persistent longing that we bring to God — especially when we are convinced that the things that we want are good. And until we hear a clear word from God that, "No, don't pray this anymore," like Paul had from Jesus. You know, "Take this thorn from me; take it from me, take it from me." Three times he prayed, and finally Jesus said, "It's not going to happen. But my grace is sufficient for you." So, I just want to encourage this woman to pray persistently, to be in community where those desires are also being affirmed and upheld by other women of faith. And yet to listen to the Holy Spirit, and receive the grace that's sufficient for her.

Joanne: Amen. The next question that came in says, "What if we have brought our desires to God in prayer many times, and all we hear from him is silence or, at best, a reminder that Jesus suffered and that the unfulfilled desires as well? I'm still left in the pain of unfulfilled desire.

Jen: Yes. I was reading Hebrews today, and reminded of, all that God said that it seemed fitting to make Jesus our Savior through suffering. And I'm paraphrasing. It seemed fitting. And I thought, well, what seems fitting about that? Suffering seems terrible and awful, and we always wish that we could be spared it. And I think that's our longing for Heaven. I think our disappointed desires are pointing us toward a greater reality, and if you're like me, you have a hard time of conceiving of Heaven, of longing for it, especially when life is good. But when we suffer, when we're disappointed, when things are withheld from us and life feels just not right, and we don't feel at home in this earth. We are longing. We're the people who are longing for a better homeland.

And I know again that's not an easy answer. I think that we have to walk with people in faith, who just keep reminding us of God's goodness and of God's grace. And that's one thing I say in the book. I have to say that if there's one chapter that I think is most important in the book, it's the chapter on suffering. I talk about my own loss of my father when I was a freshman in university, and then the suicide of my brother my first year out of university, and this reality that we have, somehow, by faith, we're learning that God is good when life is not. And I know that's not easy; I think we're spending the rest of our lives trusting that God is good, even when life isn't.

Joanne: The next question that came in is, can you comment a bit on ambition? The talents of balance expected of women in the faith of wanting something more than of a career, when I feel lost to learn healthy ambition since it was never a part of my upbringing?

Jen: That is an excellent question, and it's interesting because when IVP said that they wanted to put ambition in my subtitle, I was like, "No! We can't do that!" Because ambition feels so, it's so negative. We at least have a negative connotation to it, especially with women. And then you put Christian women on top of that.

I think that the Bible is full of ambition, and I can't think of anything more ambitious than the Lord's prayer, that if you pray "Your kingdom come and your will be done," I mean that — there's just no greater ambition, wider, broader, crazier ambition than that for the kingdom of God to be coming on earth. I think what we need to do, and this is true of all desire, I think what we're trying to when we enter into desire or explore and examine it, we're trying to see the cultural corruption. We're trying to understand, what does culture — how has culture, oriented me in a way that's wrong, that's disordered?

And one such way is not just that desire, that culture influences us toward selfish ambition. But could it also be that culture influences Christian women to want too little, and to be ambitious for too little? And I think that's true; I think even in just my study for my second book, I'm realizing, there's a whole history behind obviously women's roles and men's roles. And I think we're obviously always with desire and with ambition trying to understand, what is culture telling us? And what is God through the authority of the Scripture telling us, and parsing it out in that way? Great question, though.

Joanne: Yes. I agree. There is a tension of us not wanting too much and not having ambition. This is actually a related question, I think. In the book, you raise a discussion — you discuss a secular culture attached to the unqualified goodness of desire. How different for us, as Christians, how do we develop a sanctified desire?

Jen: A sanctified desire. Yes, well, I think if you go back to those two words, caution and call, the culture is all call and no caution. You know, that desire, I mean it's awesome and you should always follow it and whatever you want is good, and you're entitled to that. And I mean desire actually just is sort of the moral category, the operating moral category, right? Like, if you want it that makes it good; that somehow you would be denying your own particular design to refuse something that you want. So how do we pursue sanctified desire?

Well, we need the caution as well. I mean, we do need to understand as human beings that, especially in the culture in which we live, how often, how lured and tempted we are towards selfish ambition, towards vain conceit, toward the pleasures of luxury and convenience and ease and that what is not intuitive to us, as human beings, is the self-sacrificing love of Jesus Christ. Like, that's not our ambition; that's not naturally going to be our ambition.

But we have to trust, though, that the process of the Gospel is about conforming us into the kind of people where that becomes our intuitive language of ambition and of desire. And so, to remind us of that example where you're just supposed to write everything down, put the cross over it, and crumple it up and throw it away, I think we need a better process. I think we need to say, "Well, what's on that piece of paper? What in that is disordered about those desires and ambitions?" "What is really just vain glory making a name for myself?" "But what could actually be good and God-given about that list?" And so I think we need a better process of discernment. I don't think we need to throw the baby out with the bathwater, I guess.

Joanne: I agree. I think that there is something about what it means to be in community with others to help us also begin that process, too. What particular insights do you have for women who too easily walk away from their desires and dreams?

Jen: The first, I think is that you absolutely have to introduce this question into your prayer life: What do I want? What do I want? I think we really hold that question at arms' length with God and also with other people. I think we just have to engage that question in prayer and also in our communities. I think it's a scary question because like I said, it's sort of going right towards your own contradictions. I mean, if you're going to talk about what you want, you'd better be ready to start openly admitting and confessing your sin.

But I think there's just a ton of potential in that question. Like, for instance, I have been on staff with my church just for just a little over a year. I took the position as a very (I was thinking) kind of short-term stop-gap measure for them. There was a need, and I knew I could fill it. And I took it after I wrote the manuscript of Teach Us to Want. And I knew that there would be a lull, and you know, it was great. It was wonderful, and I have to say that I love serving the local church, but I knew also that I couldn't do both. I couldn't write and also serve on staff at my church. I just don't have enough time and also be able to be present to my family.

But of course, every time I would bring this up to the pastoral staff that, you know, I didn't think that I was going to continue long-term, they'd always think of these alternative ideas, like, "Okay, well maybe you could do this, or maybe you could do that, or maybe we could rearrange it in this way." And they really, really wanted to keep me on. And I think you can feel guilty when people want you to do certain things. And you know that it's a good thing, you're fulfilling a need.

Those conversations were happening over the course of several months, and then over this last summer I was doing the Bible study, Teach Us to Want (there's an accompanying Bible study) and it was a group of women from my church. And I was really asking myself, "Am I praying What do I want? Am I recognizing that in prayer?" And I was just talking to the Lord with that, about that, "You know Lord, what do I want?" And immediately I thought, "I don't want to serve on staff at church." And it wasn't because I didn't like it; it was just because I just really didn't feel like I had the time. And I felt a great freedom from the Holy Spirit to say, "You don't have to; no one's making you." And so I quit. And it was really freeing. I think my pastors understood, and actually celebrate my call to writing. So I think I could've stayed on the hook of obligation for quite some time. But just asking the question What do I want? allowed me to explore it, examine it, and then realize with the Holy Spirit that I had the freedom to choose.

Joanne: So in the follow-up question, I now say this as for me, growing up to want was not the faith, right? So how do you discover what you want? I mean, in the midst of that, how do you have some self-discovery of wanting? Of the wants you have — you really have?

Jen: That is tricky. I actually have a friend who has just read the book. And she was like, "I just don't know what I want." And I do think there are people that live more acutely aware of their desires and there are other people that live less acutely aware of their desires. But I think maybe — maybe people aren't ready for the question, "What do I want?" But I think we're all aware of the kinds of things that we do. We're aware of the habits that sort of constitute the whole of our lives. And maybe it's just starting there, because actually, James K.A. Smith talks in his book about how desire is formed by habit, and so maybe taking it a step back and saying, "Now what are the things that I regularly do?" And those actually can reveal something about what you want.

Unless you're really, really good about doing things you don't want to do, which some of us are. But a lot of us very naturally just do the things that we do want to do. That's not going to be true for everybody.

There's another way of looking at it. Get involved in community conversations about desire, having other people tell you, reflect back to you I see that this is what you seem really passionate about, or these seem to be the things that stir you or animate you, or this is what I hear you talking about, or these seem like the central values of your life. Having other people comment on that. I'm not sure if that helps.

But you're right, for some people, they're just not naturally self-reflective, so it can feel confusing, how to do that. Feel free to pursue it with a licensed counselor or spiritual director, as well. I think having somebody who's really gifted in drawing you out can be really helpful.

Joanne: Thank you. A question I'm also having to think about: do you find that desires and wants begin to, in women, change in stages of life? Or is it something that you find what you want when you're younger is it preparing you for what you want later in life? How would you describe it?

Jen: I do find — well I guess I can only speak for my own experience. I'm forty, so I have felt that there are some desires that have been very residual, and other desires that have changed. And I think what's been residual about my own desires is, you know, even from a very young age, I felt called into some kind of ministry. I didn't know what that was going to look like. And I didn't really pursue it vocationally, which sounds strange. But I always thought, "I want to be involved in leading Bible studies." I always had a desire to write. And I did that in a lot of different ways, even in my teens and into my twenties. So that's been very residual, like, here I am at forty, and the Lord is giving me opportunities to do the things that I wanted, even at twenty. And that is a grace in my life, and I'm really thankful for that.

One thing I think that's shifted, though, is just the nature of my ambitions. I think that I’m more satisfied now to lead a slower and smaller life. I think if that's what the Lord chooses to give, I don't find myself wanting as maybe I once did, and maybe I didn't even realize it then. But you know, I used to think that I wanted a certain kind of ministry that was more visible, or broader, or I don't know. And I'm sure there was a lot of selfish ambition involved in that. But now I feel like, "You know God, I am very happy to be faithful to the opportunities that you give me. I want to be as ambitious as you want me to be. But I'm okay with that if that looks different." And that was even just telling an editor at IVP, I'm very happy to spend more time, rather than less, in building, whatever God has, you know, whatever my participation is in the kingdom, I'm okay with that taking a while. And I also feel like I'm happy to do things very local and small and invisible, that people never see publicly, who don't know me. I mean, you know, people beyond my own neighborhood wouldn't know. I'm happier to do that than maybe I was twenty years ago.

Joanne: Questions are coming in, but I just wondered as you hear all these questions, and as you've presented, is there anything else you feel like, "I really want to add this to the conversation and the presentation"?

Jen: You know, I'm not sure. I feel like I've talked a lot. I'm thankful to be talking about this, because I think our natural tendency is just to incriminate our desires. And I guess one thing I could say, is just even with the book, the book embodies that whole process of discovering desire. So for instance when we moved here three years ago, four years ago — here's another way actually, that I think you can discover desire in your life — is explore your resentments. And for me, we moved here for my husband's job. And I, underneath the surface, was thinking, "My whole life is going to be like this. I'm just going to be following him around, whatever job he takes. And all my own desires, callings, pursuits, will be secondary." And I felt resentful about that, to be quite honest.

And we had a long talk — I will say an animated discussion — about that, many different discussions. And he said, "What do you want? What do you want that I'm not allowing you to do or that our life isn't allowing you to do?" And when he asked me that, and just through prayer, I started to realize, I really do want to write. I want to write. And when I came to that conclusion, I realized, he wasn't stopping me. There was actually nothing stopping me. And that's when I began to write.

God opened up all these opportunities, one after one, so that it eventually became a book. But what if I'd never asked, what if I'd never explored that question, what do I want? And what if I'd never stepped into the risk? I think that maybe I'll just end here, that right on the heels of desire is risk and responsibility. That's how I've found it in my own life, and that's maybe another reason why we avoid it. We're afraid of the risk, and we don't want to shoulder the responsibility for the desires that lead us into participation and mission. There's so much good, and it's so beautiful. It's a way to experience God's grace in your life, that you can want something and that it can want you. And that you can enter into that beautiful dance of grace, and grow in your intimacy with the Lord.